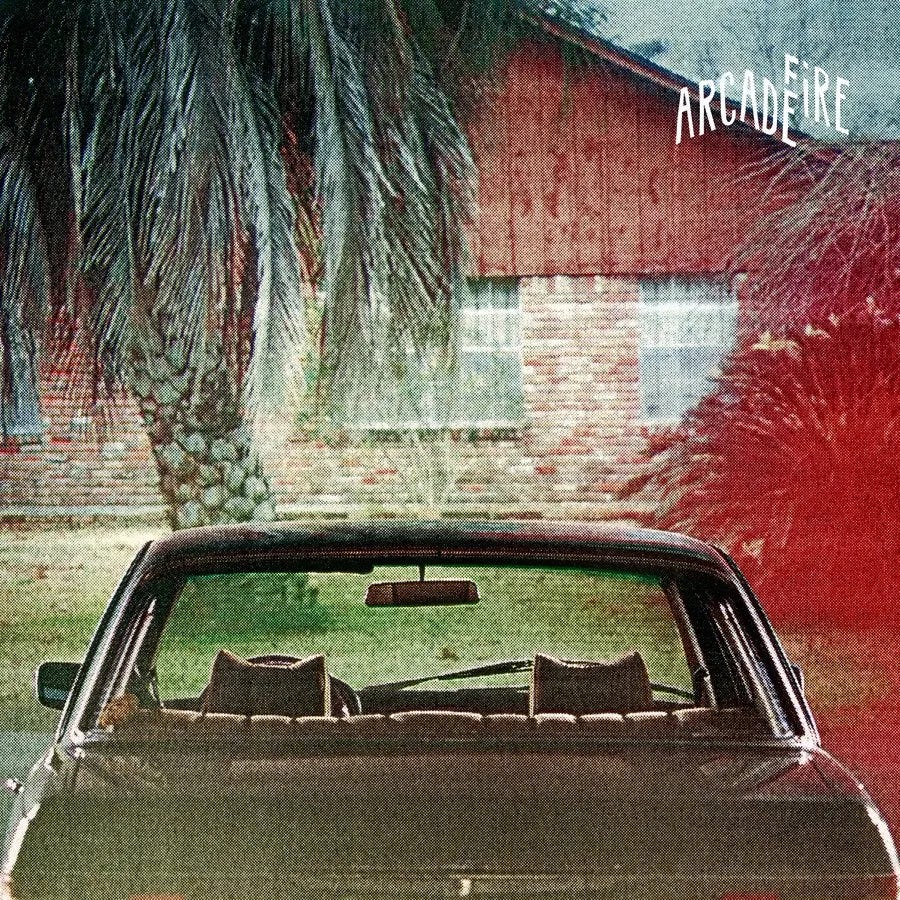

Arcade Fire, "Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains)"

“Dancing Queen” sucks. It’s probably the 30th-best ABBA song. There is very little about it that is worthy of close attention. Its melodies—and to be fair, there are several—are pretty in the same way deodorant smells good: they strive for nothing more than to take non-pretty away. The song’s buildup is glacially slow. I could get a pizza delivered to my headphones—maybe even deep-dish—before the “payoff” ever gets there. And the lyrical content is positively stultifying. There’s a reason why they couldn’t work this song into the Mamma Mia! musical, other than in the encore. It’s a song about nothing, and not in the good, Seinfeld way.

By contrast, each of “Knowing Me, Knowing You” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Take a Chance on Me” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Hey Hey Helen” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Gimme Gimme Gimme” (Apple Music, Spotify), “S.O.S.” (Apple Music, Spotify), and—can you hear the drums?—“Fernando” (Apple Music, Spotify) displays something new and rewarding from, and about, Agnitha, Benny, Björn, and Anni-Frid. But do we hear any of these songs at a wedding reception?

No, because without fail, “Dancing Queen” is the song the deejay pulls out from the diverse and compositionally masterful collection of ABBA’s work. And without fail—or for that matter any critical examination of the question—the crowd always responds ecstatically. That dumb coordinated dance with the diagonal pointing follows, and I’m gone. I’m off the dance floor, beelining to the bar.

This may sound cynical and contrarian, but I don’t think it is. In my heart of hearts I’m an idealist, or at least a hopeful sort (see “Hang on Sloopy”), and that very idealism inclines me to believe that most people don’t actually think “Dancing Queen” is a good song on the merits. They celebrate it instead for symbolic reasons. It stands for a place and time wherein the music was, for the most part, pretty lousy—and the associated behaviors, whether on the dance floor or in nearby bathroom stalls, were culturally vacant. We didn’t ourselves have to live through the terrors and indignities of the Disco Era. But when the needle drops on “Dancing Queen,” each of us is afforded three minutes and fifty-one seconds to act as cheesy and ridiculous as their imagination and soft tissues will allow. The song affords us a brief vacation from our more enlightened age—or to borrow a phrase from Johnny Rotten and the Situationists: “A cheap holiday in other people’s misery” (Apple Music, Spotify).

I’m picking on weddings here (and disco), but the truth is that too many of the big events and moments in our lives have succumbed to the “First, Do No Harm” principle, when it comes to soundtracking. I’m writing this post two days after Sinéad O’Connor died, when too much of what anyone wants to talk about is the incident with the Pope’s photograph on Saturday Night Live. This was a television show that aired in the wee hours and from the jump had prided itself in pushing boundaries. But by the early 1990s it was largely domesticated, a sandbox for at best moderately challenging ideas that could appeal to a critical mass of at least half the viewing public. And sadly, it became an object lesson for our cultural gatekeepers: do whatever you have to do to keep something like THAT from happening again.

It’s a fact of life, though, that the more interesting and substantive an instance of content is, the more likely it is to turn or piss someone off. And the larger and more diverse an audience is, the more likely it is to include one or more folks who are ripe for triggering. Hence, Muzak: everybody in the elevator harbors a low-level disdain for it—“wouldn’t choose it for a playlist,” they’ll say—but no particular person actively hates it. No one breaks out into hives over it. And this is what the folks framing Our Elevator Experience are aiming for: just something soft to fill in the space. And that’s just fine for elevators, which after all are close quarters we’re sharing with strangers, trying to will a door to open with our eyes. It’s an awkward situation for everybody. We can stand to hold back on the Norwegian black metal here.

But then the elevator door opens, and we step out into the reception hall, prime time network TV programming, or the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and the sharp corners are sanded down there, too. The messaging is about as bland, and broadly inoffensive remains the order of the day. Two years ago my baseball team announced its plans to change its name to the “Cleveland Guardians.” By that time I had long since come around to accepting that the Indians branding had to go. But the Guardians name signifies next to nothing. What exactly does a guardian do, outside of the legal context? It guards, to be sure, but what (or whom) does it guard, against what (or whom), with what, and how? What does a guardian look like? Ask ten people to draw one, and you’ll get ten different pictures.

Here’s an email I wrote to friends on July 23, 2021, just after the announcement:

This is pathetic. It’s elevator-music, Regis & Kathie Lee, Super Bowl halftime show, make-no-waves branding. It’s soulless, meaningless, vacuous, milquetoast crap. And of course Tom Hanks and the Black Keys feature in the reveal video, because the Dave Matthews Band and Ray Romano don’t have Cleveland ties. And this trumped-up “we stand together to protect” rhetoric is positively gag-worthy. It’s a three-lines-of-code, write-a-lazy-speech algorithm set to late-era Springsteen. It convinces me of nothing.

There’s a bridge no one cares about, with statues on it that are moderately Art Deco. The statues are Guardians of Transportation, we’re told. And suddenly, that’s your inspiration for this team’s identity. There are a shitload more Spiders on that bridge than there are Guardians, I can tell you. And I bet a fair number of Cormorants fly over and shit on those Guardians every day.

This was a twenty-yard shanked punt on third down. Or more to the point: a bunt in the home-half of the tenth, with the team down a run. Paul Dolan plays not to lose, and this is what we get.

In my defense, I was in the middle of a breakthrough case of COVID-19 when I wrote that message, and I had been on Team Spiders from the jump. In the time since, I have calmed down, and I can appreciate now that of course the team’s ownership was “playing not to lose.” Half of the fan base was already seething over the change away from Indians. And a sports team’s fan base doesn’t hew to any particular taste-based demographic: it’s just a handful of area codes stitched together around a stadium. It has rock fans and hip hop fans and country music fans and Republicans and Democrats and independents and auto workers and lawyers and hairdressers and cops in it. So if you’re hearing from even 20% of your customers that they think “spiders are icky,” then yeah: you chuck that option out the window.

I understand all this. I really do. I just wish the world worked differently. There are six billion of us running roughshod over the planet right about now, and the upside of this, as against the environmental catastrophe, is that every one of that six billion brings a unique and distinctive blend of perspective, interest, ideas, talent, and life experience into the soup. By way of example, there is—and will only ever be—one person who could do this:

Six billion different colors: so many more than the human eye can ever see in one lifetime. So why in the hell do nameless, faceless forces require us to spend so much of our lives looking at the same shade of beige? And that’s really it. When I stomp off the dance floor during “Dancing Queen,” when I’m dashing off over-the-top rants about my baseball team’s unimaginative ownership, (I feel like) I’m fighting my one-man war against beige. That’s not cynicism—it’s idealism.

And really: how hard is it to get stuff like this right? Back in 1997 I was watching a playoff baseball game, and Jim Thome hit an important home run for my then-Indians. At the end of the inning, the network—I think it was NBC, with Bobs Costas and Uecker on the call—showed a replay of Thome rounding the bases, with Bowie’s “‘Heroes’” (Apple Music, Spotify) playing in the background. This wasn’t some paid promotion from the record company like we have today, where it’s agreed over cigars and Sambuca shots that national audiences will be hearing Fall Out Boy every time ESPN cuts to commercial, for the duration of the college football season. On that day Jim Thome was a hero, and NBC went out and picked the best possible song to say so.

So let’s bring back that sensibility. For decades now “Rock ‘n’ Roll Part I” and “Who Let the Dogs Out?” have been deployed ad nauseam to fire up stadium and arena crowds. What if we gave Gary Glitter and the Baha Men a break and tried Neu!’s “Super” (Apple Music, YouTube) instead? There would be a learning curve, sure: more would be asked of the attendees than a single HEY or series of WHOs. But it is not too much to ask Americans to learn and time up Klaus Dinger’s various whoops, grunts, and squawks. Our children can commit Eminem’s five gears of lyrics to memory, after all, just as we mastered “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” (Apple Music, Spotify) back in our day. The sky is the limit here: we just have to reach for it.1

As for weddings, I propose we substitute out “Dancing Queen” in favor of “Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains)” (Apple Music, Spotify). It’s a mid-tempo tune, and anyone who’s been to an Arcade Fire show can tell you it plays exceptionally well under the disco ball.

I can’t confirm that Montreal’s Finest were aiming to rescue us all from “Dancing Queen” when they conceived and delivered “Sprawl II.” But it sure seems like it. The core principles of these songs are the same, and Arcade Fire straight-up copies their disco drumbeat from ABBA. But from here on up the protocol stack, Arcade Fire brings something bigger, better, and more daring at every level. The bass is a whomping thick liminal blanket, half-heard and half-felt. Synths pile over synths piling over synths: every one of them shimmers differently, and not one of them isn’t necessary. Thirty years of techno-musical progress have never been so apparent as they are here.

Regine Chassagne’s vocals are the icing on this hundred-layer cake. And it shouldn’t surprise anyone that she has a word or two to say about the dumbing-down of The Culture …

They heard me singing and they told me to stop: “Quit these pretentious things and just punch the clock.”

… or for that matter about what we—not you and me, but the Everyone We, at the level where decisions are made about what the world has to look like—have done to litter the landscape with cut-and-paste jobs of empty, familiar things, with apparently no higher ambition than the dogged pursuit of comfort and convenience:

Sometimes I wonder if the world’s so small, that we can never get away from The Sprawl. Dead shopping malls rise like mountains beyond mountains, and there’s no end in sight. I need the darkness: would you please cut the lights.

Two weeks ago my daughter and I were listening to “Sprawl II,” as I was driving south on I-95 past the Burlington Mall and all the chain restaurants bracing the highway. It was late in the evening, and the long curving road stretched out ahead of us, a dual stream of red taillights and white lights from the cars heading north. For five and a half minutes, everything we saw—every Dodge Neon, every highway reflector and overpass—was a good 30% brighter and clearer than before Lila cued up that song.

Now imagine what this track could do for a wedding.

As for “We Will Rock You” (Apple Music, Spotify) and “Seven Nation Army” (Apple Music, Spotify), we can leave these right where they are. Not all of the settled answers are wrong.