Since 1972, on or about the summer solstice, Michael Eavis has hosted a (mostly) yearly music festival on his farm in Pilton, Somerset, England. It’s the Glastonbury Festival of Contemporary Performing Arts, and if you haven’t heard of it, you must not be British (and may not be American), because Glastonbury is fucking huge.

In 1998, when I was solo-touring the U.K. and Ireland, I sort-of-went to Glastonbury. It wasn’t the greatest weekend of my life. An objective observer reviewing the data would probably conclude that it it sucked. But it was definitely among the most memorable experiences of my near-50 years on this Earth, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Let’s start with the lineup, which was insane: more than 1000 performances splayed across seventeen stages over three days, Friday through Sunday. Bands I was jumping out of my shoes to see at the time included James, Blur, Sonic Youth, Pulp, St. Etienne, Catherine Wheel, Spiritualized, the Jesus & Mary Chain, Cornershop, Portishead, Primal Scream, and Fatboy Slim—and that was just the first tier. Stereophonics, Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros, Rocket from the Crypt, Placebo, Ian Brown, Kristin Hersh, Doves, the Chemical Brothers, Julian Cope, and, for crying out loud, Bob Dylan were also on the bill.

I had admired this lineup for weeks, but from a distance, because I had understood that the event was sold out. There’s a longstanding tradition of “punters” (as fans are called over there) jumping the fence into Glastonbury, for the most part with impunity, at least in those days. Per the BBC: “[i]n 1995 it’s estimated that 80,000 bought tickets—and as many again gatecrashed.” Thing is, I’ve never been much of a rule-breaker. But I can be resourceful, and somehow, some way I came to learn that a last-minute tranche of tickets had become available at the Glastonbury Information Centre.

When I found this out, I was on the west coast of Ireland, T-minus 24 hours from the festival’s start time. To get to Glastonbury, in the West Country of England, I had to take a train across Ireland to Dublin, a bus from the train station to the port terminal, then the Stena ferry (see “Columbia”) to Holyhead in Wales, then a train to Bristol, and figure things out from there. Dublin to Bristol was an overnight project, and I remember sleeping for maybe an hour on a bench in the Bristol bus station. A man who did not turn out to be a serial predator offered me a ride to Glastonbury, so yeah: you can add hitchhiking to the list of travel modalities.

Riding down the A39 in this gentleman’s car, I sized him up. I was bigger and younger than he was, so if this ride took the sort of turn my mother had always warned me about, I figured I had at least a 60-40 shot at winning the fight—provided I didn’t fall asleep in the car. This was the sort of chance I was prepared to take to get to Glasto ’98.

Dropped safe and awake, as it turned out, in Glastonbury’s town center mid-morning, I entered the adorable brick tourism authority building to pick up my ticket. Having paid by credit card over the phone before jumping the eastbound train to Dublin, I was pleased to see that the “Information Centre” was a bona fide community organization that did, in fact, have tickets to sell. An elderly woman in a sweater reached into a drawer and pulled out an envelope with my name on it and my ticket inside. So far, so good.

It was misting, and the weather forecast called for more rain. Down the block from the Information Centre I found a general store-type outfitter selling what a handwritten placard described as a “waterproof sleeping bag.” These were moving quickly, and I felt lucky to get one. I strapped the sleeping bag to the top of my German army surplus backpack, and I jumped the next available shuttle bus to the Eavis Farm.

You’ll note that I have not said that I was carrying a tent. This is because although I was twenty-four years old and largely self-reliant and habituated to adult living, I had no real plan for where and I how I would sleep over the next three days. And I had no clue what was coming.

Zero.

Here is a map of the Glastonbury site at Eavis Farm in 1998. See if you can find a hotel on it. Or a hostel. Or any kind of shelter wherein a Yank who has been awake since Thursday morning could set down his “waterproof sleeping bag” at the end of the night.

If you do see such a place on this map, please don’t tell me about it now, because it’s too goddam late for me to know.

Upon arrival at the festival grounds, my first objective was to dump my massive traveler’s backpack and the second, smaller backpack I was wearing over my chest, so I’d be freed up to take in some of the shows. Somebody told me there were lockers. Now the map posted here shows that there were lockers in several locations around the grounds. As far as I knew at the time—and really up through and until I Googled for and found that map a few minutes ago—there was just the one location in the furthest northwest corner of the site, a good five- to ten-minute hike from anywhere else you’d want to be at the festival. When I got there I paid some modest amount of money to drop my gear, and then I walked off into the grounds to see who was playing.

Almost immediately it started to rain. Hard. And as the ground under my feet turned quickly into mud three, four, five inches deep, I started thinking about whether I could fairly expect to climb inside my “waterproof sleeping bag,” with no other cover, and get to sleep later that night. At this point I was taking in Rocket from the Crypt, who were pretty damn fun to watch, but in the moment I was bit distracted by these other, practical considerations. So I took a few dozen steps back from the stage and started questioning other punters passing by:

Uh, is there somewhere you can sleep if you don’t have a tent?

Somebody told me about a “Christian Charity Tent.” I don’t remember if this was exactly what it was called, but the gist of it was that some charitable Christian folks had set up a tent to take in People Like Me Without a Plan, and so long as I wasn’t averse to fielding one or two evangelical appeals at the point of entry, I could set up shop and sleep there, out from under the rain.

Off I went to claim space in the Christian Charity Tent. To do that, I had to hike back to the Furthest Northwest Corner of the Site to get my “waterproof sleeping bag” to bring down and lay out on the ground before others snatched up all the vacant space. Which I did, and then I went back out to see some more bands. I was a little concerned that, having walked away from my “waterproof sleeping bag,” someone might go into the Christian Charity Tent to steal it or—which would be just as consequential—the patch of ground I had reserved underneath it. But I convinced myself I could rely on the charitable Christians to keep a watchful eye over my turf.

Back, then, to take in some more shows. I saw Foo Fighters—holy crap! I didn’t even mention Foo Fighters were on the bill!—and after them James, who were for me the crown jewel of this lineup. James would cut their set short, so that the punters could watch the second half of England’s World Cup match played live on the big screen behind their stage. This was a tragic result, but given the composition of the crowd I was in no position to argue. Colombia 0-2 England, in case you were wondering. Cheers and chants rang out across the grounds: Football’s coming home, and so on.

The rain kept falling. I distinctly remember water draining off the brim of my plaid fishing hat, which from time to time I would take off and wring out.

Not long after Foo Fighters and James, I went back to the Christian Charity Tent to dry off, and I noticed there and then for the first time that the tent didn’t have a floor. To be sure, it had no less of a floor than when I’d dropped in earlier with my “waterproof sleeping bag.” It was just that this feature (or lack of one) was more pronounced now, because the lush patch of soft grass I remembered from earlier was long gone. Torn up by the boots of the fifty or more people who were shacking up here, and what was left was mud. Not so squishy as the mud outside, and without the standing water, but mud all the same.

The charitable Christians handed me a pink blanket. I took off my shoes and socks and dug my pruned-up feet into the mud, which was sweet relief. I draped and tucked the blanket around my waist and dropped my pants. I had to get out of these wet clothes straightaway.

“You’re gonna want to put your shoes on, mate,” a punter said to me. He gestured in the direction of four or five other punters who were sitting in a circle nearby. These punters were shooting heroin. “Don’t want to step on a spike, do you?”

I was off like a shot out of that tent. Shoes back on, wallet and other essentials pulled from my pants pockets, naked from the waist down under the pink Christian charity blanket—I made a beeline to the Furthest Northwest Corner to pull dry clothes out of the locker. Along the way I thought a little about Christianity, in its various forms. American Jesus most certainly would not have opened up his tent to skeevy smackheads who had no home. Bible Jesus might have been a bit more hospitable, but even he wouldn’t have let them shoot up on the premises. Would he? On the way back from the locker I decided that English Jesus was way too accommodating, that the Christian Charity Tent sucked, and that I should spend as little time there as possible. Rolling over on used hypodermic needles in the middle of the night was a rough prospect.

Friday night’s schedule called for Portishead to headline on the Other Stage. (The “Pyramid Stage” was the main stage, reserved for the biggest acts, and the “Other Stage” was for second-fiddles.) They were due to come on momentarily. I would go see Portishead, who I was dying to see, and when that was done, I would reevaluate the sleeping situation.

Now where the hell was the Other Stage? I wandered around aimlessly in the dark. People were carrying flashlights. I wasn’t. It hadn’t occurred to me that I would need one to get around the site at night. Other people were carrying torches—literal torches with fire, and not just flashlights by another [British] name. I followed the literal torch carriers, because it seemed to me likely they’d be in search of Portishead. They were not, as it turns out, and I found myself instead at the Pyramid Stage, with Primal Scream just coming on. I considered whether to keep looking for Portishead, but by this time [checks watch] they would have been well into their set. Better to stick with the band in front of me.

Here’s some of what I missed:

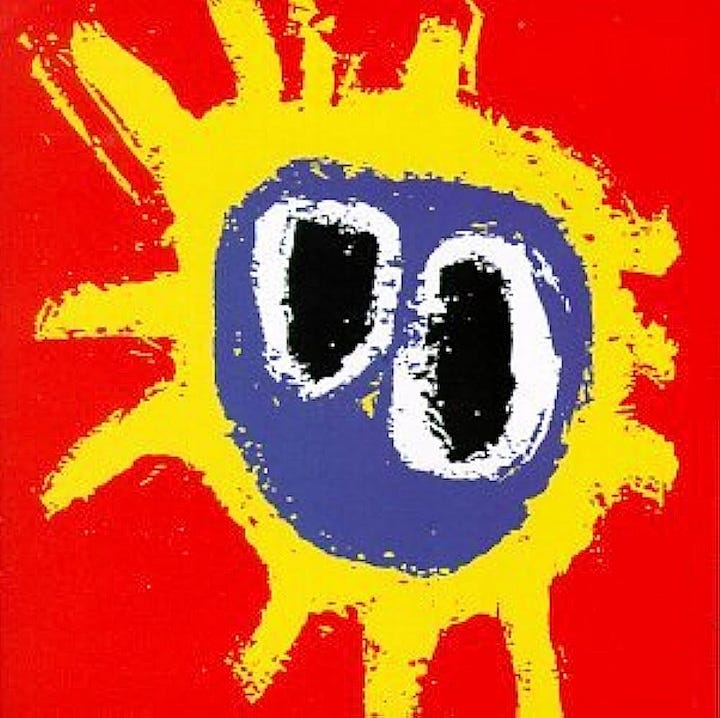

Primal Scream was touring on their Vanishing Point LP, which I did not own and therefore (in those days, before the streaming services) hadn’t heard. They played seven songs off that record, and only two from their 1991 magnum opus Screamadelica, which was by then well in their rear-view mirror, if not mine.

Let’s step away from Glasto for just a minute to talk about Screamadelica, a wild-eyed mix of Stones jams, Madchester psych rock, and acid house dance music. Its lead-in single, “Loaded” (Apple Music, Spotify), was a rework of an earlier, blues-rock track called “I’m Losing More Than I’ll Ever Have” (Apple Music, Spotify), from their first LP. “Loaded” is Primal Scream at the top of its arc. For sure they made other terrific music on and after Screamadelica, but nothing quite compares to this song, with its baggy groove, slinking bass line, looped bongo track, and unforgettable manifesto:

We want to be free, to do what we wanna do. And we want to get loaded, and have a good time.

In a stunning upset—and I’m sure I was upset—Primal Scream did not pay “Loaded” that night. Nevertheless, it’s one of two songs I’m assigning to this post, because first of all it’s the best Primal Scream song, and also because it perfectly captures what this festival experience could have been.

After about an hour, Primal Scream finished up, and I went back to the Christian Charity Tent to consider my next steps. By this time the rain had pretty much stopped, but due to (1) the peculiar drainage conditions on the festival site, and (2) the particularly low-rent district occupied by the Christians, water was pouring in from an adjacent downslope under the side of the tent. My “waterproof sleeping bag” was entirely swamped, with the result that unless I quickly made close friends with a punter with space in a private tent—and there was no prospect of that—there was literally nowhere on the festival grounds where I could lie down without soaking through to the bone. That took sleep off the table, which was unfortunate because by this time I had been up for 36 hours, minus the forty winks I’d grabbed on that bench in the Bristol bus station.

The punter who had warned me about the needles resurfaced, and we got to talking. He was probably in his late 30s. Said he was from Wiltshire, which meant next to nothing to me. He would follow me around for the rest of the night, or at least until he played his hand and told me an unmemorable story about his lousy situation in Wiltshire and asked me for money. I gave him, I dunno, thirty pounds and he moved on. I rationalized this transaction to myself in the way that tourists targeted by locals tend to do: he had either provided thirty pounds’ worth of company while he was around, or I had bought thirty pounds of tranquility by getting him to leave. Or some combination of the two.

Just before dawn I was standing down by the Druid stone circle. There were a handful of aging hippies here. They may have been at the first Glasto in 1970. They may have been hanging at the stone circle ever since. One of them offered to sell me LSD.

“Will it bring the sun?” I asked him.

“Maybe,” he said.

No guarantee, no sale. I leaned against the monument—there was no sitting on the ground—and closed my eyes. Daybreak did bring the sun, as it turned out. I found I was starving. I walked over to the market area. The only open food stall was serving ostrich pie. This was a complete non sequitur: maybe I had bought the acid? I bought one and wolfed it down. It was purple on the inside, piping hot, and it scorched the roof of my mouth. Bits of flesh tore loose and were hanging down in my mouth. It hurt like a bitch. Bad trip.

An Army-Navy surplus outlet across the way was advertising a waterproof camo full-body haz-mat suit, complete with combat boots and gas mask. This getup was priced as a package at 150 GBP, and it looked like it would fit me. I thought long and hard about this. If I buy that, I figured, I could put it on and lie down right here and sleep for six hours. In this fucking swamp. And when I got up, I’d be the biggest, driest bad-ass in this place. In the end I decided I’d be throwing good money after bad, and I chucked it. Looking back, this should have been a closer call, but 150 pounds was a big bite for my travel budget, I was pushing 48 hours without sleep, I had a pounding headache, and I felt a sore throat coming on.

I crossed the grounds carefully, squishing and slipping as I walked. I revisited the Furthest Northwest locker one last time, pulled my baggage, took a hot shower in the “Deluxe Privies” north of the Pyramid Stage, and put on another set of dry, clean clothes. Then I got the hell out of Glastonbury.

I wasn’t halfway to London on the train when the fever hit me. On arrival I found the nearest Internet café, sat down in front of a computer, and wrote out a 10,000-word hallucinatory email to everyone I knew, describing in detail the events of the previous two days. I like to think that message is not completely lost by now—that it’s tucked away on an archival server somewhere in California or Ireland, or some digital packrat friend of mine has his email saved from June 1998. I’d love to compare that message to this post, to see just how much of this I have wrong a quarter-century later.

I left that Internet café, went directly to my hostel in Camden Town, and slept for the next 24 hours straight. 115 miles away, Catherine Wheel and St. Etienne and Blur and the Jesus & Mary Chain and Cornershop and Fatboy Slim and countless other artists of note and quality played their sets while I slept. I woke up in time to catch the late Sunday acts on the telecast, if I had wanted to. But by that time I was done with Glastonbury.

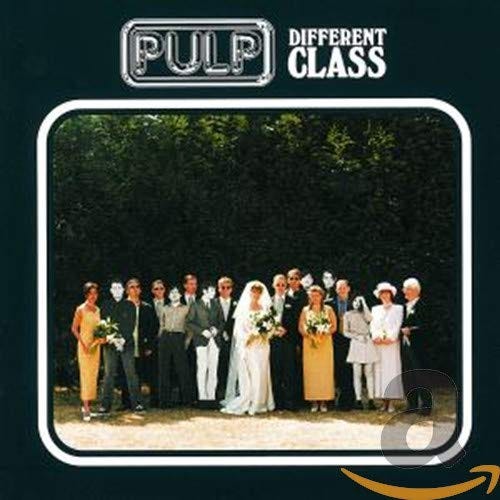

Pulp headlined on the Pyramid Stage Sunday night. They of course played their melancholy festival anthem, “Sorted for E’s and Wizz” (Apple Music, Spotify), in which English national treasure Jarvis Cocker asks several hard questions about rock festivals, beginning with these two:

Is this the way they say the future’s meant to feel? Or just twenty thousand people standing in a field?

Multiply that figure by ten for this particular case, but yeah: go on, Jarvis:

I lost my friends, I dance alone. It’s six o’clock. I want to go home. But it’s “no way,” “not today”—makes you wonder what it meant. And this hollow feeling grows and grows and grows and grows, and you want to call your mother and say, “Mother: I can never come home again, ’cause I seem to have left an important part of my brain somewhere in a field in Hampshire.”

Or in my case, in a field in Somerset.

I truly enjoyed reading this wonderful adventure you got to partake. I need to get to see more music!