Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers, "Government Center"

For a while now I’ve had Jonathan Richman in my hopper, and it was just a question of when. I got started Friday on an altogether different idea, but it bore out that my thoughts on that subject were all kinds of muddled, so that at the very least I would need to sleep on that post, if not postpone it outright to another Monday. So I chucked it and ate a carton of Chinese spare ribs, watched the Guardos on TV, and went to bed.

Lately I don’t get out of bed without doing at least half the New York Times crossword on my phone. When I woke up Saturday morning, the answer to 13-Across was LESBIAN BAR (Apple Music, Spotify). Signs like this you ignore at your peril. Jonathan it is.

Kate and I first saw Jonathan Richman at the Somerville Theatre in Davis Square on June 14, 2000. Evan Dando opened. We’d been married for almost three months … Kate and I, that is: Evan wasn’t involved. Kate’s not a big live music fan, but if Jonathan is in town, she’ll go, because he meets all her requirements. She loves the music and finds him adorable. In addition to performing, he entertains, and always in small, comfortable venues. For a person who has asked, “Why would I take the trouble of going to a concert when I can listen to the music at home and pick the songs for myself?”—and yes, she spoke those words out loud, to my face—Jonathan Richman is as much of a sure thing as it gets.

So sure, in fact, that based solely on a descriptive recommendation of The Jonathan Richman Experience from a work colleague the summer before, I bought us two tickets for that June 2000 show without telling her about it.

Acting without consulting Kate is not something I typically do. Just last week I was waiting at the gate on a flight back home from Cleveland. It was a full flight, one of the seats on the plane had broken, and they were soliciting a volunteer to give up their reservation and fly later. Delta was offering $1500 plus comped lodging and meals for the night. The Guardians had another home game later that day, and I already had a ticket, because I’d bought the standing-room monthly pass for April. The $1500 cash would more than pay for my entire trip.

So what did I do? I texted Kate for her input, and when she didn’t immediately answer, I called her. Her answer? Of course you take the $1500. I don’t need you back here tonight. Now I might have guessed this, but I didn’t want to lone-wolf the decision. And so it went that by the time I hung up, another passenger had moved in on the gate desk and taken the deal out from under me. Case in point: acting without consulting Kate is just not something I ever do.

But some earlier, more licentious version of me did exactly that in June 2000. I read about the concert listing, bought the tix, and announced to my wife with uncharacteristic authority, Leave the evening of June 14 open, because I’ve made plans. Which she was happy to do, because—and she says this a lot—she actually likes it when I show initiative and make confident decisions. I don’t know why that should be, but it might be that for her it’s a dazzling, spine-straightening event like watching an eclipse. Anyway.

An important thing to know about Kate is that she is in fact hard to surprise with anything, because she’s a bit of a snoop. Just you try and get a package delivered to the house and safely stowed away during holiday season, without her getting her fingerprints all over it first. She has all kinds of excuses for all this poking around, but don’t buy any of them. I’m told by her father and brother that this sort of, um, curiosity goes way back. I bring all this up now because on the afternoon of June 14, 2000 Kate called me at work and said, “I know where we’re going tonight.”

At the time I was a summer associate at a law firm in Boston. Now a brief word about summer associates for readers who didn’t go to law school or hang with anyone who did: most students accept a summer job with a firm after their second year. This is part of a longer-term hiring process. The summer gig, while generally pretty cushy—firm-sponsored trips to Fenway, booze cruises, etc.—is basically a ten-week audition for a permanent gig coming out of law school a year later. So when I say Kate called me at work, I’m saying she called my office line at Bromberg & Sunstein LLP downtown, in the summer after my 2L year, when from to time I might actually have been working.

When Kate told me she’d cracked the code on my plans, my first thought was that she actually had figured out we were going to see Jonathan Richman. She’d gone rummaging on Google to see what was happening in town that night, and parked right there in the search results, plucking at his guitar, was I, Jonathan. My second thought, which came to me hard on the heels of the first, was that in fact she might not have cracked the code, because the Cure was in town, too, that night.

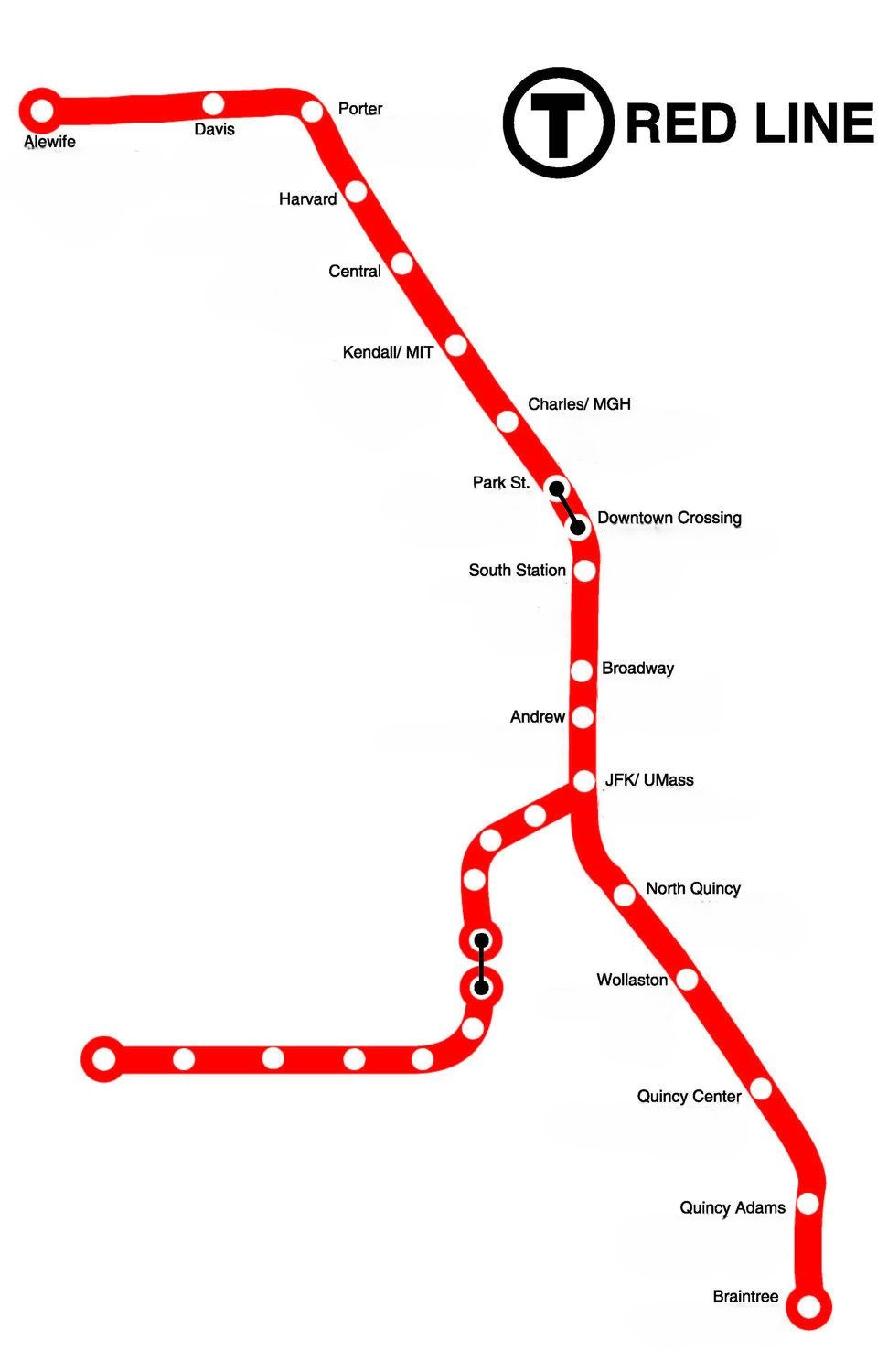

Betting on the possibility that my second thought was the right one, I took a shot: Aw, you caught me, I said. Well, I gambled a bit here, because I wasn’t sure you were still interested in the Cure. And Kate said yes, she was: she was really excited to go to the show. Which, given what I wrote before about her longstanding attitude toward live music, may have been more polite than true. We wrapped up the call, I finished my work day, then I took the Red Line train outbound to Cambridge to meet Kate back at the apartment. During the commute I gave some more thought to the fact that my wife was convinced—and I had confirmed—we were going to see the Cure, and I decided:

I’m gonna see how far I can push this.

Now I’ve told this story a few times over the years, and in every rendition of it, the Cure were booked to play at the Garden downtown. You know, the Garden, where the Bruins and Celtics play. But the thing is, when I write these posts, I go online looking for documentary evidence supporting my story, and often as not, there’s some daylight between what I’ve remembered and what actually happened, per the public record. And right now I’m seeing that the Cure did not play the Garden on June 14, 2000. They played down the road at Great Woods.1

This distinction matters, because to get to the Somerville Theatre, we needed to walk to Central Square and take the outbound Red Line MBTA train to Davis Square. By contrast, we would have had to drive to Great Woods, which is down by Foxboro. So at some point before we left the apartment I must have represented to Kate—wrongly, maliciously—that the Cure show that night was happening at the Garden: i.e., Red Line inbound to Downtown Crossing, Orange Line from there to North Station. I don’t remember this second bluff, but presumably it worked, because off we walked up Western Avenue toward the Red Line train, without any further questions.

When we got to Central Square, I turned toward the outbound platform, because I knew we were going to see Jonathan Richman. Kate pulled up short and questioned me: “What are you doing? We need to go inbound.”—because as far as she knew, we were going to see the Cure. And again, on the Let’s see how far I can push this principle, I thought up a lie and I thought it up quick:

“Um, yeah: I forgot to tell you. I need to go into Davis Square.”

“Why?”

“Um, for work. They need to me to pick up some documents. Too sensitive to send by courier.”

“Tonight?”

“Yeah. That’s the only time the guy was available.”

Kate sighed. We got on the outbound train. It’s three stops from Central to Porter. Here’s a map, for your reference:

During the course of the ride, she grilled me:

Q. What are the documents for? A. Some litigation matter. I didn’t get the details.

Q. Where are you picking them up? A. Not sure. They gave me an address, but I lost it. I think I can find the building, though.

Q. You’re just going to bring these documents with you to the concert? A. Yeah. I hope it’s not a lot of them.

Giving these answers was simultaneously fun and effective. Fun because I was absolutely messing with her. This wasn’t my first objective—it’s more of the truth to say I was lying on the fly, I’m not a good liar, and I lacked both the creativity in the moment to give better answers and the confidence I wouldn’t get tripped up on the details. The lies were effective because they played to type, at least for this 2000 version of Kate’s husband:

Just like him to get roped into some dumb document delivery on a planned night out, then lose the pickup address. And what’s his plan for getting through Garden security carrying a banker’s box of files?

All of these objections Kate swallowed down for the duration of the ride to Davis. We rode the escalators up to street level in silence, and as we passed through the station doors, I pointed in the direction of venue and said, “It’s this way, I think.”

“You think.”

“Yeah.”

That was enough to get us down the street, with the Somerville Theatre marquee in our sightline. Kate looked up at it.

“Hey, look,” she said. “Jonathan Richman is coming.” Then her face fell. “Oh, but it’s tonight.”

“Aw, man,” I said. Let’s keep pushing this. “That sucks. Would have been great to go to that show.”

And because Kate is who she is—lovely, thoughtful, generous—she turned on a dime: “Oh, that’s okay. I’m really excited to go this Cure concert!” At the Garden. With a bajillion other people. Playing songs off a record she didn’t know. If we even got there, with this mystery document errand hanging over the evening.

At that point, I stopped pushing. “Well that sucks for you,” I said, “because we’re going to see Jonathan Richman.” I fished the tickets out of my pocket, a big smile broke across her face, and we walked into the venue. As always, Jonathan was nothing short of delightful that night: unrelentingly upbeat, tickling melodies out of his guitar, offering needless words of encouragement to his forever sidekick, Tommy Larkins, on the stand-up drum kit. And as always, he sang in multiple languages, swiveled his hips, embarked on one or more of his trademarked extended solo dance routines—taking care at all times to hold his guitar out of harm’s way—and in the process he brought unalloyed joy to every one of us in the crowd.

I can’t find any YouTube footage from that show, but here’s a gig in Japan from around the same time:

Two years after that show in Somerville, almost to the day, Kate and I drove to Providence to see Jonathan a second time. The show was at Lupo’s downtown, on a Saturday night. I’m thinking we must have had some printout from MapQuest to get us there. When we arrived, we circled the block looking for parking, and we found a lot just around the corner from the venue. When we pulled in, there was a man standing by himself in the corner of the lot. Depending on your point of view, he was either minding his business or loitering, but something about his bearing gave Kate the creeps.

“Let’s park over on the other side,” she said, and I didn’t disagree. As I swung the car around, the man passed across our headlights.

“Kate,” I said. “That’s Jonathan Richman.”

“Oh my God, it is!”

We had a good laugh about that. Car parked, we got out. “Jonathan, how are you?”

“I’m good, I’m good. You go on inside. I’m coming.” We watched him cross the lot toward a beat-up vintage Mercedes Benz with California plates. Earlier that day I had read that Jonathan, a native New Englander—see, e.g., the Modern Lovers’ references to Route 128 and the Mass Pike in “Road Runner” (Apple Music, Spotify)—was living in the Bay Area. So that tracked. He popped open the trunk and began rummaging around in it.

Not long afterward Kate and I were inside the venue, standing a short distance from the stage, when the front door opened. Jonathan walked in with his guitar slung behind his back. The smallish crowd cheered. Folks patted him on the shoulder as he walked by. Then he climbed up on the stage and started to play. No green room, no backstage, no let’s turn down the lights and play the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey over the PA—nothing. He just came in through the front door, like everybody else. And right on time, too.

What I’ve always wondered about Jonathan Richman is who he is when he’s at home. Is he perennially positive, to the point of goofy-silly? When he wakes up in the morning, does he jump out of bed and happy-dance into the bathroom to brush his teeth? When the smoke alarm goes off in the middle of the night, does he just shrug it off and smile? Of course the answer to all these questions has to be no. No single person can be as real-life joyful as Jonathan’s stage persona suggests.

For that matter, that persona is constructed and rendered with a level of artifice that has at least me asking whether there isn’t a wicked and biting sarcasm underneath it. The vocal affectations—parked somewhere between 1920s New England and California surfer—his start-stop sentences, odd lyrical rhyming excursions, and scripted in-song interjections: he was doing this schtick as early as the mid-1970s with the Modern Lovers. And a fair bit of the work on their ’76 self-titled record had some real edge to it:

Pablo Picasso never got called an asshole. Not like you. (Apple Music, Spotify)

It didn’t take long for Jonathan to put that kind of negativity behind him. A year later, he couldn’t even bring himself to slag off his piece-of-junk “Dodge Veg-O-Matic” (Apple Music, Spotify):

Dump truck, dump truck, spare that car. Don’t you know how find it are?

By then it was off to the races: serenading the “Ice Cream Man” (Apple Music, Spotify), rising to the defense of an “Abominable Snowman in the Supermarket” (Apple Music, Spotify), and rallying his band downtown to play “Government Center” (Apple Music, Spotify), because Boston’s bureaucrats need love, too:

We got a lotta lotta hard work today—we gotta rock at the Government Center, to make the secretaries feel better, when they put the stamps on the letter.

Not so much preaching, but modeling peace, love, tolerance, care, and above all joy at a time in rock ‘n’ roll when it was positively gauche not to hate literally everything. This might have been a case of shrewd marketing—zigging when others were zagging—but almost a half-century later, Jonathan is still committed to the bit.

Probably I’m cynical, but I’m inclined to believe that the aesthetic of the Modern Lovers, then Jonathan Richman & the Modern Lovers, and now Jonathan Richman is really just the continuation of cultural criticism by other means. If we’re to derive any broad, overarching theme from what we see at a Jonathan Richman show, it’s that he’s stating the cases for community and understanding. Or put differently, unless somebody steps up, Mr. Softee won’t ever get his due, all the Karens out there will drive the Yetis out of Whole Foods, and the admins in state government will continue to toil in quiet desperation under their buzzing fluorescent lamps.

What does it say, then, that all of us out in the crowd are moved to laughter by The Jonathan Experience? Do we laugh because he’s just plain goofy and fun? Are we laughing at a simpleton whose sensibilities are so far removed from what we understand to be reality? Or are we laughing because of the awkwardness of the moment—because he’s showing us up? Certainly it’s some combination of the three.

Many, many songs to choose from here, but since I spent so much of the first half of this post talking about MBTA stops, let’s go with “Government Center.”2

Setlist.fm advises that Great Woods was called the “Tweeter Center” in those days. Don’t ask me to keep track of this shit. The truth is, that venue hasn’t been called “Great Woods” in a quarter-century, but that’s the name everyone in Boston uses, because in addition to providing advertising for paid sponsors, names also serve the secondary purpose of persistently identifying the signified object, so that we can effectively use language to communicate to others where the hell the show is.

When I looked this track up on the streamers so I could grab links, I saw it listed as a bonus track on that first Modern Lovers album. That’s an earlier, altogether different arrangement from the one I linked in the main text—and one I never heard before today. It’s an interesting listen. You can definitely hear licks of Lou Reed in Jonathan’s vocals: as you might expect from a Velvets-obsessed pilgrim who slept on their manager’s couch as a teenager. In any case, here’s that Modern Lovers’ version (Apple Music, Spotify).