For a short time during my senior year in college, I worked part-time in a record store. Actually it was a bookstore—one of those Borders-/ Barnes & Noble-type outlets with a built-in café and racks of compact discs below ground level. I honestly can’t remember the name of the store. The manager of the Music Department was looking for a “rock guy” to round out his staff, and I signed on for ten hours a week.

The other rock guy was twice my age and would rave at me about NRBQ and Ginger Baker’s drumming. He was in deep. By contrast, at that time everything I knew about rock music before 1977—which was not nothing—I had learned for the sole purpose of heaping scorn on it. NRBQ Man was a nice guy, but we didn’t have much in common, which was fine because for the most part we didn’t share shifts. I tended to be paired instead with the Assistant Manager, a “classical guy” who wore elaborately cabled sweaters and spent most of his time taking smoke breaks in the truck bay.

For this reason I was characteristically alone on the floor one weekday afternoon when two women stopped in together to shop. One was middle-aged: black hair interwoven with wild silver strands. Come to think of it, she was probably not much older than I am now. The second woman was considerably older. Grayed-out completely, with tubes in her nose leading to an oxygen tank tucked away discreetly somewhere. In her purse? On her hip? I couldn’t tell.

The older woman wanted to look through the CDs in the Classical section, and she asked me if I could get her a chair so she could sit down as she flipped through the racks. I did her one better and found her a chair on casters, so she could wheel herself down the row while she browsed. The woman settled in the chair and gave me a big smile. I felt good about myself.

Cut away now to the younger woman. She’d gone off into the Rock section. This being my area of expertise, I asked if I could help her find something. She waved me off: the racks were alphabetized by artist, after all. Cool. I settled in behind the checkout counter.

Time passed, and the elderly woman with the oxygen tubes had worked to about midway through the Classical section, pausing from time to time to wave across the floor to me and thank me again for finding that wheelie-chair for her. It was a nice chair: upholstered, with armrests, the works.

Eventually the younger friend approached the counter with a handful of CDs. I rang them up—scanned the bar codes with the beam, removed the theft controls—and read out the total. The woman gave me a credit card, and I swiped it. While the card reader was authorizing the purchase, the woman commented favorably on the store’s inventory. Her son’s birthday was coming up, and she had been fortunate to find everything on his list.

This is where I made the mistake of trying to be helpful. One of the CDs I’d rung up was the Original Broadway Cast recording of The Who’s Tommy, and it seemed like a long shot that a teenage kid would want that record. So I asked the woman: “This one’s for your son, too?”

“Yes—that’s top of his list,” she said. “He’s really into the Who.”

“Hm. Are you sure he wants the Broadway cast recording, and not the original record?”

In the meantime, the card reader had authorized the transaction, and the register had printed out a receipt, which I tore off and handed to the woman. She was looking at me, confused, so I explained: Tommy was originally a concept album written by Pete Townsend, recorded by the Who, and released in 1969. Decades later, it was turned into a Broadway musical, and what she had just bought for her son was not the Who’s record but instead a two-CD set of Townsend’s compositions, performed by Broadway singers.

The woman’s face fell. “Oh,” she said. “I think I should have bought the one by the Who.”

I nodded. “But better to catch it now. We have the Who album, too. When my manager gets back, he can back out the charge for the Broadway one, and then you can buy the other one instead.”

“Can’t I just swap one for the other and go?”

I explained to her that the two-CD Broadway recording sold for about twice the price of the single CD by the Actual Who. So if we made that trade, she’d be eating about ten bucks. “It’s fine, though,” I said. “My manager should be back in a minute.”

“But I don’t have time to wait for the manager,” the woman replied. “My friend is running out of oxygen.”

This raised the stakes considerably, and caught flat-footed by the turn this discussion had taken, I made the mistake of departing from that Cardinal Rule of Retail, which is that the customer is always right. I looked up from the pile of CDs on the counter in front of me, off to the right toward the Classical section where the older woman was by now rooting through the R- and S-composers. I made eye contact with her, she smiled at me yet again and waved, and on that information, I uttered these fateful words to her friend at the counter:

“I dunno: she looks all right to me.”

From this point onward the tone and tenor of the exchange changed dramatically for the worse, as the woman at the counter demanded to know what my medical credentials were, so that I could know from thirty feet away who did and didn’t need oxygen, when I wasn’t even competent enough to reverse a credit card transaction, and where was the manager anyway, because she had a word or two to tell him about my customer service, and this went on for some amount of time, but by no means long enough for Cabled-Sweater Man to have finished his break.

Turns out I could answer just one of the many particular criticisms and complaints this woman was streaming at me, and it was the one about reversing the transaction. I asked her for her credit card, and I ran it through the reader. I hit the button to cancel the previous transaction. The card reader asked me for a four-digit code. I turned the card reader 180 degrees and pointed the screen toward the woman.

“Your guess is as good as mine,” I told her. “There are 10,000 possible combinations. My manager knows the right one, and I do not.”

“Well, when is he coming back?”

“If you want to know the truth, he should be back by now.” These hour-long smoke breaks were a pet peeve of mine, even before they put the lives of my customers at risk. With the clock ticking, and hoping to find a way around this impasse, I proposed another possibility: the customer could make a second purchase, of just the Who CD this time. I’d throw it in the bag with the other CDs she’d just bought, and she could come back and return the Broadway cast recording at some later date.

At this point the woman accused me of trying to leverage the crisis to make another sale. There were obvious answers to this, such as it’s not like I get paid on commission, and if she was willing to put her friend’s life on the slab over a measly ten bucks, that wasn’t my choice—it was hers. But I was a quick learner and I swallowed down these arguments.

“Can you go get him?” she pressed.

“Who? The manager?”

The customer rolled her eyes. “Yes.”

“Well, I can’t leave the floor. I’m the only one here.”

The customer darkened her eyes.

“Yes. Yes: I can do that.”

I took the stairs two, three at a time, tripped once, recovered myself, and sprinted out the front door of the store and halfway around the building where Cabled Sweater was strewn luxuriously across an open truck bay, like Michelle Pfeiffer on top of a piano, savoring his (third? fourth?) Marlboro White.

“You left the floor,” he said, at first sight of me.

Hunched over, heaving, I raised a finger: give me just a minute. When I’d caught my breath, I explained the situation.

“You’re kidding,” he said.

“I’m not.”

Cabled Sweater crushed his cigarette on the lip of the truck bay and stood up. Less than a minute later, he was back behind the counter, tapping out the four-digit code that would solve all problems and abate the $10 life-and-death crisis condition. I should note that through all this, the Object of All Our Concerns was happily wheeling her way toward the end of the Classical racks—oblivious, it seemed, to the drama at the checkout counter and, as far as I can tell, accessing all the oxygen she required.

Cabled Sweater had an unctuous way about him—the better to steer him into middle management of a café bookstore—and he sent the two women away satisfied, if not happy. Despite his faults, he also had a sense of justice, and when the customers were safely out of earshot he turned to me and said, “Don’t sweat it. Just another day in retail.”

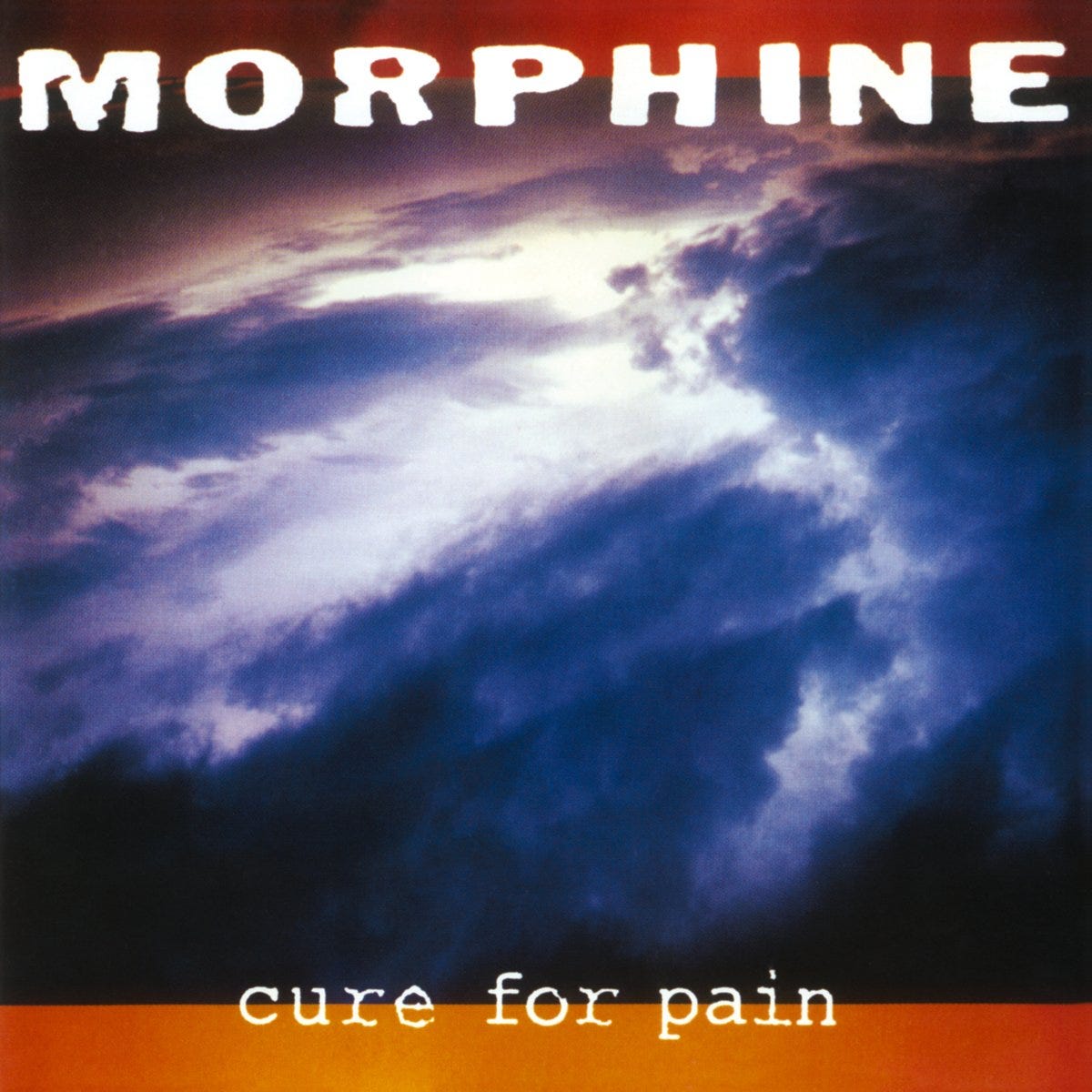

There was a shelf of CDs we kept behind the counter at the store, to play over the PA. It was a pretty random selection, and I don’t know who chose them. I remember a collection of recordings from Hildegard of Bingen, a Dead Can Dance record, and Cure for Pain by Morphine. Looking back, I suppose the idea was to limit the clerks to music that wouldn’t blast middle-aged women out of the room while they were shopping for their kids. I played that Morphine record a lot, when I had the token. “Buena” (Apple Music, Spotify) was the track that always stood out to me. So that’s what we’ll go with today. Lo-fi Boston college rock: bass, drums, sax, and vocals.

I liked this .. a LOT! One of these days we might share our experiences in our brief forays into the retail jungle.

Do you ever wish you could talk to NRBQ Man now that you are well-versed in rock pre-1977?