I asked Kate to marry me at 11:59 PM on December 31, 1998, on the sidewalk outside the Flatiron Building at 23rd and Park in New York City. (She said yes.) Earlier that night we had seen They Might Be Giants: they booked two shows at Tramps that night, and we went to the early one.

TMBG was a fave of Kate’s from before I met her in our freshman year at college. My great friend and wunderkind tastemaker Bob was into them back in high school; I just hadn’t caught the bug. I fell for Kate and The Two Johns hard, and at around the same time. So of course it made perfect sense that she and I caught a They Might Be Giants gig on the very day we agreed to get hitched. In a way, it closed a loop, and we had taken a long way around that loop in the preceding three years.

When we graduated from college in 1995, Kate moved to Cambridge, and I moved to New York. The fall of that year nearly broke me—well, maybe not nearly, but it was definitely a low point. Within a seven-day period the Indians lost the World Series, Kate broke up with me, and I saw Gwyneth Paltrow’s head delivered to Brad Pitt in a box. I was starting to believe there were no happy endings.

I shouldn’t have to say that the breakup was the worst of these three misfortunes. Notice of it arrived on a weekday: I had gone home from work during my lunch hour and received the Dear John letter in the mail.

I remember shortly afterward I was standing at the counter of a McDonald’s, on I think 86th Street, in a haze. There was a promotion that day: two Big Macs for a dollar. I didn’t want two Big Macs. I had no need for two Big Macs, because I was single on that day, as I was likely to be forever. Nevertheless, the girl at the counter laid out the logic for me in her New York accent, which on any other day wouldn’t have made me feel so completely like an alien, too far from home, and alone:

As between two Big Macs for a dollar and one Big Mac for four dollars, you gotta take the two, right?

“Sure. Whatever,” I said, with tears filling my eyes.

You gotta take the two, she repeated, half under her breath, as if she needed convincing, too. When the burgers came, I tried to hand back one of them.

“I don’t want it,” I said.

You have to take it.

“I can’t eat it. Give it to somebody who’s hungry.”

You have to take it.

This went round and round for some time, before I conceded the point, like I always did in those days—and still do most of the time even now. Broken and powerless, I couldn’t even refuse a free burger.

Back at work and eating at my desk. One of the attorneys I worked for appeared in the doorframe of my office. “Are you okay?” he asked. This was embarrassing. Let’s see if I can make it even more so:

“Kate broke up with me,” I blurted out, pressing the base of my left palm into my eye.

That had Craig on his back foot. Oh,” he said. Long pause. “Can I have some fries?”

“I have this extra burger,” I told him.

“Nah, I just wanted some fries.” And he left.

The winter was long. I worked long hours to make rent and had very little money to spend to “enjoy the City,” as family and friends urged me to do. On Friday nights I would take the train down to Times Square to the Virgin Megastore. They had a bank of, I dunno, twenty CD players mounted on the side wall with headphones jacked into them. Each player had a different album loaded into it. I’d spend two, three hours there listening to music, and if I had cash in my pocket I’d bring home one or two CDs. Now and again a band I liked would come through, and I’d head on down to the Mercury Lounge, or the Wetlands, by myself.

The thing is, I didn’t concede the point. Not with Kate. I called her from time to time, friend to friend, to see how she was. Didn’t tell her I was hurt, didn’t tell her I was fine. I just kept myself in view. And by the time the spring thaw came, for reasons I can’t discern and that she never explained, she had changed her mind and wanted me back.

So began the Peter Pan and Occasionally Greyhound Era, wherein Kate and I took turns riding the bus between Boston and New York, New York and Boston, every three to six weeks. My outbound trips to see her in Cambridge resulted in:

Many hours stuck in standstill traffic on I-95;

Many Friday night dinners taken at the Roy Rogers just off I-84 over the Massachusetts border, where the Peter Pan drivers stopped for their break; and

Many late Sunday-night disembarkations in the Port Authority bus terminal, where on the short walk down from your gate to Eighth Avenue you were likely to witness manifestations of at least five of the Deadly Sins (but no heads in boxes, thank God).

The flipside weekends, when Kate rode the bus in to see me, were magical, and not just because I didn’t have to do the traveling. We ordered in Fresco Tortilla, the Chinese-owned Mexican chain. We had deli sandwiches at Katz’s, sang Dean Martin tunes at La Mela on Mulberry Street, sipped frozen hot chocolates at Serendipity. We checked out art films at the Angelika Theater, and if I’d saved up enough, we might even take in a Broadway show. More than anything, though, we walked, for miles and miles, up and down Fifth Avenue, over the Brooklyn Bridge, through Union Square and Gramercy Park, into the West Village. Walking, like dreaming, is free.

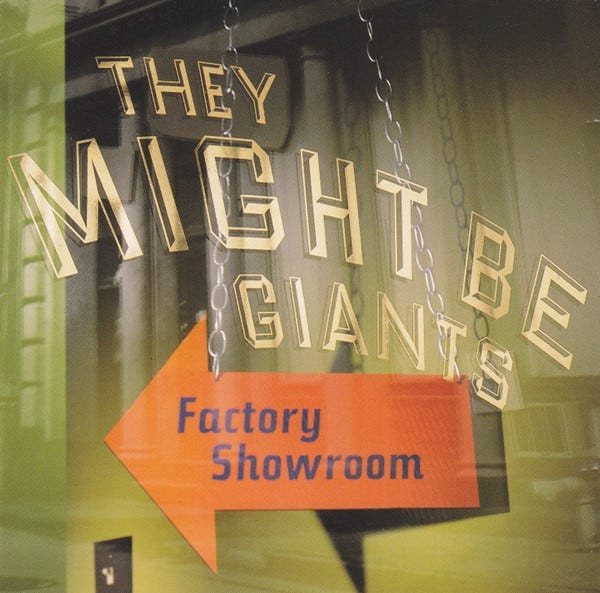

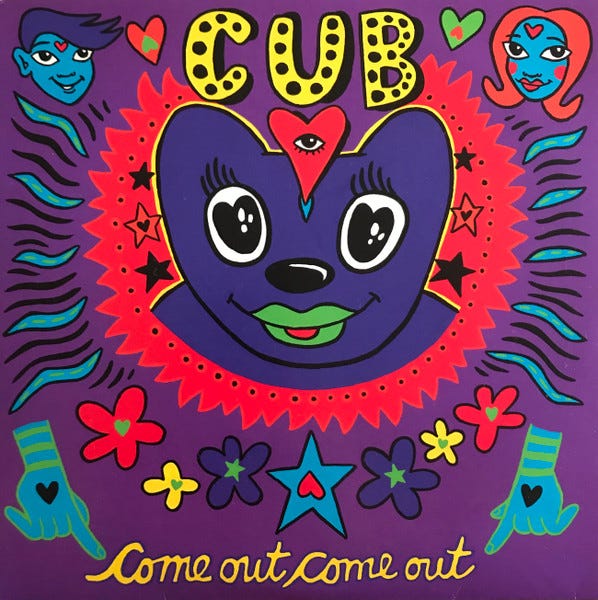

Factory Showroom, They Might Be Giants’ sixth studio album, came out in 1996—i.e., right around the time Kate and I reupped. Track 6 on that record is “New York City” (Apple Music, Spotify). It’s actually a cover of a song by Cub (Apple Music, Spotify), an all-girl pop-punk band from Vancouver—so one of the Johns (Flansburgh, I think) revealed to us at one of TMBG’s shows. If you want to know what Cub was about, and how delightful they were, check out this video for their version of “New York City.” It’s a perfect pop song about falling and being in love in the City. The chorus is not at all subtle, but lovely, and when I think of my three years living in Manhattan, it’s 100% on-point and spot-on:

’Cause everyone’s your friend in New York City,

And everything is beautiful, when you’re young and pretty.

The streets are paved with diamonds, and there’s just so much to see.

But the best thing about New York City is … you and me.

When we were planning the wedding, I cornered the DJ and pressed him about the songs he expected to play at the reception. He caught on quickly, and with albeit some misgivings about what could happen on his dance floor if he ceded full control over the set list to the groom, he did allow me to submit a good dozen or more advance requests.

“New York City” was of course on that short list.

Ten years later I was singing that song to my kids before bed. Sometimes the Cub version, sometimes the TMBG version—the lyrics differ in some spots: “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” versus “Katz’s & Tiffany’s,” “the Empire State where [Dylan or King Kong] lives,” depending on which band was in charge. There was a period of a couple weeks when I’d be in my three-year-old daughter’s room singing her the song, and my four-year-old son would lurk in the hall until the end of the third verse. Then it would get to the end, and he would burst into his sister’s room, skidding across the floor in his footie-pajamas, to sing alongside us, at the top of his lungs:

I’M THREE DAYS FROM NEW YORK CITY AND I’M THREE DAYS FROM YOU.

And onto the chorus we’d go.

Lady Miss Cleo on the public access channel, that sub shop at 93rd and 3rd, Hitchcock movies in Bryant Park, the shattered window on the 6 train, Papaya King, concert listings in the Voice, talking Greedo language over a cabbie’s CB. So much to remember from my three years living in New York—some of it still there, and a lot of it long gone.

But the best thing about New York City was always Kate and me.

This was a fantastic read!