Siouxsie & the Banshees, "Helter Skelter"

If you weren’t able to catch Pistol, Danny Boyle’s six-episode miniseries about the rise and fall of the Sex Pistols, I don’t know what to tell you. It streamed on Hulu and Disney+ starting in May of last year. Now it’s been wiped from both platforms, for “tax reasons” (whatever that means), and there’s no known plan or promise for when it’ll be reposted.

Now it’s not like the Sex Pistols story was never told before. There are at least three feature-length films on the subject, including The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (1980), Sid & Nancy (1986), and The Filth and the Fury (2000). On the bookshelf across the room here I have copies of John Lydon’s memoir, Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (1994), and John Savage’s England’s Dreaming (1991), probably the definitive retelling of the late ’70s UK punk scene writ large, with special attention given to the Pistols throughout. If you’re curious about the Sex Pistols, any or all of these resources are available to get you up to speed.

Knowing this story inside and out, I still found Pistol a pleasure to watch. The series is based on guitarist Steve Jones’s autobiography, Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol (2016), so that known elements of the story are told from an altogether new perspective, with loads of new and interesting data points sprinkled over top. In the opening scene, for example, Jones and future Pistols drummer Paul Cook break into a London concert venue to steal David Bowie’s touring equipment for their DIY band. This was news to me, and the story only got better over the remaining 5.9 episodes.

There’s a ton about this series that I loved, and that would cause me to recommend Pistols fans and punk-haters alike to watch it, if you could find it anywhere. Per the conventional wisdom—which this show affirms—band manager Malcolm McLaren and front man Johnny Rotten were a combustible mix with incompatible visions. Played by Thomas Brodie-Sangster (previously Ferb, Jojen Reed, and the adorable kid from Love Actually) and Anson Boon, these two are mesmerizing to watch. Brodie-Sangster’s McLaren brings limitless charm to his self-declared project of destroying … everything, and Boon’s Johnny Rotten is magnetically awkward, stooping, and earnest about exempting at least the band from the destruction. The McLaren-Rotten conflict takes center stage in the later episodes of the series, as well it should. Had Shakespeare been on the King’s Road in 1977, he couldn’t have improved upon these tragic characters.

I used to identify with Johnny. Before his act wore thin, he was the poster boy for punk cynicism. My sense of cynicism is that, properly construed, it’s nothing more than idealism interrupted. You imagine what the world could be, you see it as it really is, things start to break—your heart, your brain, your spleen—and ugly stuff comes out of the cracks. There are many reasons why the Sex Pistols are still remembered, but Johnny’s spitting, snarling cynicism is the sole reason why anyone, including me, actually listens to their records in 2023. By contrast, McLaren basked in all that was wrong with the world. If anything, he was determined to leave everything he touched worse than he found it. Cynicism, meet nihilism.

Johnny and Malcolm aside—or better yet, sent to their opposite corners—the best thing about Pistol is Chrissie Hynde. I’ve written about Our Ohio Girl before (see “My City Was Gone”), and I even mentioned that she ran with the UK punk crowd before she formed the Pretenders. As it turns out, Chrissie was a close friend/ onetime love interest of Steve Jones, and she naturally gets a good deal of attention in a series told from Jones’s perspective. Other future stars—Billy Idol, for one—flash briefly on-screen, almost as Easter eggs for rock geeks like me. But Chrissie plays an essential role in Pistol’s narrative ebb and flow: she’s the All-Purpose Angel riding the right shoulder of Punk London. While McLaren flogs his fake ideology and eggs the band on to offend the sensibilities of All Britain for profit, Chrissie stands fast for the proposition that the music is the essential expression. And when her soul-sucking American counterpart Nancy Spungen lands in town looking to bag herself a punk rocker, here’s Chrissie Hynde trying her best to pull Sid Vicious out of harm’s way.

To be sure, for most of Pistol’s six episodes, Chrissie fails on all fronts. She sets her pal Steve on a constructive course, only to watch McLaren divert him over a cliff. And of course we all know how it ends with Sid and Nancy. Chrissie sees better than anyone that the Sex Pistols—her friends—are moving too fast and slipping off the rails, but she can do nothing to stop the train. And for herself, bands in the punk scene keep inviting her to join, only to drum her out days later—the men are put off, we’re told, by her obvious talent as a songwriter.

But there’s a payoff at the end. For sure, the Pistols crash and burn. Or rather, burn and crash. And maybe that brings us to the best metaphor for this band: they were just a big, dumb rock hurtling through the atmosphere, catching fire, and plummeting to Earth. “Meteoric rise” is a phrase we use a lot, despite the fact that the singular quality that defines a meteor is its downward trajectory. The Sex Pistols gave us the Full Meteor Treatment, rising and falling in an almost perfect parabolic arc. The crater they made on impact would turn out to be the Ngorongoro of rock music: timely, massive, and fertile as hell. And one of the first flowers to grow out of their ashes was the Pretenders. In its last episode, Pistol does us the courtesy of showing—well, nearly showing—Chrissie finally finding her stride. She takes punk’s best ingredients, integrates them into her songwriting, leaves the drama behind, and off she goes into the big, wide world. Great story.

There’s another great story that could be told here, about another woman who ran in these same circles. She took a very different aesthetic direction from Chrissie’s, but she was every bit as daring, brilliant, and important, and I will fight anyone who says otherwise. Of course I’m talking about Siouxsie Sioux.

Siouxsie was more than just a bit player in the story of the Sex Pistols. Along with the aforementioned Billy Idol, she was a part of the “Bromley Contingent,” a gang of committed fans from the London suburbs. See “Any Wednesday.” In fact, when Thames Television needed to gather a representative sample of local punks to flavor up the Pistols’ appearance on its December 1, 1976 broadcast of Today, Siouxsie was on hand to join. It was Siouxsie that leering middle-aged host Bill Grundy propositioned during the interview, prompting Steve Jones to curse him out on live TV: You dirty bastard … you dirty fucker … what a fucking rotter.

This, more than anything, put the Sex Pistols into the public eye, like a red-hot poker. And depending on your perspective, it was all uphill or downhill from there.

Siouxsie might have been a footnote of history, but by this time she’d already formed her own band with Steve Severin (also at the Grundy interview: back row, second from left) and Marco Pirroni, who would later go to play guitar for Adam and the Ants. In fact, Sid Vicious was Siouxsie’s first drummer, before he joined the Pistols on bass.1 Siouxsie and the Banshees had played their first gig at the 100 Club Punk Festival in September 1976, as one of the Sex Pistols’ opening acts. The setlist consisted of a single 20-minute improvisation called—and reciting and riffing on—“The Lord’s Prayer.” After the Grundy incident, Siouxsie and Steve prudently scaled back their personas as Pistols superfans and turned their attention instead toward developing their band’s sound—i.e., inventing post-punk. Within two months Siouxsie and the Banshees were touring England on their own.

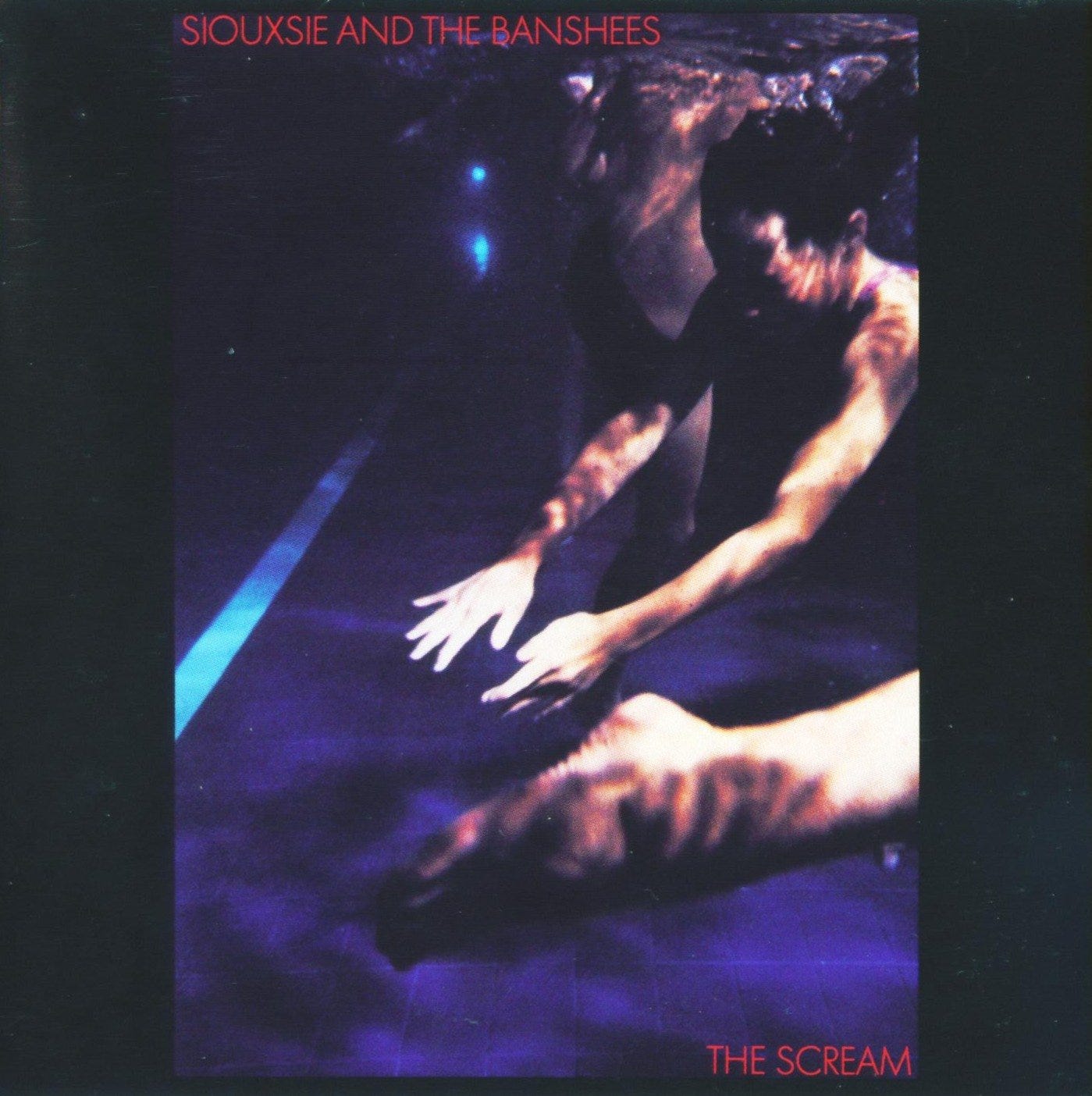

By 1978 the Banshees were well clear of punk rock. They had a distinctive sound: piercing, frenetic, and intense—perfectly complimented by Siouxsie’s howling/ yelping vocals. After a fan went on a graffiti spree, marking up various labels’ HQs— SIGN THE BANSHEES DO IT NOW—Polydor bought in. The Scream issued in November, a full year before the first Pretenders record would hit shelves. Songs like “Mirage” (Apple Music, Spotify), “The Staircase (Mystery)” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Overground” (“Apple Music, Spotify”) are strong examples of what the early Banshees were going for: start with punk’s sharp corners, hone them to a razor’s edge, kick all R&B and rockabilly influences to the curb, and fill the gap with occult mysticism and psychedelia. Wait: so did they invent both Goth rock and post-punk? Hard to say for certain, but “Metal Postcard (Mittageisen)” (Apple Music, Spotify) is Bauhaus before Bauhaus, if only by a nose.

I’m arriving later to Siouxsie than I should have. I remember the “Peek-a-Boo” (Apple Music, Spotify) video on MTV. (See “Lazarus,” on 120 Minutes.) I bought the “Kiss Them for Me” release on CD single in the early 1990s. The B-sides for that single, “Staring Back” (Apple Music, Spotify) and “Return” (Apple Music, Spotify), were gorgeous, and about five or six evolutionary steps from The Scream a dozen years earlier. When I was traveling in England, I bought a couple two-CD compilations, The Best Punk Album in the World … Ever!, vols. 1 and 2. These featured “Christine” (Apple Music, Spotify) and “Hong Kong Garden” (Apple Music, Spotify). I heard “Cities in Dust” (Apple Music, Spotify) on a mixtape some other guy (!) had made for Kate. There was enough here for me to shell out for the two singles compilations, but I left it there for the next two decades.

Since Kate bought me the turntable two years ago, I’ve had to beat back the impulse to buy albums on vinyl that I already have on CD. I don’t always win that fight, and so I have, for example, My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, OMD’s Architecture & Morality, and R.E.M.’s Life’s Rich Pageant in my collection. But lately I’ve been able to tap into some pretty rich veins of terrific music I hadn’t previously explored, and that’s the sweet spot for buying records. Krautrock, for sure: I’ve bought a ton of Krautrock on vinyl. But also Siouxsie: I have the hits on CD, but none of the studio LPs, which are uniformly celebrated by critics I trust. Last summer I found a vintage copy of The Scream in a record store in Amsterdam. Four months later I fished a Ju Ju reissue out of a store in Soho—barely a block away, as it turned out, from where Siouxsie would have held court at the Batcave club, back in the 1980s.

These two records have me, well, spellbound (Apple Music, Spotify).

We’re deep enough into this post now where it’s about time I picked a song. This is a hard choice to make, and it helps only a little that I’ve name-checked so many nominees, with accompanying links, in earlier paragraphs. After minutes of tortured deliberation and appeals for divine direction (and of course He recommended “The Lord’s Prayer” (Apple Music, Spotify)), I’m going with “Helter Skelter” (Apple Music, Spotify) from The Scream.

“This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles,” Bono says, introducing their version of the song (Apple Music, Spotify) to a live audience on U2’s Rattle & Hum record. “We’re stealing it back.”

On that score, I like to imagine Bono et al. peeling out of the Spahn Ranch in an unmarked van sometime after midnight in November 1987. This would have been a side excursion during The Joshua Tree Tour. The Edge is driving and has the hammer down. Adam Clayton pulls a balaclava off his face. He and Larry did the legwork and are catching their breath in the back of the van.

“Did you get it?” Bono asks. Adam hands him a black duffel bag. “It’s in there,” he says. Bono nods, unzips the duffel, pulls out a wooden box, picks the lock on it with a hairpin. He flips the lid open on its hinge. “That’s it, yeah?” The Edge is asking. After a long pause, the guitarist asks again: “The song? We have it?”

“No,” Bono says. “We don’t.” He shakes his head. “There’s just this sheet of paper.” Which he reads aloud:

13 November 1978

CHUCK, YOU NAUGHTY BOY: THIS WAS NEVER YOURS.

XOXO —SIOUXSIE SIOUX

Last summer I put The Scream on the platter, dropped the needle on Side A, and just listened. I hadn’t looked at the track list and didn’t know what was coming. About 14 minutes in, a song ended with hand claps and feedback, then a grunt. After that, there came a slow—very slow—drip drip dip of bass notes, fully six seconds apart, and following three or four of these, erratic, off-beat guitar scratches and squeals joined the mix. I wondered where this was heading. Then came Siouxsie’s vocals, overlaid with drum strokes:

When—I—get—to-the-bottom—I-go-back—to-the-top-of-the-slide …

OMFG.

And the drums and guitar and bass accelerated, faster and faster and faster, swirling into a maelstrom of Beatles-wrecking perfection, culminating two minutes later in The Single Most Necessary F-Bomb Paul Could Never Have Gotten Away With in 1968:

Tell me, tell me, tell me—TELL ME THE ANS-WERRRRRR …/ Well, you may be a lover but you AIN’T NO FUCKING DANCER.

Then the chorus, then one more half-turn around the merry-go-round:

When I get to the bottom I go back to the top of the slide, and I stop—

End Side A. This was one of the best things I’d ever heard. 100 listens later, it still packs the same punch, if not the same surprise. I play this song and I want to run up the street overturning cars. Siouxsie and the Banshees are just that goddam good.

By the way, where’s Bill Grundy now (Apple Music, Spotify)?

According to Rotten’s memoir, original bassist Glenn Matlock—wearing the red pants in the Grundy interview—left the group after his three bandmates ejaculated into an omelet and fed it to him. This would arguably qualify as “constructive discharge” under the law. (Attorney joke.)