From an early age, I’ve always loved the Classical antiquities. My favorite book was for many years, and might still be, D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths (Amazon), a folio-sized anthology about the Olympic Gods and their half-mortal hero children. As a tween I used to draw free-hand maps of Greece. For fun.

Between second and eighth grade I went to a private elementary school operated out of a banged-up old mansion in downtown Youngstown. Imagine Hogwarts smooshed into a 3700-square-foot house, after the climactic battle destroyed it. Or maybe more spot-on: the sort of school building Roald Dahl or Lemony Snicket would dream up to inflict on Matilda or the Baudelaire children. The halls were dark and lined with shelves displaying the skulls of various apes and early hominids—some plastic, others real—and biological specimens in jars. The air was musty: red, yellow, and green mold grew on our composition books over the summers, and the cleaners washed the floors with a vinegar solution you could smell through much of the day. The plumbing was old and something made the water olive green, at least for the first ten seconds after you turned on the taps. But if you waited long enough, it resolved into a clear and borderline drinkable liquid. Sort of a water-plus.

The Kennedy School was cool as shit.

The school followed a Classical education model that chucked out boring-as-hell American History in favor of the study of ancient civilizations. We started with Egypt, then covered Mesopotamia, Bronze Age and Classical Greece, and finally Ancient Rome. We read excerpts of Herodotus’s Persian Wars, and in the hallway outside my Upper School classroom, just beside a scaled-down replica of the Rosetta Stone, was parked a student-made project rendering the Battle of Thermopylae in clay, with plastic ships and soldiers.

You’re wondering what any of this has to do with Eurythmics. Bear with me.

Another essential part of the Kennedy School curriculum was Art History. This came after lunch, which looking back may not have been the best idea. The lights would go out, Ms. Ciarniello would pull down the window shades, and she’d walk us through slide after slide after slide of artifacts that the school principal, Isabelle Kennedy Turner, had methodically photographed in museums on her overseas travels with her husband. There were hundreds of slides. Any sensible person would have fallen asleep at least once during these sessions, but I never did. I was all in for the cat mummies and potsherds and Linear A inscriptions. From the edge of my seat: next slide, please … show me more.

In a multiplicity of timelines not so far removed from this one, I’m an archaeologist, or at least an antiquarian. The notion that we might live among the relics of a forgotten, or at least not fully-pieced-together, past is crazy capital-R Romantic to me. Growing up in America was a real disappointment on this score. There are multiple levels of broken city resting under modern-day Rome. Back in 2016 we engaged a tour guide to take us through the Colosseum and Roman Forum and point out the sights, but by far the coolest stop on our tour was the San Clemente Basilica, a medieval church that had basement-level access to an earlier, 4th-century basilica, and below that the ruins of a Roman insula.

By contrast, what interesting artifacts could I find in Warren, Ohio? At some point when I was eleven or twelve I convinced myself that a mound of dirt alongside our driveway was an Indian burial site. I dug and dug and dug for at least twenty excruciating minutes, before my father got home from work and told me No, that’s just dirt piled up from when the builders dug out our basement.

So much for archaeology, then. The tracks and traces of ancestors that we might happen upon in the physical world are increasingly too few and far between, especially here in the New World. Contrast the business of the antiquarian, which isn’t so much to look and dig personally as to pick through the findings of others, follow leads, and piece together the mysteries of the past. There’s never been a better time to be an antiquarian, or a researcher of any kind. If the answers you’re after are not in a book, then Google can find them, and if Google can’t find them, we have generative AI platforms to make them up.

Uh … Eurythmics? Yes, getting there.

But there’s still more I want to say about my time at the Kennedy School. In the winter we would ice skate in Wick Park, on the flooded and frozen-over tennis courts across the street from the school. For want of an actual ball, we used to play soccer using a tucked-up shoe rubber, on the school driveway. Long stretches of game play involved multiple kids kicking the foot of the player who was stepping on the rubber. I recall one strange day when our teacher was out sick and Mrs. Turner gave us all copies of Death in Venice to read during class. Many confused looks were exchanged across the room that afternoon.

But let’s reel this back in a bit. One year the school arranged for our class to take weekly trips across town to the public library. At the start of the term we were given a list of, I don’t know, around twenty research assignments. Our task was to identify and use all available library resources—the card catalog, the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature, the reference desk, microfilm, microfiche—to access the information needed to complete each assignment. One of the assignments was to summarize and explain the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. Another was to find newspaper reporting from the last time Halley’s Comet passed by Earth.

(Now that I think of it, we must have been doing this work in the winter and spring of 1986, when the comet was on its way back into our night sky. For our joint Upper School art project that year, we reproduced segments of the Bayeux Tapestry commemorating William the Conqueror’s invasion of England in 1066. I was proud to be able to to do the stitching of Halley’s Comet, which appeared in the sky in that historic year, too, auguring victory for the Normans.)

The library project was daunting. It was a scavenger hunt, spread out over several months, and we only had an hour or two each week to work on it. At the start, I hated everything about it, because it required resourcefulness, which I wasn’t aware I had and certainly wasn’t in the practice of applying. To this point, I had learned what teachers taught me or what was written in books people had given me. I wasn’t in the practice of going out on my own seeking knowledge. But once we got into the groove with that project, it was fun as hell. The particular library skills we learned and applied would not be especially useful, going forward. Nobody needs the Reader’s Guide anymore. Far more important—and far cooler—was that this work gave me The Thrill of the Hunt.

So now let’s talk about music. I could tie this all together quickly and say when I first heard Eurythmics in 1983, I was a student at the Kennedy School. By day I was studying Greek mythology, and at night I sat wide-eyed in front of MTV, watching, among other things, a close-cropped Annie Lennox slam her fist into a boardroom table.

But that doesn’t quite get us to where we need to be, because this post isn’t about being a kid in elementary school. It’s about my thirst for discovery, and specifically for reaching back to find old things. And for that matter, “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” (Apple Music, Spotify) isn’t the song I picked.

I don’t listen to much new music anymore. There was certainly a time when I was out there, scraping and trawling, beating the streets in search of the Next Big Thing I could take back to my gang. Lately, though—and by lately I mean for the past maybe twenty-plus years—I am much more inclined to look backward.

Arriving on this Earth in 1973, and tuning in earnestly to rock music for the first time in the mid-1980s, is a bit like walking into a play just after intermission. From the jump you’re entertained. You take the culture as you find it, after all, when you’re young. A nine-year old sees fire-haired Annie Lennox in her power suit and says, Sure: why not? Likewise, in eighth grade I was firing up Organisation by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and was unfazed by the strangeness of the sounds I heard.

But I was never going to be completely satisfied with in-the-moment enjoyment of songs that landed in my lap. By the time I was in college, the part of me that craves complete information and an understanding of context began asking more and harder questions: Where did this come from? What came before this? What have I missed? And at that point the Classics student’s preoccupation with origins, old things, and bygone moments took hold, and I began my decades-long (and counting) research project into rock music.

These last few decades have been the Kennedy School library unit all over again—attacking the problem from multiple angles, none of which involve microfiche, thankfully. Some important source materials:

Hardbound books, including John Savage’s England’s Dreaming, The Great Rock Discography, Lester Bangs’ Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, The Rough Guide to Rock, Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, the 33⅓ series.

Reference sites like Allmusic.com, Discogs, and Wikipedia, at least once a day, for artist bios, discographies, credit and release information, and critical reviews.

The Internet Archive, principally to consult Julian Cope’s out-of-print Krautrocksampler, but also to download vintage early MTV video and the occasional live audio recording.

Films, scripted and documentary, including 24 Hour Party People, The Filth & the Fury, Moonage Daydream, Control, Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Underground, Conny Plank: The Potential of Noise, and It Might Get Loud.

Napster, for as long as it lasted.

Various podcasts and websites, including The Quietus; It’s Psychedelic, Baby; Pitchfork; Slicing Up Eyeballs; 1001 Album Club; and No Dogs in Space.

For each of the examples I gave, there are a dozen others that are just as useful and informative. And that’s not to mention the Apple and Spotify streaming services I link to in every one of these posts, where I can drop in at any time to actually play the music I’m finding. Or for that matter YouTube, which has all the songs Apple Music and Spotify haven’t in-licensed (I haven’t stumped it yet), more than a few documentaries that are out of distribution, hundreds of John Peel’s BBC radio sessions, and tens (hundreds?) of thousands of archival live performances and music videos to watch.

A most essential secondary source that deserves its own paragraph is Robert Dimery’s 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (Amazon), which sits on the desk in front of me as I type these words. The 1001 albums selected for this book are listed chronologically, and while I’m not close to having heard them all—I intend to live for a good long while after this—I’ve played a bunch of them, simply on the book’s recommendation. More than any other single source of information about music, Dimery’s book stitches together the long, spooling tapestry that is the rock music tradition. It shows how various influential artists propagate their ideas over the generations, how rock genres that seem fully distinct and sui generis actually relate to and derive from one another. Reading Dimery’s book and playing the records is a lot like excavating a vast archaeological site—let’s say the palace complex at Knossos—and slowly, over time, coming to appreciate how it all fits together.

It’s this exploration that is most rewarding for me. Putting in the work—chasing leads, pulling on threads, discerning patterns, finding and tracing recurring names and tropes, noting convergences—that’s the Thrill of the Hunt. And when the hunt is over and you’ve bagged some big game, the meal that follows is ever more delicious.

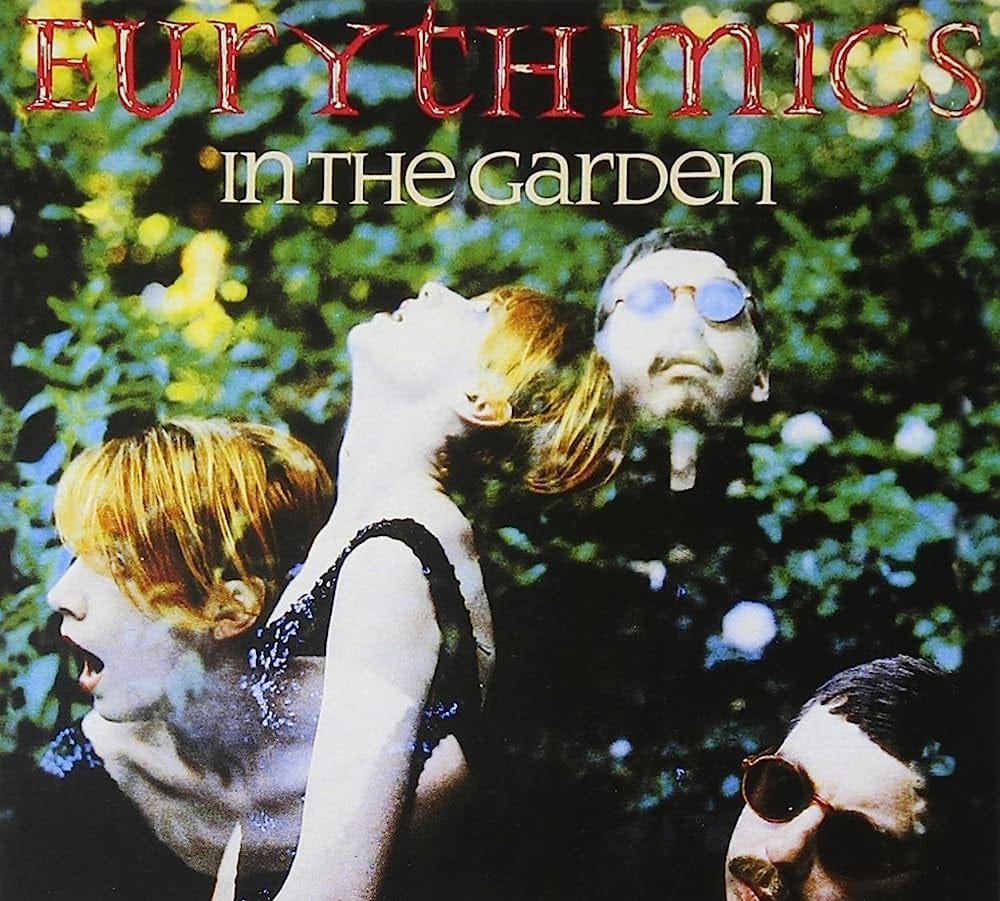

So, Eurythmics. I’ve known them for forty years. Liked a lot of their songs, never bought any of their records. But earlier this year, I was listening to 1001 Album Club’s episode on their 1982 Sweet Dreams record. 1001 Album Club (Apple Podcasts, Spotify) isn’t just a podcast—it’s a commitment. A handful of music lovers in Louisville, Kentucky have Dimery’s book and are listening to all 1001 records in order, recording a standalone episode for each album. In the Sweet Dreams episode, the podcasters noted that Eurythmics had recorded their first LP, In the Garden, at Conny Plank’s farm/ studio outside of Cologne.

I knew Conny Plank’s name from my recent deep-dive into Krautrock, the not perfectly PC genre term assigned years ago to the several bands that rose up from the ashes of post-war Germany to release some of the best psych rock and experimental electronic music of the late 1960s and 1970s. My friend Carla and I like this music so much we’ve started our own podcast about it (Apple Podcasts, Spotify). The podcast work entails even deeper research than I’m inclined to do ordinarily. But even a top-level survey of the available sources will tell you Conny Plank was a generationally gifted and committed sound engineer who produced such monumental German acts as Kraftwerk, Neu! (see “Neuschnee”), Cluster, Harmonia, Ash Ra Tempel, and Guru Guru. So yeah: I knew Conny Plank’s name.

I looked up In the Garden on Discogs, and not only did Plank produce it, but prominent Krautrock musicians like Can’s bassist, Holger Czukay, and drummer, Jaki Liebezeit, played on it. Yet another of my all-time favorite drummers, Clem Burke from Blondie, also did session work on this record. From here I went straight to Apple Music to hear what this convergence of early Eurythmics and Krautrock might sound like. I dialed it up in my car, and I immediately fell in love with the single, “Belinda” (Apple Music, Spotify), a rocker that sounds very little like the Eurythmics I knew from MTV.

It was then a matter of figuring out where I could buy this record on vinyl. Discogs showed that vintage copies were available on the cheap, if you lived in the U.K. or Europe. This record largely fell flat back in the day, and it barely made a dent in the States. But two weeks ago, I was in Chicago, and I did some record shopping. On Wednesday afternoon I walked to Shuga Records on North Milwaukee Avenue, six miles round trip through blistering heat, from my hotel on the lake. Absolutely worth it, because when I got there I found and bought a sealed copy of a 2018 remaster of In the Garden. Not the original article, and in this respect more like one of those plastic gorilla skulls at the Kennedy School. Or maybe an actual found skull, but carefully restored by museum experts. In any case, I got it.

The last track on Side A of In the Garden, playing this minute on my turntable, is “Your Time Will Come” (Apple Music, Spotify). It was parked right there on the streamers for years, but I didn’t really hear it until I brought the record home and spun it on the turntable. By any measure, it’s a deep cut—an album track by Eurythmics before they were Eurythmics: 16,972 hits on Spotify, compared to 376K for “Belinda” and 1.08 billion for “Sweet Dreams.” But it’s perfect. Plank’s production work is right on point, as expected. Jaki, Holger, and Markus Stockhausen (son of pioneering composer Karl) play brass instruments on the track. The synths and Annie’s vocals sound a ton like the music Stereolab would put out a decade later on Mars Audiac Quintet, so I have to think somebody was listening to and loving this record back in the day.

And now I am, too. What a find, and what fun searching! I think I’ll do just this sort of thing for the rest of my life.

Our 15-page Krautrock episode outlines make a lot more sense now. Ha Love this record. So glad you finally found a copy in the wild!