There’s a saturation point in every conversation with every new person you meet at every dinner party, where the small talk is just about tapped out and the even smaller question is asked: What do you do? For my part, I’m damned if I’m the one asking it. People do lots of things, and the most interesting stuff comes outside of work hours. So more often than not, I’m on the receiving end of this line of inquiry. And I have a schtick for it:

“I’m a lawyer,” I say. [pause] “Despite my best efforts.” And from time to time I might have alongside me a champion who steps up and says: “Actually he’s a writer. Just not published yet.”

Yet. Twenty-eight years and counting. Cards on the table: I’m not really a writer. A fairer characterization is I’m parked in that gray zone between writer and person who sometimes writes. It’s a lack of discipline that condemns me to that tweener space: hence this effort to come up with something, anything, to post on Substack every Monday.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. I wrote a novel after I graduated from college. I wrote urgently, at breakneck speed, like I was trying to save my life. This because I had somehow convinced myself that publishing a big-splash novel was my last, best chance to avoid working some stultifying corporate job in an office building for the next forty+ years. With this irrational fear propelling me forward, I finished that first novel, In Defense of Cactus Kelly, in barely over a year, and not long after I had signed with a very enthusiastic literary agent. Around this time I remember Kate saying, on one of our many hours-long long-distance (212)-to-(617) phone calls: “So that’s it, then. Right? It’s happening for you?”

Wrong. That agent asked me for a second draft, and when she got it she became a whole let less enthusiastic and fired me.

There’s an episode of The Simpsons where Jimbo, one of Springfield’s teen delinquents, tells Homer:

You let me down, man. Now I don’t believe in nothin’ no more. I’m goin’ to law school.

Lots of Simpsons lines stick with lots of people for lots of reasons. That one sticks with me.

Two years later I had Jimboed up and was going to law school—starting my first year. I had leased a dreary one-bedroom apartment on Elmer Street in Cambridge, and amid all the classroom commitments and trumped-up 1L drama a familiar desperation was taking hold: If you’re not careful—if you don’t stand and fight—they’re going to stop you from writing. “They” being who? Well, everyone: law profs, federal lenders, Jekyll-and-Hyde literary agents and the soulless editors they served, anyone who stood for and enabled The System.

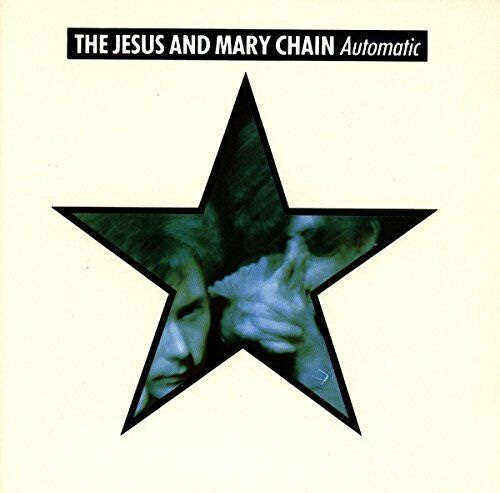

I don’t know where the Turnpike Witch came from. Except kinda sorta I do, because one night when I was caged up in Elmer Street, with Torts and Civil Procedure set aside for the night, I was stewing, and I had the Jesus & Mary Chain loaded in the CD player. Their third album, Automatic. Track 1 is called “Here Comes Alice” (Apple Music, Spotify). I listened to it play through, something clicked with the song lyrics, and suddenly I had an idea of a character. I got into the chair (always the hardest part), opened a blank Word file (always the second hardest), and I started to type. My fingers were on fire. Neurologists will tell you that a reflexive motion happens at double-speed because the stimulus-response arc goes only as far as the spinal cord, cutting out the brain entirely. My brain may have been involved in the writing that night, but likely as not it was only the fingers, hands, arms, and spinal cord doing the work. Which would explain why I remember so little of what was happening.

The song worked on me at a level somewhere between the conscious and the subliminal. (Liminal, maybe?) Because let’s be clear: nothing about “Here Comes Alice” describes a serial criminal performance artist in traffic. Last night I Googled the song’s lyrics and read them, top to bottom, for the first time. It doesn’t take any genius-level exegesis to figure out that the Alice character Jim Reid is singing about is a drug dealer. Heroin, most likely, in the grand lyrical tradition of the Velvet Underground. But that’s not where my mind went with Jim’s lines:

Here she comes, walking down the street. The street? The New Jersey Turnpike, obviously!

The heat sticks to summer’s heavy sweat. Hang around, it’ll get hotter yet. The cops are coming. Alice needs to finish her performance and get the hell out of the road.

You got the shakes and it’s gonna get worse. Don’t you know it’s all a part of the curse? This is Alice talking to herself. She shouldn’t be back on stage—not so soon after the disaster last time. But this is the cost of celebrity: the people want more of you than you can give.

She’s got the hit that takes you into space … You couldn’t guess that she could take you that far. She is a shooting star, this Turnpike Witch. Burning bright, carrying us all off with her as she streaks across the sky.

Get your lips ’round a cool black Pepsi Coke. What to do with this? Ooh: I know. A subplot where guerrilla marketers leave empty Pepsi bottles at the scenes of the Witch’s crimes—to Alice’s great irritation, because she drinks Coke.

Uhhhhh, okay.

Three hours later, I had a first draft of a first chapter of what would ultimately become New Jersey’s Famous Turnpike Witch. Section header in boldface type at the top of the Word .doc: Here Comes Alice. This origin story of course means next to nothing to anybody. Unpublished person who sometimes writes, and all that. But aside from the most important things—my marriage, raising children, that time in college when I “ate for the cycle” at McDonalds: cheeseburger, double cheeseburger, triple cheeseburger, Big Mac—this novel is the best and most important thing I’ve ever done. And I will fight anyone who tries to tell me otherwise.

Looking back, I might have done better if I had taken Jim Reid’s cue and made Alice a simple drug dealer. Over the years I have sent hundreds of query letters into the void, eliciting next to no interest. While I was writing NJFTPW, I signed with a second, then a third literary agent for In Defense of Cactus Kelly. I think my plan was to break through with that first, more conventional book—soften up the reader base a fair bit, so they’d be ready for a full-on meandering cock-and-bull story about a sociopath in an orange balaclava who sprays Cheetos up and down the New Jersey Turnpike, to the delight of her hundreds of adoring fans colonizing the rest stops. Never mind that the book is 100,000 words long, or that it is not sci-fi or chick lit or fantasy or erotica or young adult vampire fiction or B Is for Bullshit, and therefore entirely without any discernible market that might attract the interest of an agent, much less anyone in a publishing house. If My Bloody Valentine could get away with Loveless, there had to be room in the literary world for me. Right?

Wrong. From time to time I am asked why I don’t write books that more people are predisposed to like. Honestly, I don’t know what to do with that question. It’s not that I’m stubborn. I was never actively trying to submarine a literary career so that I could tell people at dinner parties I’m an attorney. These really are my best efforts. I suppose I could get in the chair and try my hand at writing spy novels, Department of Defense thrillers for men my age. But would my arms catch fire like they did back in that Elmer Street apartment in 1998? If I actually had to involve my brain in the process, how hard would it have to work in order to produce something convincing? Where, too, does the heart fit into all this? I write fiction, yes, but I don’t lie well. There comes a point where I may as well be writing a legal brief.

Speaking of, I was out of law school and working at a midsize firm, meeting with clients at a pharmaceutical company in Delaware—because of course I was—when I got the email from my third and final literary agent, informing me he had been admitted into a Ph.D. program in Anthropology and was quitting the business. He expressed his regret that he hadn’t managed to place Cactus Kelly with a publisher, and he wished me the best of luck finishing Turnpike Witch. This was the kill shot. Ted was, and I assume still is, a lovely and thoughtful person who actually got me as a writer. No surprise, then, that he felt compelled to find a different line of work.

Every five to ten years I go back to New Jersey’s Famous Turnpike Witch. I expect I’ll be disappointed in it—I’ll have outgrown it, or I’ll find the writing too loose and undisciplined for a lawyer in his third decade of practice. Turns out I’m never disappointed in what I find there, and sometimes I even get wound up enough about it to send out more query letters. Writing, including fiction, is at bottom communication, so you’d think writing can’t survive without an active readership. But then those query letters return the same patronizing rejections as before, and I wonder if it might just be enough for a person who sometimes writes to have communicated with a later iteration of himself—a person who sometimes reads, maybe, and appreciates the writing.

This is my long way round to thanking the Jesus & Mary Chain for “Here Comes Alice.” It was the spark that touched off everything that followed—the hit that took me into space.

I’ve got nothing, but I rode on a star. I couldn’t have guessed that she could take me this far.

There are many indie publishers who accept manuscripts without agents.

If not now, when.......