For four summers now we’ve been renting a cabin by Chocorua Lake in New Hampshire. The family that rents to us lets us use the dock down the hill from their house on the same property. They have a pair of kayaks and a paddleboard, among other watercraft, and I like to take a kayak out in the mornings. It’s a rare opportunity to get some cardio work done without taxing my legs, and it’s possible the rowing does some good for my old man’s upper body.

From time to time, too, I’ll take a boat out just before dusk. Rather than paddle the length of the pond, I’ll hang a right and navigate around the bend toward the dam. This is a shorter excursion, and the object isn’t to work out—it’s just a lovely way to pass a half hour on a summer evening.

I wrote an earlier post about how I default to wearing headphones wherever I go. (See “Feels So Good.”) This is as true on a kayak in New Hampshire as anywhere else, and while it’s a virtual certainty that at some point I’ll drop my phone in the lake trying to dial up a podcast or playlist, it hasn’t happened yet.

One night a few years ago—can’t remember if it was 2020 or 2021—I’d blown it. I had allowed the battery on my Bluetooth headphones to run down, so that I had to power through my otherwise delightful paddle to the dam with my ears exposed to the open air. No musical accompaniment, no exhausting preseason beat writers’ breakdown of the Buckeyes offensive line: just the sounds of nature to listen to.

About five minutes into my paddle, as I scissored my boat through the water lilies, I started singing (quietly) to myself:

Sometimes I feel like I can’t even sing. I’m very scared for this world—I’m very scared for me. Eviscerate your memory …

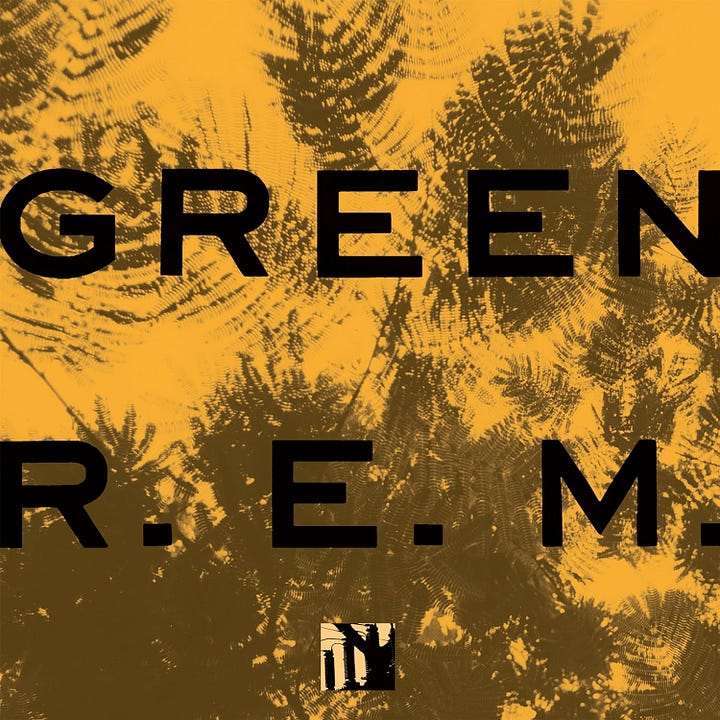

The song was R.E.M.’s “You Are the Everything” (Apple Music, Spotify). It’s a lovely composition, and I’ve had it committed to memory since Christmas Day 1988, when I found the Green album under the tree and played the cassette on repeat basically through New Year’s Day. On this song R.E.M.’s drummer Bill Berry plays the bass, bassist Mike Mills plays an accordion, guitarist Peter Buck plays the mandolin, and Michael Stipe sings. But before any of these magnificent instruments1 kicks in, you hear crickets. Dozens of them, seemingly on all sides, in stereo.

It was the crickets on Chocorua Lake that prompted me to start singing R.E.M. that night. My unconscious mind received and processed the sound of crickets chirping, matched them up with the crickets on Side A, Track 3 of Green—who I expect are an altogether different set of crickets: session crickets, probably—and almost autonomically my lips began to move and my voice box activated, so that I was singing “You Are the Everything.”

Of course this is how my brain works—and what’s more, I love that it works this way. I love that I’m essentially hard-wired to sing R.E.M. when I hear crickets.

In A Clockwork Orange Anthony Burgess wrote about this tragic paradox of the human mind: that a consciousness fashioned in God’s image, grasping at free will, should be so readily susceptible to simple, brutal mechanistic conditioning. After his arrest for rape and murder, Burgess’s protagonist is enrolled in a criminal rehabilitation program. Researchers inject him with nausea-inducing drugs and require him to watch violent and pornographic films. Through multiple rounds of these “treatments,” Alex’s brain learns to associate sex and violence with violent sickness, rendering him physically impotent in the face of his disagreeable impulses—even without the shots.

I wrote my senior thesis in college about A Clockwork Orange. Here’s what that earlier version of me wrote about the title of the book, and how Burgess deploys it to describe the human condition:

“A clockwork orange” does not connote an imposition upon the individual …, neither does it represent the unnatural and evil result of brainwashing. Instead “a clockwork orange” stands for the duality of humanity that, on one hand, renders the human will subject to brainwashing, and on the other, declares that it is immoral and criminal to do so.

I’ve carried around this sense of what it means to be human—that we’re a bumbling and awkward blend of mechanistic programming and organic aspiration—ever since I read Burgess’s book and wrote that paper. Over the years I have fretted a lot about the effect that our clockwork has on our choices. And more recently I have wondered whether we lose more than we gain, by striving to understand better how this clockwork functions. Are we each individually better equipped to resist manipulation as a result of this work, or are the scientists essentially writing operator’s manuals for our controllers?

It seems like the latter is true. Papers about the psychology of persuasion and action aren’t broadly consumed by the general population. They’re read and internalized by professionals: marketers in the best case, and in the worst, Putinist psyops contractors. There’s a reason why the teen slang Alex and his droogs speak in A Clockwork Orange borrows so heavily from Russian. “Odd bits of old rhyming slang,” one of Alex’s doctors explains, when asked about Alex’s mode of speaking. “A bit of gipsy talk, too. But most of the roots are Slav. Propaganda. Subliminal penetration.”

Still, there are times where the clockwork informs and enriches the orange. I don’t imagine R.E.M. and producer Scott Litt expected to seed crickets —> mandolin —> Eviscerate your memory associations in a generation of teenagers. But even if this were the predicted result of some master plan hatched in Athens, Georgia 35 years ago, you wouldn’t hear me complaining. So the opening of “You Are the Everything” has burrowed deep into my brain, causing me to lapse into a Michael Stipe impression whenever a critical mass of insects rub their legs together? That’s about the most benevolent deployment of behavioral conditioning I can imagine.

Let’s talk some more about R.E.M.

A few weeks ago I was talking with Florian about poetry. Earlier that day I had heard a not-so-great poem recited at a public gathering—and while the crowd in attendance applauded enthusiastically, I made eye contact with several of my friends nearby. We all crinkled our noses at the same time. The poem was fake-deep: ten inches of icing and no cake. Underneath all the flourishes, I don’t think there was any meaning at all.

Florian and I went on to talk about meaning and obliqueness in writing, and how poetry needs to have a bit of both. In my view, a poem rises or falls based on the proportions of these two active ingredients. The formula can vary—there’s no universal poetic constant here that poets must attain or approximate in their mix of meaning and obfuscation, lest they fall flat. But if the ratio is off in a particular poem, you’ll know it. And that is what makes poetry an art, not a science.

I suppose another aspect of poetry that makes it art-not-science is that a poem can engender altogether different responses across a diverse assembly of listeners (How could those people applaud that lousy poem?), while at the same time eliciting a common response among those with shared sensibilities (Oh: thank God you hated it, too. We can still be friends!)

Michael Stipe is a Grade A poet and the very definition of an artist. I haven’t to date devised a Do You Like R.E.M. Song Lyrics? litmus test for my relationships, but I feel like if I did—if, say, I selected five of my favorite Stipe tracks and required important people in my life to listen to and evaluate the poetry in them—I fully expect the people I hold the closest and find most interesting would also be the most liberal with their star ratings. I want to be clear: this isn’t a case of me declining to associate myself with people who don’t like the same bands I do. It’s not about the music or my history of it. It’s a question of poetics and their effect on you. Is your clockwork configured like mine? Let’s listen to “Driver 8” (Apple Music, Spotify) together and find out.

By now it’s a truism to say that Michael Stipe was a bit of a sphinx. He was distant and reserved and a deflector of attention, at the same time he was blistering the landscape with the contents of his brain. Like his contemporary in the Smiths (see “I Know It’s Over”), rock stardom never came naturally to him. Two centuries earlier, poets were free to install themselves in garrets and do their work with quill and inkwell, far from the madding crowd. But in the 1980s they had to stand on stages and sing, and so we were granted these two poetic geniuses, Stipe and Morrissey, awkwardly positioned behind microphones, trying to find the nerve to speak their truths into them.

Early accounts tell that at the first R.E.M. shows Michael turned his back to the crowd while he sang. At least by 1983 Stipe was front-facing, but hardly Jagger-esque. Watch him here on Late Night with David Letterman.

Knowing what we do about Michael Stipe’s stage shyness, his muted demeanor in interviews, and his tendency, at least early on, to mumble (dare I say murmur?) his lyrics, it seems reasonable to conclude that Stipe’s cryptic writing was just another protective wall he’d constructed. Our poems are ourselves, and we’re never so naked as when we’re sharing them with the world. But if we squirrel away our treasures under a mound of misdirection and code—then we’re not as vulnerable.

If it’s really the case that Michael Stipe’s poetic style was a reflection of his shyness, then we should all be thankful that rock ‘n’ roll was adaptable enough to accommodate a front man this unconventional. Consider these lines:

Swan, swan, hummingbird. Hurrah: we’re all free now. What noisy cats are we.2 Girl and dog, he bore his cross.

What can we make of this? Is it “word salad?” Did Michael subcontract this work to monkeys with typewriters? Hardly. There is much more happening here than just an intriguing juxtaposition of select words and phrases. Much more, too, than a rebus, or a coded message in symbols, or a cut-and-paste bank robbery note aiming to obscure the identity of the sender. There are strong hints of meaning winding and weaving around the text. Or at least I believe there are, because as the song goes on, these words act upon me and engender a strong emotional response.

Night wings, her hair chains. Here’s your wooden greenback: sing. Wooden beams and dovetail sweep—I struck that picture ninety times. I walked that path a hundred ninety long, low, time ago, people talked to me.

What exactly I am feeling is hard to pin down. It’s a powerful mix of unease, longing, bitterness, and resignation. If this really were nothing more than a diversion, a string of words artfully arranged only to signal some deeper meaning that the poet never actually bothered to work out—would I feel the connection I do to this song?

A pistol-hot cup of rhyme. The whiskey is water, the water is wine. Marching feet: Johnny Reb, what’s the price of heroes? Six in one, half dozen the other. Tell that to the captain’s mother.

Thus far I’ve gone on and on about Michael Stipe, when I had promised I’d be talking about R.E.M. Let’s be clear: poems are poems, but songs are songs. And the difference between a poem and a song is an added dimension (maybe two), a shift of gears, an all-in raise thrown into the pot. The lines from “Swan Swan H” (Apple Music, Spotify) that I’m transcribing here are neutered on the page. You don’t read them as the artist sings them, and what’s still worse: they’re entirely removed from the song—from the minor key treatment that beautifully complements Oblique Stipe Lyrics here, as in so many R.E.M. songs;3 and from the acoustic guitar/ mandolin/ snare drum arrangement that gives the song its bygone and timeless flavor. Buck, Mills, and Berry are essential to everything this band does.

So now we have established that getting your head around R.E.M. means cutting loose from the comfort of certainty and absolutes. It means embracing a poetics that greatly favor obliquity and evocation over black-letter meaning and telling it straight. Sometimes you can reverse-engineer a setting, a theme or even a position, especially from the more overtly political songs. For example, “Welcome to the Occupation” (Apple Music, Spotify) speaks to U.S. Cold War policy in Latin America, and “Bad Day” (Apple Music, Spotify) means to survey the damage done by 9/11 to the American psyche. But even in these cases, the take-home messages aren’t delivered verbatim into your waking mind. You tend instead to find them lodged in your gut, after a handful of listens. It’s all subtlety and sleight of hand, and either that works for you or it doesn’t, depending on your clockwork.

But R.E.M. being R.E.M., once you’ve acclimated yourself to their songs acting upon you in this way, they’ll go ahead and pull the rug right out from under you. They’ll do the unthinkable and drop a song like “Everybody Hurts” (Apple Music, Spotify).

When your day is night alone, if you feel like letting go, if you think you’ve had too much of this life … well, hang on. ’Cause everybody hurts. Take comfort in your friends. Everybody hurts … so hold on.

A simple and essential message, stated beautifully. And by R.E.M.?!? In its 1992 review of Automatic for the People, Rolling Stone gave the band considerable props for this song’s “startling emotional directness.” A quarter century later, The Quietus felt compelled to address claims that on Automatic the band climbed down from “the magic and strangeness” of its earlier records—i.e., it had sold out. The reviewer argues that it was really just “Everybody Hurts” that departed from classic R.E.M. esoterica on this record, and for that matter, as uncharacteristically “direct” and “explicit” as that song was, “it would be churlish to deny its power.” I’d go the further step of arguing that “Everybody Hurts” derives at least half that power from the fact that of all people, it’s Michael Stipe singing it.

But let’s not pretend, either, that this was the first time Stipe stepped out from behind his siegeworks and walked among us, bare-chested and showing his scars. I would submit that “You Are the Everything,” released one album earlier, was Stipe’s trial balloon for “Everybody Hurts.” Maybe not all his cards are thrown down on the table here. But come on: Sometimes I feel like I can’t even sing. I’m very scared for this world—I’m very scared for me … ? That’s pretty goddam front-and-center.

Here’s a scene: you’re in the backseat, laying down. The windows wrap around to the sound of the travel and the engines. All you hear is time stand still in travel. You feel such peace and absolute, the stillness still that doesn’t end but slowly drifts into sleep.

R.E.M. songs are thick with scene-setting, but this one stands apart for its universality. We may never have stood behind a firehouse listening to a soapbox evangelist, but we have all been this child, half-awake, carried down the road in a car at night, dropping our guard and surrendering to the Trusted Driver. And I expect all of us hunger from time to time, as Michael does here, for that feeling of security we had, when someone was taking care of us.

The stars are the greatest thing you’ve ever seen, and they’re there for you: for you alone, you are the everything.

Preach, Michael.

Yes: I count Michael’s larynx as an instrument. And a magnificent one at that.

There was a boy named Bob Luscombe in my German class in high school. He was an alt-rock kid with red hair buzzed around the sides and back, long, curly and floppy on top. He wore a fatigue jacket and spoke hardly at all, except occasionally with the girl in front of him and when called upon by Frau Hrabowy. He sat catty-corner from me and would drop his army-surplus backpack on the floor of the aisle between our desks. On the canvas he had carefully painted these words:

I found it. Miles Standish proud.

Flora Amanita: Indigenous to Meso-Amer. flora

= A dying river. This is where we walked. Swam. Hunted. Danced. Sang.

What noisy cats are we.

Back then I had no clue what any of this meant. Two years later I bought R.E.M.’s fourth record, Life’s Rich Pageant, and I recognized these phrases, among others, inscribed in the liner’s notes. Actual song lyrics, in some cases, and in others, annotations to help listeners dig just a bit deeper into Michael Stipe’s mysteries.

About a year ago I went online to see what had become of Bob Luscombe, and I saw that he had died in 2006—of natural causes, I read, at 36 years of age. This hit me harder than I would have expected, given how little I knew him. As I sit here writing today about poetics and clockwork and the buttons and switches we all may or may not have in our emotional programming, I think I finally understand why.

For other examples, try “Oddfellows Local 151” (Apple Music, Spotify), “I Remember California” (Apple Music, Spotify) and of course “Losing My Religion” (Apple Music, Spotify).

It wasn’t until I had a kid that You Are the Everything really hit me. Once I realized I was the driver and he was the kid in the song, I can’t hear that song without getting emotional. So good.