Back in 2018 the New York Times published an op-ed by the economist Seth Stephens-Davidowitz about the formation of musical taste. Stephens-Davidowitz (um, let’s call him “Professor Seth”) accessed Spotify analytics—specifically, hit counts and release dates for songs, cross referenced to age demographics of listeners—and drew the conclusion that “[t]he most important period for men in forming their adult tastes were the ages 13 to 16,” and “[t]he most important period for women were the ages 11 to 14.”

Reading this article just now prompted me to go downstairs to consult my copy of The Compact Oxford English Dictionary, so that I might then write something sharp-elbowed in response to this, e.g.:

Congratulations, Professor for discovering this phenomenon. But the word “nostalgia” dates at least as far back as 1770.

Splashed across some 20 volumes in its non-compact edition, the OED not only defines nearly 300,000 words; it traces their origin, quoting from the earliest identifiable published text where its researchers could find the word and then tracking changes in the word’s meaning and usage through the ensuing years. The compact version is cool as shit—it’s a tome in its own right. My edition has 2371 pages (the last word is “Zyxt”), and each page has a 3-x-3 grid of scaled-down pages from the regular edition in microtype. The dictionary comes with a magnifying glass. Just now when I opened the book—for the first time since my eyes made their late-forties “adjustment,” so that I can’t read printed text unless I hold it at arm’s length + six inches—I was legit worried I’d need to go find a second magnifying glass to put over top of the OED magnifying glass. Fortunately that wasn’t the case.

I don’t need a magnifying glass to read the inscription my grandmother, an English teacher, hand-wrote to her English Lit-major grandson in the front of the book:

I am proud to be the one to give you this dictionary you want for this Christmas 1997. You will have many more dictionaries in your lifetime—let’s hope this is one you always like best.

Love you,

Gram

After reading that note, I felt about thirty degrees warmer inside, and I scrolled up in this post and reformatted that earlier snide comment to strikethrough text.

Dictionaries, records, a gift inscription from a dearly loved grandmother lost too long ago: nostalgia is bearing down on me in the worst way as I write this. To be fair to Professor Seth, he wasn’t claiming to have discovered it. He was looking into where nostalgia comes from, and specifically, how the most important and enduring imprints are made upon the most impressionable minds, at a most critical time in their development. Then time passes as it does—relentlessly, we can all agree—and in rare moments of relative tranquility in our busy lives we find ourselves reaching back to try to revisit the moments that left these imprints. We find that we can’t do it, and it hurts.

That’s nostalgia. I expect that in most of what I write here, I will be up to my neck in it, if not fully submerged and gasping for air. In the hope of keeping these posts from becoming uniformly maudlin and formulaic, I will try, very hard, not to wallow in nostalgia all of the time here.

The rescue strategy I’ve adopted for this post—which God bless you, Reader, I am turning to only now, 500 words deep in the writing of it—is to ditch nostalgia completely and introduce an altogether new and different concept I’m going to call neverstalgia (n.): the pain of having never experienced something great in the first place.

“Neverstalgia” is not in the Oxford English Dictionary. Turns out it does appear on UrbanDictionary.com. While I swear to you I coined the term independently a week ago, when I first outlined this post, I figured most likely someone on the Internet must have had a similar idea. So I Googled the word, and sure enough, the top search result linked to that Urban Dictionary page. Their definition—“nostalgia for what has never existed”—differs from mine in a critical respect:

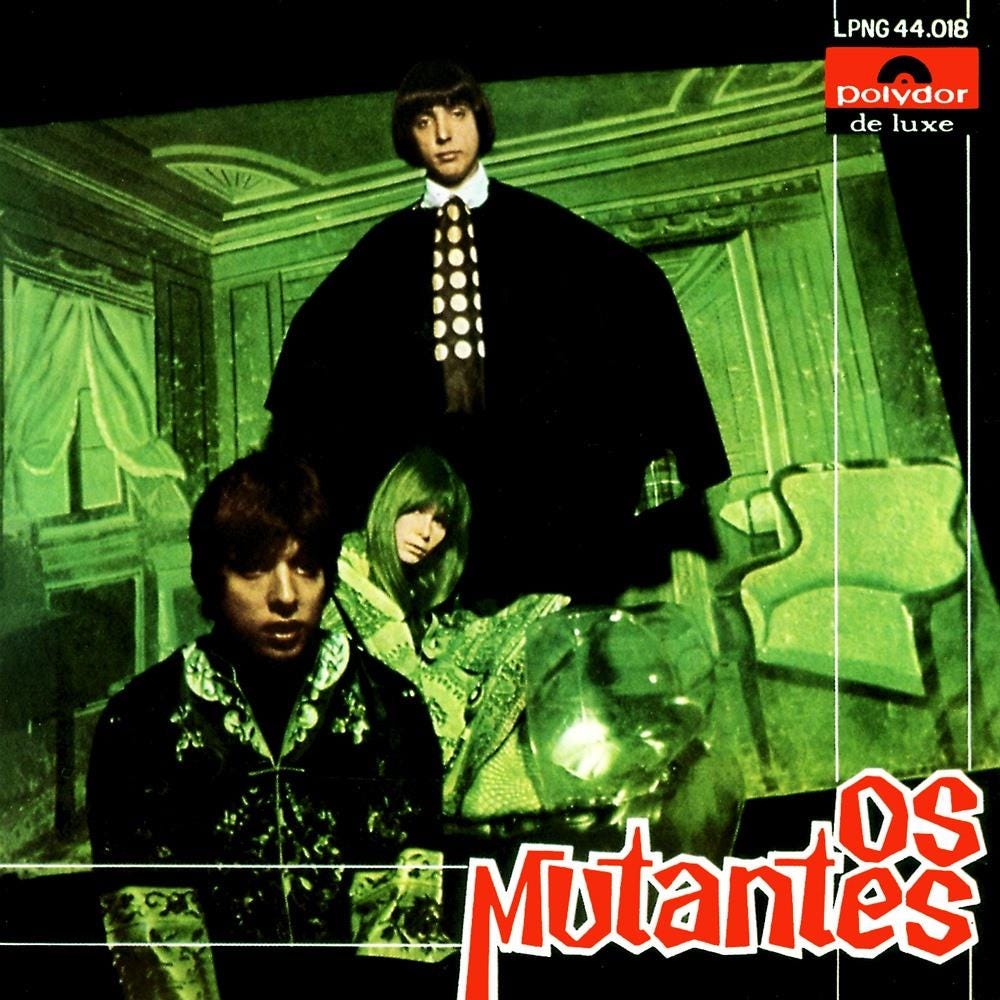

Os Mutantes most definitely existed.

And my sense of loss with respect to Os Mutantes is twofold: first, born too late and in the wrong place, I wasn’t there when these three teenagers sprung their wild and brilliant music on a repressed Brazilian polity in 1968, and second, until two years ago, I hadn’t even heard any of their recordings, much less watched the stunning archival live footage here, or here, or here:

Now I’m trying to make up for lost time, but there’s a gap between <what I’m after> and <what’s possible> that can’t be closed. In space and time, I’m an ocean away from Os Mutantes, and that ocean is filled with neverstalgia. The sea levels rise with every minute I spend playing their records.

I held out against late sixties music, and psychedelia specifically, for a long time, because their exponents annoyed the hell out of me. There was a time in my teens when I would have told you there’s nothing more culturally alienating than being a bystander while a Boomer pours out his nostalgia for 1967. Thirty Super Bowl halftime shows later, I know that’s not true. And when I look back on why I felt that way, I’d have to say half of my sense of disconnect had to do with the speaker’s sense that nothing in the world was more important than their youth culture, and the other half I’d ascribe to the “you of course couldn’t possibly understand any of this, because you weren’t there” bullshit that always followed. My response to this was Fine: that much easier to walk away.

Now that I’m inflicting much the same generational supremacy bullshit on my own kids, I see now that I don’t have to be so stiff and ideological about music. I can carry the banner for punk and new wave, shoegaze and Britpop, and I don’t need to wall out psychedelia, Tropicália, or Krautrock, to do it. After all, the bands that I formed attachments to in my tender years—thank you, Professor Seth—found their sounds and wrote their songs with their own earlier attachments in mind. The Stone Roses and Love. Pulp and the Smiths. Stereolab and Neu! These bands wear these influences on their sleeves, and they’re practically crying out for their fans to dig into them.

So over the years I’ve worked my way back to the late 1960s, not because Boomers told me to, but because, I dunno, Noel Gallagher did? Oasis track back to the Beatles. Sgt. Pepper leads to Os Mutantes S/T. It takes exactly two leaps to make this trip. But in the course of exploring the vast treasury of music that is rock ‘n’ roll, there are so many possible leaps to take in any direction, so many paths to chart, that decades can pass before you ever make that simple two-step journey from Manchester to São Paulo.

Having taken the scenic route to get here, let’s square up now and talk about Arnaldo Baptista, Sergio Dias, and Rita Lee. Let’s talk about the Tropicália movement and how these three self-identified Mutants threw dirt in the face of an essentially fascist government with just enough subtlety to keep out of jail, and smiling ear to ear the whole damn time. And let’s talk specifically about “Panis et Circenses” (Apple Music, Spotify).

We’ve seen these triumphant arrivals before, when on Side A, Track 1 of its first LP a band announces itself as a perfectly conceived and fully realized artistic force. “Blister in the Sun” (Apple Music, Spotify) from The Violent Femmes comes to mind. “Obscurity Knocks” (Apple Music, Spotify), by the Trashcan Sinatras. Statements so compelling and emphatic that you tell yourself if they never recorded another song, it would be good enough … but thank God that’s not the case.

Os Mutantes didn’t write “Panis et Circenses.” This was a composition of Tropicália’s elder statesmen, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. The song first appeared on the Tropicália ou Panis et Circenses compilation record, which by its title offered a choice to Brazilian listeners: you can content yourself with the bread and circuses government gatekeepers approve for you, or you can listen to **us**.

This is the part of the post where I’m supposed to describe what I hear in this song. All I can say is thank God we live in the Streaming Age, so you can click the link up there and listen to it yourself. It’s every bit of the Sgt. Pepper LP—the steampunk, the songs of the angels, the thumbed-out ASMR bass guitar, trumpets on top of trumpets on top of trumpets—but Latin-inflected and crammed into a clipped 3:40. There is no end to what you can hear in this song, and therefore no end to the number of times you can play it. Mutants these three surely were: technically gifted musicians, but sound-forward and fun-first. This isn’t alienating prog-jazz wank. It’s art, shimmering and perfect, and when they ramp up the tempo, it shakes your booty. I hear this song, then I hear “A Minha Menina” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Caminhante Noturno” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Haleluia” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Oh! Mulher Infiel” (Apple Music, Spotify), their cover of “Baby” (Apple Music, Spotify) …

Goddamn, I was born twenty years too late.

Disclaimers here are important: please don’t read this like I’m pining away for a time when I might have been part of The Struggle, or chasing a cheap holiday in other people’s misery. Shit was real in Brazil, and Os Mutantes certainly didn’t bring down the military dictatorship there, which would last until 1985. I only wish I could have seen this extraordinary band perform this joyful music when and where it mattered enough that it scared the regime. And I wish I could understand what the most-impressionable tween/ teen listeners in Brazil felt, when they first heard it.

Short of that, and for sure it will always be short of that—I’m gonna keep dropping the needle on my three Mutantes records and the Tropicália compilation, and I will rock out through every note, every screech of feedback, every drum stroke. (Sometimes I could do without the slide whistle.) It’s a consolation, as I get older, to know that I can form attachments to bands and music that feel every bit as strong and intense as what I felt as a teenager.

More than that, it’s just a joy to listen to Os Mutantes.

You have a very good about being able to hear anything in this. It’s hard to tell if it’s directly from these guys or mutated and passed on by the Beatles but I clearly heard an influence through NIN in there as well. Right after the record stop. The lumbering section that immediately follows feels like it could have influenced Reznor on The Fragile. The title track has a section about midway through that feels like it’s cut from the same cloth.