Joy Division, "Atmosphere"

If you came of age Stateside in the 1980s and you got into Joy Division, you probably found your way back to them through New Order. And you would have heard New Order first on the Pretty in Pink soundtrack in 1986. All of us who grew up with MTV and were especially drawn to the new wave acts—Modern English, Madness, Howard Jones—either bought Pretty in Pink on cassette or dubbed it from someone who did. At some point I’ll write a post about John Hughes movies and the bands they turned us onto. The relevant one today is New Order. “Shellshock” (Apple Music, Spotify) claimed six-plus minutes on the cassette and was what turned so many of us on to New Order. Then a year or two later, after you dug deeper into their catalog, you would realize Hughes had also deployed their instrumental “Elegia” (Apple Music, Spotify) to great effect in the movie:

“Shellshock” was an absolute banger, with a dozen layered tracks and a hundred effects, power chords, jackhammer drum programming, and an occasional Latin break to lower the intensity, so you didn’t get completely carried away.

It’s never enough until your heart stops beating.

Off you went to the record store to find more of this sound, and waiting for you in the N section was Substance, New Order’s 1987 hits-and-mixes compilation. “Shellshock” was on it—the very same mix from Pretty in Pink, as it turned out—so you could be assured of at least one familiar song. In those days you were on a tight budget, and buying an album “sight unseen” was risky. You wanted to have enough of a foothold into the track list to be confident you weren’t blowing two weeks’ lawn-mowing money on a dud record.

Substance didn’t disappoint in the least. Worth every penny when I bought it on cassette, then again on CD a few years later, with the bonus disc carrying additional remixes and B-sides. There’s no further new material on the vinyl reissue they just put out, but I’ll probably end up buying that, too. I don’t mow lawns anymore—not even my own.1

Among Substance’s many delights were a re-recording of “Temptation” (Apple Music, Spotify), the full 12-inch mix of “Blue Monday” (Apple Music, Spotify), which was probably the most consequential dance track of the decade, and “Bizarre Love Triangle” (Apple Music, Spotify), another celebrated Euro-disco number that I remember dancing to on the Carla Costa ocean liner in ’88 along with Zio, my sister, and my cousin Marlene. The extended family was on a Caribbean cruise to celebrate my grandparents’ 50th anniversary. Costa was—still is, I think—an Italian line catering largely to Italian tourists. I was pushing fifteen and in love with about eleven different girls in the ship’s discotheque that night, all of whom were in their twenties, didn’t speak English, and probably never laid eyes on me anyway. “Hopeless Love Dodecagon” would have been more a more appropriate track to throw down to.

Anyway.

As far back as eighth grade I was the sort of listener who wanted to learn more about what I was hearing. Who’s playing this? Where are they from? What’s their story? Surely it was MTV that stoked and provoked this curiosity. Music videos usually showed you what the artists looked like, then maybe Martha Quinn came along to tell you a bit more of their story on MTV News. But I hadn’t seen a New Order video. All I had on them was what I held in my hands: i.e., a cassette box with liner notes in it. The front cover was black text on a white background: New Order — Substance 1987. The credits didn’t offer much more information. All songs written and produced by New Order, except where otherwise noted. The bland names of English men listed as producers and sound engineers. Martin Hannett, John Robie, Stephen Hague.

The liner notes did say that the first track on the first side, “Ceremony” (Apple Music, Spotify), was written by Joy Division. That was an interesting datum, especially given that “Ceremony” sounded so different from the rest of the tape: light years away from the ice-cold early ’80s synth rock of “Blue Monday,” and no closer for that matter to the hotter and thicker gonna make you sweat dance beats on Side B of the cassette. “Ceremony” was melancholy guitar rock, holding more in common with early Smiths than a song like “BLT.” And somebody/ something called Joy Division wrote it. This only begged more questions. Why did this song sound so different from the others? Was it a cover?

I went looking for Joy Division at the record store. No dice. A minute ago I went into Discogs and was able to confirm that the two Joy Division studio records, Unknown Pleasures and Closer, were never released in the U.S. on cassette. They wouldn’t come out on CD until 1989. This was yet another instance where the kid in Ohio follows a trail of bread crumbs to National Record Mart and hits a brick wall.

At some point around this time I did become aware that Joy Division was New Order before it became New Order. That is, New Order’s members were in a band called Joy Division until that group’s lead vocalist died by suicide. Other scraps of information were available, including that their last, most celebrated single was called “Love Will Tear Us Apart” (Apple Music, Spotify) and the name Joy Division was taken from the name the Nazis gave to the section of the concentration camps where they kept women as sex slaves. All this was pretty heavy, and as far as I can figure I probably read all this in Rolling Stone, or more likely, SPIN, which always gave more time and attention to the alt-rock musicians than Rolling Stone did.

It logically followed that Joy Division wrote “Ceremony,” and maybe the singer had died before they could record it. But that was all I or any of my gang could figure out. We checked in with folks at school who we thought would know more, pressed them for anything they could tell us about a band called Joy Division.2 At least one report back was that the singer hanged himself by climbing on top of a block of ice and waiting for it to melt out from under him. That was some bone-chilling stuff getting relayed in the hallways, right up there with the dog-eared copies of Flowers in the Attic (Amazon) and Helter Skelter (Amazon) forever in transit from locker to locker.

Right around the time we—or I at least—could hardly take the suspense anymore, I ran off down to the record store and found another Substance compilation on cassette, this time in the J section and credited to Joy Division. With the benefit of hindsight all this looks like a genius three-year marketing plan: (1) release the Pretty in Pink soundtrack with “Shellshock” on it in 1986; (2) release New Order, Substance in 1987 with an oblique reference to JD in the liner notes; then finally (3) put out a Joy Division Substance comp in 1988. The aforementioned “Love Will Tear Us Apart” was included on Joy Division’s Substance, fittingly as its last track, and although I hadn’t heard Note One of any of the listed songs, I damned the torpedoes and dropped the ten bucks to buy it. And just like New Order’s Substance before it, I would buy the same title on CD a few years later, so I could get hold of the seven-song “Appendix” that the tape didn’t have.

The first track was “Warsaw” (Apple Music, Spotify), and it was the angriest song in my collection this side of the Violent Femmes. Not so much for its lyrics as for Ian Curtis’s spitting vocals. Joy Division’s Substance had that guitar rock I had heard on “Ceremony,” but it sounded hollow and reverberating, as if played inside a cathedral. Like New Order’s Substance, it was arranged in chronological order, so that you could hear the band evolve from the straightforward punks who saw that famous Pistols show at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester into a subtler and more refined post-punk outfit, incorporating delay effects, equalizers, and even synthesizers.

We’re told that the aforementioned Martin Hannett inflicted Joy Division’s signature sound on the band, against their interests and to their considerable dismay, after he signed on to produce Unknown Pleasures. And the band objected to his use of electronic supplements, too, because they wanted to be nothing more than a four-piece with strings and drums. But this was also a group that first named itself Warsaw after the “Warszawa” (Apple Music, Spotify) ambient song-suite Bowie and Eno hacked together on Bowie’s Low record, using a Minimoog and Eno’s prized EMS Synthi, among other unconventional equipment. If Curtis et al. loved the second, electronic side of Low this much, they couldn’t have objected too strongly to Hannett’s innovations.

There’s no evidence to support that old saw about the block of ice. What is well-documented is that on May 18, 1980 Ian Curtis was left alone in the Macclesfield home he shared with his wife Deborah and their year-old daughter. Afflicted with ever more acute, regular, and painful epileptic seizures, and possibly torn between the temptations of stardom—many believe he had taken up with Belgian rock journalist Annik Honoré3—and his family obligations, Ian put Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, another Berlin-era LP, recorded contemporaneously with Low, on his turntable and hanged himself with the kitchen clothesline.

Context is everything, and even more so here. You can’t listen to Joy Division without that ghastly tableau at least in the back of your mind. It seems likely that Ian’s death invests the songs with their singular gravity, the very suffocating nihilism that makes the band’s output—and particularly the late-era recordings—so singular and important. But the converse makes sense, too: only someone careening toward this tragic ending could have made music like we hear on “Twenty-Four Hours” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Decades” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Dead Souls” (Apple Music, Spotify).

Just for one moment I heard somebody call. Looked beyond the day at hand: there’s nothing left at all.

Now that I’ve realized how it’s all gone wrong. Got to find some therapy: this treatment takes too long.

I don’t listen to Joy Division a lot, because I actually worry about how it could affect me. I don’t feel that way about the Smiths, about Bauhaus, the Cure or Depeche Mode or any of the other black-clad melancholic Brits who introduced me to my teenage feelings in the late 1980s. It’s just Joy Division that I handle with such care, and I figure that’s because a part of me believes it could not have been good for Ian to go out on stage and sing these songs, performing his dysfunction and desperation night after night, much as Kurt Cobain would fifteen years later. See “Burning Farm.” And if that’s right, how good is it for the listener to be steeped in it for days on end?

But this is not to say that there aren’t moments in life when the right answer isn’t to pull over in the Burger King parking lot on a dreary Wednesday morning and blast Closer over your car radio with your head against the steering wheel. Like,—I dunno—after your beloved baseball team blows a 3-1 World Series lead to the Chicago Cubs, then six days later Donald Trump is elected President of the United States.

Back in 2009 I saw Nine Inch Nails and Jane’s Addiction play together in Great Woods, and I wrote this review, which turned into a post about Joy Division more than anything else.

At some point I wish out loud that Nine Inch Nails would play its cover of “Dead Souls,” and this leads into a conversation with my friend KL about Joy Division. Well, not so much a conversation, because there is live music playing, I’m monologuing, and KL, as is his practice when he goes to concerts (even though it was not really necessary here), has installed earplugs to keep his ears from ringing afterward, so he probably hears only half of what I’m saying. Joy Division is, of course, the unattainable ideal for Nine Inch Nails. If they were contemporaries, I’d use the Mozart/Salieri analogy. Joy Division had the advantage of masterful instrumentation from creatively coequal bandmates, a brilliant producer in the studio in Martin Hannett, and genuinely nihilistic and soul-destroying lyrics. Joy Division’s recordings were groundbreaking in their production values, and yet when all Hannett’s bells and whistles were necessarily shunted aside for the band’s live performances, the band was still able to deliver the goods with an intensity, an immediacy, a desperation and menace that Nine Inch Nails can only dream of having. KL nods in agreement. I can’t say for sure he’s not patronizing me (he is, himself, an insufferable rock critic), but I gather from his body language that he won’t be taking up Nine Inch Nails’ cause against Joy Division or anyone else after this show.

There comes a point where Trent Reznor means to introduce a song that is particularly important to him. He says he locked himself away by the ocean for a period of time, ostensibly to write songs, but, he says, “what I really wanted to do was kill myself.” He has clearly crafted his presentation of the story to give it maximum rhetorical kick, but given the way he said these words, I don’t doubt his sincerity. Trent winds his way through the rest of the story—he only managed to write one song during this lowest period, and it was “The Fragile.” Then the band plays “The Fragile,” which, to me, is hardly noteworthy or compelling. Not when, ever since my rant to KL ten minutes before, I have had “Dead Souls,” “Atmosphere,” Side B of Closer, and “Love Will Tear Us Apart” on my mind. This isn’t fair, of course: Ian Curtis did commit suicide, and those songs are the very documentation of his downward spiral, which found depths Reznor, to his credit and great benefit, didn’t reach. Reason #125, then, why I’m not being fair to Nine Inch Nails in this review.

And indeed, KL told me on the phone yesterday that Nine Inch Nails shouldn’t be judged against Joy Division—it should be judged against its real musical progenitors, Psychic TV and Skinny Puppy (in his view). But I’m inclined to judge Nine Inch Nails against Joy Division for two reasons: (1) the high production values of their recordings (see above), and (2) their emphasis on interior terror (see below). Most of the “scary” acts in rock serve up a theatrical kind of “scary”: Sabbath sings about the Devil; Gene Simmons spits blood; Alice Cooper is, well, Alice Cooper. Bauhaus, too, pointed to objects, images, legends in its efforts to frighten. The theatricality of metal and Goth is enjoyable. It’s a horror show: if you’re at all scared, you’re scared smiling.

By contrast, Joy Division is the only band I can think of that is well and truly terrifying.

I can’t say this about all of my writing, but this argument aged spectacularly.

A band as consequential as Joy Division will always be greater than the sum of its parts. But what parts they were. Ian was the full package: a distinctive and challenging presence on stage with a harrowing voice and complex, thoughtful writing. We can look past all the facile rhymes Bernard Sumner served up after he stepped up as New Order’s lyricist, because he was once the source of JD’s cracking guitar sound, best heard on “No Love Lost” (Apple Music, Spotify), from Joy Division’s very first, self-funded release, An Ideal for Living. Ear. Fucking. Candy (for me). Peter Hook brought that signature twangy bass, slung low at his knees and played in the high registers. And on the kit was Stephen Morris, raised on Krautrock4, thrashing out drum tracks for tracks like “Transmission” (Apple Music, Spotify) with maximum precision and endurance. No dropped strokes here.

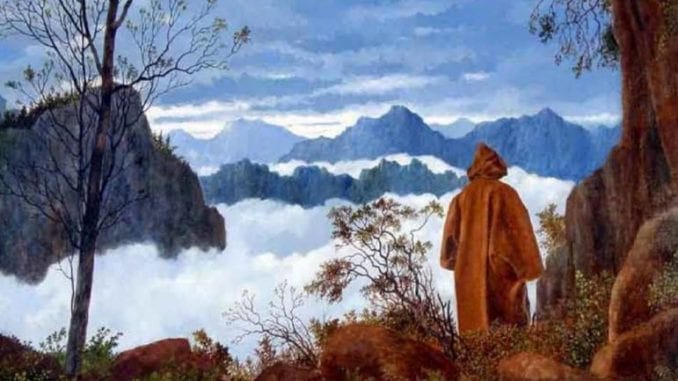

For all the high points in Joy Division’s catalog, only some of which I’ve mentioned here, one track stands head and shoulders above the others, and that’s “Atmosphere” (Apple Music, Spotify). Not the saddest, certainly, or the most beautiful—but without question the most sad-beautiful piece of music I will ever own. JD first released “Atmosphere” alongside “Dead Souls” (Apple Music, Spotify) on a two-track limited-edition EP called Licht und Blindheit (“Light and Blindness”). The publisher was a small French specialty label called Sordide Sentimental, and the image at the top of this post is the cover art for the Sordide pressing. These days original vinyl copies of Licht und Blindheit go for around $3,000 a pop. Anton Corbijn directed and produced this video for “Atmosphere” in 1988. Give it a watch, and if the spirit moves you, maybe think about buying me a copy of that Sordide Sentimental record on Discogs?

Or at least promise me this: whatever you decide, don’t walk away … in silence.

Though it would be nice if someone did.

Until her death in 2014, Annik consistently asserted that her relationship with Curtis had been platonic.

I’ve seen Stephen Morris perform exactly twice: once with New Order in 2013, and again two years ago in London, grinning ear to ear as a special invited guest of Neu!’s Michael Rother.