Nine Inch Nails, "Down In It"

This post is about First World problems—namely, driving my car in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The other day Florian and I were trying to get from an appointment north of Central Square into my old neighborhood in Cambridgeport to pick up dinner, and from there back home to Belmont. I’d been in the car for forty minutes, and I was cooked. I’d been jammed up, cut off, cursed out, rerouted, and now was locked down. At some point during this odyssey, Nine Inch Nails’ “Down In It” (Apple Music, Spotify) came on over the car radio. This lifted my spirit just the slightest bit, and I turned to The Kid and said, “This song is about driving in Cambridge.”

He nodded, and we listened in silence, stacked up in traffic in the eye of the shitstorm that is Western Avenue, between Putnam Avenue and the Charles River, in the early evening. The smell of garlic permeated the car. We were hungry, we had low blood sugar, we had foil containers of baked stuffed eggplant and chicken piccata we were obligated not to crack open until we got home, and we were ten minutes from getting off this block, much less clearing the rest of the eight miles back to Belmont.

Cue the industrial rock nihilism.

I was up above it. Now I’m down in it.

I was swimming in the haze, now I crawl on the ground. And everything I never liked about you is kind of seeping into me.

I used to be so big and strong, I used to know my right from wrong, I used to never be afraid … I used to have something inside, now just this hole that’s opened wide. I used to want it all—I used to be somebody.

All the world’s weight is on my back, and I don’t even know why. What I used to think was me is just a fading memory. I looked him right in the eye and said, “Goodbye.”

I was up above it. Now I’m down in it.

As the song played through to its conclusion, Florian laughed out loud. “Yeah: that’s exactly what it’s about,” he said. “Cambridge driving.”

Kate and I moved out of Cambridge into a neighboring town in 2007. And while I’ve continued to work in Cambridge ever since, my routes in and out on office days are masterfully plotted to keep the drama and delay to a minimum. By now I know all the traffic dodges and shortcuts, and I have emergency protocols ready to deploy in an instant, in case of road closure or detour. The only wrinkle is Tuesday mornings, because the garbage trucks are out, and if you’re not careful you might just blindly turn down a block and get stuck behind one. Aside from these managed regular commutes, I want no part of this city. There was a time when I was hardened to the very specific brand of bullshit the streets of Cambridge inflict upon their drivers, but those days are well in the rear-view now.

At this stage of life, in this cultural moment, I have zero patience for inefficiency. I accept that this is a character weakness, but I don’t think I’m an outlier here, and I don’t think it’s my fault, either. Over the past 25 years, the vast majority of the settings in which we formerly had to practice patience have been cleaned up and set straight. By way of example: no one has to sleep out on the sidewalk outside of Sears to buy concert tickets anymore. And you don’t, either, have to hit redial on your phone four hundred times starting exactly at 10 AM on Saturday until you get through to an open line at Ticketmaster, at which point it’s a coin flip whether the operator will still have seats left for you to buy. The Internet made all this Sturm und Drang go away.

Technology and management consulting have propelled society forward into an Age of (For the Most Part) Convenience. At the grocery store, you can walk right up and use the self checkout station, usually with no waiting. Or avoid the whole nightmare altogether and arrange for delivery. TSA Precheck isn’t fast enough for you? Sign up for Clear. At Cedar Point or Busch Gardens or Disneyworld, they sell jump-the-line passes. For sure, this advantage bears all the hallmarks of the eighteenth-century English class system our forefathers rejected. By rights they should make you wear a powdered wig, blush, and velvet knee breeches as a precondition to taking the fast lane into Space Mountain. But you don’t have to be born into this privilege: it’s enough just to swipe your credit card and eat the $200 charge. The point is if you can’t stand the waiting, there’s a workaround. It may cost you some scratch, but it’s there. And this is increasingly true in all walks of life.

I was up above it.

Until it isn’t. You show up at the airport, already checked in with your boarding pass loaded into your phone. You just need to print the luggage tag and drop your bag. But something in the kiosk won’t compute, and now you’re shunted into the “Special Services” line behind three dozen people, each of whom has a 20-minute, 8500-keystroke problem for the lone representative working the counter to solve.

Or you pull up at a border crossing—easy-peasy going into Canada, but on the return trip, there’s a half-mile backup. When you finally pull up at the window an hour later, the Customs and Border Protection agent asks you if you’re transporting any firearms.

“Yes, officer. I went to fucking Canada to buy guns, because it’s just too goddam hard to buy them in the United States.”

Here I am in the checkout line at Cumby. I’ve got my cinnamon bun in my hand. I could eat it and pay for the wrapper, but I need them to zap it in the microwave for ten seconds. Makes it 900% better and therefore worth the $2.29. Dude in front of me is buying $40 in scratch tickets. The clerks tear them off of big rolls hanging on the back wall, but this guy can’t decide which ones to buy. The decisional paralysis here is redolent of Sophie’s Choice or the middle three acts of Hamlet, except that there is actually nothing at stake here, and every sensible person in this line knows it.

“Dude, how about you just give me your forty bucks, and I give you back these two singles? That way we skip the middle part, and the rest of us can get on with our day.”

Oh, and has anybody been to the Registry of Motor Vehicles lately?

Now I’m down in it.

And that’s the thing. If you’re down in it all the time, you’re inured to these conditions and can accept them in good spirits. If you live in Europe, you expect that on any given Tuesday some category of person you didn’t realize was indispensable to the execution of your plans has gone on strike, and now you’re screwed. Contrast a middle class American in his fifties who is resourceful, has all the right apps, and a reasonable amount of money. A guy like that can navigate through 95% of his life with relative ease and no waiting, up to the point where that last unwieldy 5% feels like the Ninth Circle of Hell, or as I mentioned in passing two weeks ago (see “I’m in Love with the Girl, etc.”), the Hertz car rental line at Cleveland Hopkins Airport.

“I signed up for #1 Club Gold precisely to avoid having to stand in this line for ninety minutes. A half-century ago we put a man on the moon, and I’m holding in my hand a device with 100,000 times as much processing power as the computers that piloted that spacecraft. I can publish a 10,000-word rant about inefficiency and Nine Inch Nails for anyone in the world to see instantaneously. Why does it still take fifteen minutes to consummate a goddam rental car transaction?”

Note: I don’t say these things out loud. I’m not a Karen, after all. I’m plugged in to what’s going on in Ukraine, and I’m aware of the humanitarian crises in sub-Saharan Africa. I know better than to say something that’s gonna land me on YouTube looking like some kind of jerk. I’m just writing here what passes through my mind in a given moment when the circus music comes on, the clowns come out, and I’m stuck in that 5% Purgatory seething about the correctable human failures and omissions that are jamming up my day.

Good God, this post is going to get me canceled … but from what? Ace in the hole there, Reader: you don’t really exist!

Okay okay okay. So I acknowledge that I am carrying a lot of baggage and not so much tolerance with me, when I cross into Cambridge in my car on a given Wednesday night. But it’s not just a case of me—or for that matter a case of a thousand people with the same or similar deficiencies of character crammed into the same system together, trying to get over, around, and through one another from Various Points A to Various Points B. On the Road to Meltdown, Cambridge is meeting me—all of us, really—more than halfway.

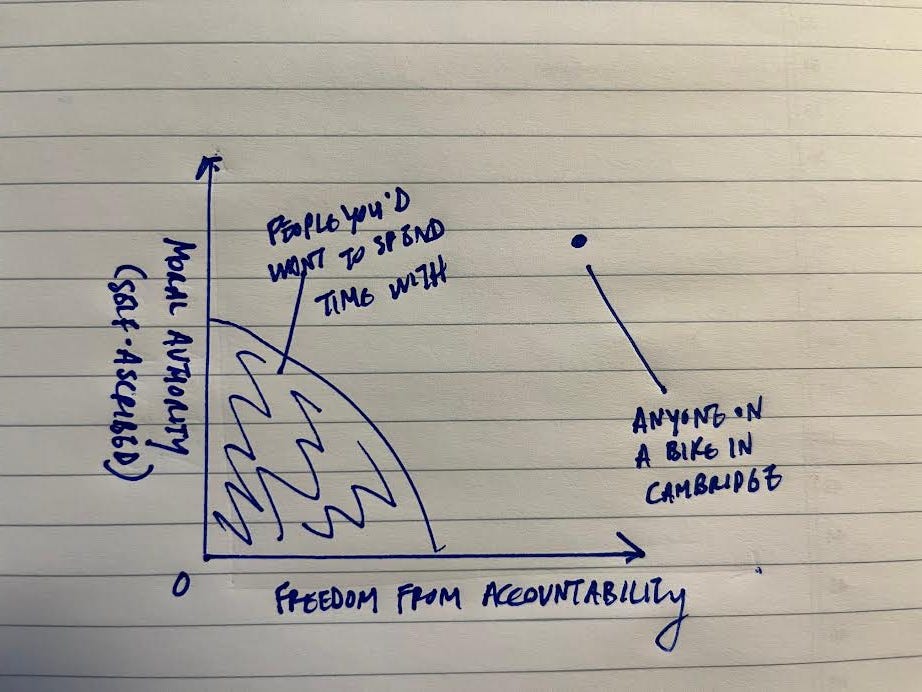

Let’s take a minute and talk about the bicycles. There is not now, nor has there ever been, a more insufferable class of person than The Cambridge Cyclist. Consider a graph, where the x axis measures self-ascribed moral authority and the y axis measures freedom from accountability. The most insufferable person—that is, the person furthest from the (0,0) origin plot on that graph—is That Guy on a Bike in Front of You in Cambridge.

That Guy’s foundational belief, his Nicene Creed, is that the traffic laws exist solely to protect him, and accordingly, he has no obligation himself to comply with any of them. Watch him in action: ever ready to throw The Bird at a car that turns across his lane on a green arrow, and then he plunges right into a crosswalk against the light, scattering pedestrians in his wake.

There’s a particular woman I see from time to time. She’s probably 112 years old. She rides a Schwinn from West Cambridge in through Harvard into Central Square and beyond. It’s actually kind of inspiring to see her on the road at her age, until you realize that what’s powering her legs into the pedals, day by day, is groundless, bottomless outrage and judgment of others. She has a whistle crammed in between her teeth and dangling out of the side of her mouth, like FDR’s cigarette holder. Do anything she doesn’t like, and you’ll get a blast of her whistle.

Once on the way to MIT I had to cross the center line to pass her five times. Why? Because each time I passed her, a light would turn red, and I would have to stop. Then she would ride right through the intersection, blasting her whistle at all the cars that had the right of way. Then the light would turn green, and I’d have to pass her all over again. Not exactly hugging the sidewalk, this one, so you had to take on oncoming cars to get around her. If you didn’t give her a wide enough berth: whistle blast.

This brings me to another reason I get fried on the road in Cambridge: I don’t respond well at all when I’m accused of doing something wrong. Like, I seriously overreact, and I carry that heat with me for hours afterward. Again, I acknowledge the character weakness, though I’ll submit that this one arises from my good character, in that I really do strive to do good and act justly most of the time. The problem is the streets of Cambridge are inimical to, and destructive of, virtue. I can feel it draining out of me as I trundle down the road and streams of curses back up behind my lips. Nevertheless I hold back and try to power through, to be The Change I Want To See on Bishop Allen Street, and for my efforts I am whistled for trumped-up flagrant fouls by Marge Schott on a bicycle.

Republicans and libertarians like to argue that motorcycle helmet laws actually result in more accidents and injuries, because knowing their heads are protected makes bikers more reckless. I think Cambridge should take this logic and run with it. I think the City should pass an ordinance that gives every licensed driver two free shots at a cyclist. To be clear, this is a lifetime limit, and you have to be traveling under 15 mph at the point of impact. Nobody needs to be seriously hurt here. I just think having to look out across a landscape dotted with cars, any one of which may have a driver at the wheel with one or two unused chits she could spend to send you sprawling, would do wonders to nudge The Cambridge Cyclist down and to the left on that Insufferability Graph.

But what do we get instead? We get cement barriers and PVC palisades on the most traveled thoroughfares—Brattle Street, Main Street, Mass. Ave.—gouging luxurious bike lanes out of Roads That Used to Be Hospitable to Cars. And going forward (if you can call it that) we drivers are condemned to unendurable stretches of sclerotic misery, backed up for miles in one-lane traffic behind red lights, stop signs, crosswalks, construction sites, and double-parked cars with blinkers on to say, as if it were less offensive, I realize I’m making you wait—it’s just my time is SUPER-important. What’s worse: with every new bike lane, the City adds to the overweening self-importance of its Cyclist base. Down the ride they smugly ride, leaving the rest of us, sectioned off now from the real enemy, with no option left but to turn on each other. Which we readily do.

I want to be fair to the Cambridge police. Last year they pulled me over for thumbing out an email at a red light on Mt. Auburn Street. They were exactly right to do it, and they were generous to let me off with a warning. Points duly awarded. And I remember a time years ago when I was walking to Harvard Square, headphones on, and I heard a strange crumpling sound to my right. I looked over to see a station wagon rolled over on its side. To this day I can’t reconstruct how this could have happened: i.e., I can’t figure how you could be going fast enough on that stretch of road, or what you could possibly do at the wheel, to cause your car to go up on two wheels, much less come to rest at a 90-degree angle to the ground. Chalk it up to Cambridge being Cambridge. Anyway, for a good five minutes after this happened, everyone in the area, including me, was fully freaked out. It was complete chaos, and the first sensible person to arrive on the scene was wearing a blue uniform and badge. The officer brought order and calm to the situation almost instantaneously, and I remember walking off thinking, That’s why we have police.

So let’s talk now about what we don’t need from police. We don’t need police to tailgate us through an intersection at night, then flip on the lights and bust us for proceeding under a yellow. Seriously: had I braked for the light as required, the cop would have rear-ended me. I wonder what that citation would have looked like. Likewise, we don’t need officers standing by every pothole repair project, schmoozing with the workers while the traffic stacks up. Now and again you’ll see bumper stickers around town that read POLICE DETAILS SAVE LIVES. This tendentious slogan issued from Fraternal Orders statewide fifteen years ago, when the Governor finally said the quiet part out loud: The double-time pay we give these guys, only some subset of whom actually do the job—isn’t it really just a boondoggle?

Cab drivers: you don’t see as many of these, because of Uber and Lyft—unless they’re staging a traffic slowdown to protest Uber and Lyft. That was a fun day. Here’s an interesting fact: it’s illegal for a cab driver with a Boston medallion to pick you up in Cambridge. If he’s caught doing it, he has to pay a $500 fine. The taxi industry loves to get together with the City to write laws. Yet the laws they don’t write—like, for example, the law against U-turning in the middle of a block across three lanes of traffic—are optional. You hear these legends about how a single moving violation can cause a cabbie to forfeit his license. That simply cannot be true, or if it is, then the police have adopted an unwritten policy not to enforce the laws against taxis, so as not to deprive anyone of their livelihood.

Pedestrians aren’t so bad, really. Most of them are college or graduate students, and therefore capable of learning. Accordingly, it can be rough at the start of the academic year in September. Lots of bodies hurling themselves into the road at unexpected moments and pinging off your side mirrors. But as fall turns into winter, and winter into spring, the students acquire a better sense of the traffic patterns and their own mortality. Then the summer comes, and they’re gone for three months. And on or around Labor Day, the cycle begins anew.

Probably the hardest thing about moving out of Cambridge was giving up our City-wide resident parking permits. For fifteen-plus years now, we’ve had to jockey with all the other out-of-towners for metered spaces. And you park at a meter in Cambridge at your own peril. The parking enforcement officers are ninjas. Really, there’s no other explanation. The moment your time expires, they’re there. They write you up, leave the ticket, and instantly disappear—parkouring up the side of a building, slipping through a sewer grate, dissolving into the general population. You get back to your car two, three minutes after your time’s up, and you never saw them coming or going. But there’s the $30 ticket, marking their passage through your life. You’re lucky they didn’t cut your throat with a katana. Ay, verily: if the rest of Cambridge’s city government performed its functions 40% as effectively as its parking enforcement guild, we’d be living in a golden age.

It’s most certainty true that when he wrote “Down in It,” Trent Reznor wasn’t thinking about road rage, or—what is a more apt description of my state of mind under these conditions—road demoralization. First off, I know for a fact that Trent was living in the Midwest when he wrote this song. He might have vacationed in Boston, and even played a show up here, but he surely wasn’t clued into the Hobbesian dog-eat-dog Lord of the Flies experience of driving through Fresh Pond Circle or navigating the scaled-up sliding numbers puzzle that is the Porter Square parking lot. Second, and more to the point, this song’s lyrics, while generally stated—i.e., we don’t know exactly what’s been done to Trent to generate these feelings of desperation and regret—are surely describing a dragging-down that is more consequential and enduring than that Memorial Drive construction project could ever accomplish.

That said, a grown man living in the suburbs with a loving family, reliable work, and relatively few indignities to suffer over the course of his days necessarily has to reach a little, to identify with the dark and desperate content of a Nine Inch Nails track. Two Wednesdays ago I did just that, and the laugh Florian and I had over it took at least some of the edge off that rocky drive home. Soon enough we did cross over the border into Belmont, and we were up above it again.