Last Sunday I was riding into Watertown with my sixteen-year-old, to pick up buffalo wings. This is the first thing we do when my wife and daughter leave town. Driving up Galen Street, Florian asked what I thought of Billy Idol. I explained—unnecessarily, because this was not Florian’s question—that before he formed Generation X, Billy Idol was part of “the Bromley Contingent,” a group of kids from a London suburb who tagged along with the Sex Pistols. Loved the band, dug the scene, followed them to all their shows and went nuts in the crowd.

At this point my mind took me somewhere else, and I trailed off. After a pause, I swallowed hard, and with tears in my eyes I added these six words:

“Like I was, with the Februarys.”

(NOTE: This is the beginning and end of what I have in common with Billy Idol.)

My mind went down this road because on March 10 Brent Young died of cancer. Brent was my sister’s best friend. I suppose he was a friend of mine, too, but I can’t claim to have been especially close to him. It’s more of the truth to say I was close with people who were close with him. From this distance I knew Brent as an artist, a smart ass, a big brother, and a bit of a goof—always with a twinkle in his eye and a huge smile ready to break across his face, if it hadn’t already. That short list of what I knew and remember of course doesn’t capture the whole of who he was or what he meant to the people who loved him so dearly.

So let’s keep after it. Let’s add into the mix that he was an absolute guitar hero, and that he and Scott Hevener and Joe Berquist and Chris Mendt and Alan Brooks wrote two dozen songs that, more than anything else, were the soundtrack for the college years of a hell of a lot of people in the Mahoning Valley in the 1990s. That gets us a bit closer, and closer still if we start thinking about the Februarys in terms of community.

Lately I have been thinking a lot about community—what it means, how hard it is to build, and how much we need it—because here and now I am feeling most acutely the absence of it. Some of this has to do with living here in the Northeast with very reserved people. Go to a rock show at the Orpheum, and witness the extreme reluctance of the gathered crowd to get up out of the seats, much less dance. My next-door neighbor pulls his car into the garage and closes the door behind him—while still in the car—in order to avoid having to say hello to anyone who might be passing in the street. Belmont High School closes and locks its doors at 3:15 PM for security reasons; just you try and find your way into the building to watch your kid’s swim meet. COVID-19 only exacerbated this trend away from community, spinning us off into isolation with our families (thank God for mine) and our smartphones. By the time we stepped out into the sunshine again, we’d forgotten how to be together and why it was important.

Brent Young and the Februarys were at the core of a real and important community in the early 1990s. They were a center of gravity that gathered in, and kept gathering in, so many of us who had been hurtling around the Valley in unsettled trajectories, seeking out not just steady connections so much as a sense of belonging. When I say “so many of us,” I mean kids coming of age in that moment who felt out of step with, and maybe a little alienated by, the codes and customs that determined belonging in a high school setting. With Brent, Joe, Scott, Chris and Alan, all you needed to belong was to love the music—and the music was easy to love.

When the February played gigs, more often than not they were appearing at Cedars Lounge in Youngstown. Cedars was on Hazel Street, just off Commerce Street downtown. To get to Cedars from Howland, you took Route 11 South ten miles, drove past the strip malls and fast-food joints on Belmont Avenue, turned left at the cemetery, then right on Fifth Avenue. Proceeding down Fifth Avenue toward the city center, you took note of the decrepit state of the mansions where the Valley’s wealthiest residents used to live, and when you passed Wick Park you double-checked to make sure your doors were locked. You would continue on Fifth Avenue, past the University and the ominously-titled “Minimum Security Correctional Facility,” and when you reached the End of Civilization, you’d hang a left, park your car, and hustle into the bar.

I don’t know if Cedars was any kind of anything before the Februarys and related bands—Figure Ground, Boogie Man Smash, As Big as Love—came on the scene. But I’m gonna say it wasn’t, because it suits my thesis. Downtown Youngstown on a Saturday night was empty. Desolate. Notable graffiti on the wall of the men’s room at Cedars read YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO: BIG CITY CRIME WITHOUT BIG CITY CULTURE. If you didn’t grow up in the Valley, and you’re wondering what this could mean, check out this podcast (Apple Podcasts, Spotify). You’ll hear about how two generations ago the Mahoning Valley was a center of industry, and how the steel mills and auto plants spun off a honeypot of wealth and prosperity that attracted the Cleveland and Pittsburgh organized crime families to the area. Decades of gang wars and killings followed, and the mob stuck it out in Youngstown even after the steel mill closures in the late 1970s plunged the area into permanent economic decline. But putting aside one ambiguous incident that, depending on your perspective, was either a very polite mugging or a simple exchange of cash for services—after all, the gentleman providing the unasked-for protective escort to our cars never pointed his gun at us—we never worried about crime outside Cedars. By the early ’90s, even the criminals didn’t want to be downtown.

But we did. We ditched our enclaves in the suburbs, and we packed into Cedars because the bands were playing, and—which was still more important—because other kids like us were going to see the bands, too. From the East Side of Warren, from Cortland, from Boardman and Canfield and Austintown and Lowellville and anywhere else in Trumbull and Mahoning Counties, we all made the trip to Cedars Lounge. To call it a “lounge” was a real stretch: this was no Copacabana. There were at most ten, fifteen seats at the bar, which as far as we knew stocked one kind of beer (Rolling Rock, in the bottle) and made one mixed drink (the celebrated “Vulcan Mind Probe”). The low ceiling trapped the cigarette smoke, the better to ensure that it fully saturated every last fractalized bit of your lungs. But there, in that dingy bar in the deserted city, itself a monument to the death of heavy industry in the Midwest, we found and formed a community.

And Brent Young was as instrumental in that community’s formation as anyone.

In my gang at Howland, we used to imagine ourselves in bands quite a lot. We shot Camcorder videos in our basements miming to R.E.M. and Cure songs. Bob and I used to kick around band names, album concepts—we even came up with song titles: “(Just Let Me Put My Socks On And) I’ll Walk My Own Ass Home” would be a fun country goof, if we ever sat down to write it. I kept in my backpack a handwritten list of songs I felt competent enough to play on the drums, in case anyone should ask. But we were just fantasizing. The Februarys actually got on their horse and did it. Or we assume they did. We never saw them rehearse, and we had no insight into how it all came together. They would take the stage at Cedars, fully realized, with their own songs, and they played them masterfully. It all seemed so effortless.

I ended up going to college out of state. Couldn’t make the shows except during holiday and summer breaks. The Februarys got into the habit of playing on Christmas night, which was always a treat. Friends would show up at my grandmother’s house, where my family was gathered, until the numbers reached a critical mass and we loaded up for Youngstown. Brent would wear a Santa hat. (Tia reminds me that he would come to our house in Howland every year to help put up our Christmas tree: “Dad paid him in eggnog.”) When I was at school I’d stay caught up with the band through my sister and my gang in Columbus and Warren. They’d brief me on the Febs’ plans to go into the studio, they’d send me a recording of a recording from the sound desk at the Kent State Battle of the Bands, or they’d report that a skinhead had jumped on stage at the Penguin Pub and taken a swing at either Brent or Joe (I forget who).

In 1994 I thought I had booked a gig for the Februarys to play the P-Party event at Princeton. (I had joined the Undergraduate Student Government’s Social Committee for the sole purpose of lobbying the USG to bring better bands to campus.) They would have opened for Live. The Febs were all geared up to come, but the booking fell through and I was hugely embarrassed.

The last time I saw Brent in person was at Sam Gorant’s bachelor party in Boston. Brent, Joe, Mark, and I ate dinner together in the North End. Over a plate of calamari Brent gave me some shit for liking Camper Van Beethoven. Glint in his eye, cackling, the whole production. I remember this because at 34 years of age I still cared what he thought, especially on all matters musical. Tia gave me his number, and I texted him the week before he died. At one point, while he was in the hospital, Tia was FaceTiming with him. Out of nowhere she told him: “You know Brad Abruzzi still worships you,” and he smiled. There was a time where I would have kicked her for saying that out loud. But not now, because she had it right on.

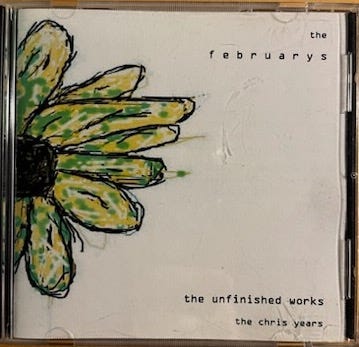

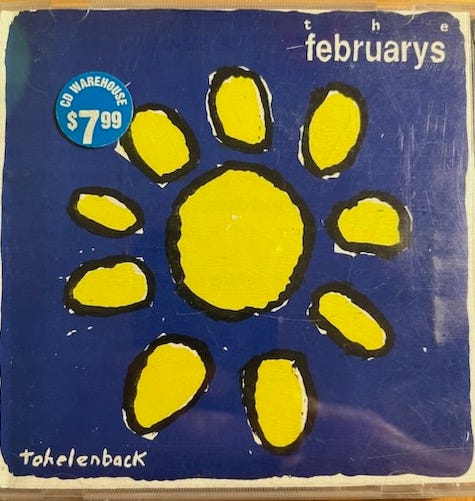

The song I picked for today is “Any Wednesday.” The Februarys recorded two studio versions of it—the original came out on a cassette single, with “She Doesn’t Walk” on the B-side, and the re-recording appeared on their tohelenback LP. They’re both terrific, and I can’t tell you which one was better. No links today, unfortunately, because Febs tracks aren’t posted to the streaming services. At some point I’m gonna talk to Joe about fixing that. But I did find this live performance of “Any Wednesday” on YouTube:

There are deeper cuts I could have chosen here—a lot of songs that are just as good and maybe better (?) than “Any Wednesday.” Let’s throw some titles out on the table. Original Februarys compositions: “Telephone Message,” “And Jenifer’s Tigers,” “Does Your Father Know,” “Pay Her a Dollar,” “Wonder When,” “A Dozen Roses,” “Andie with a Zippo,” “Spin.” And the covers, too: “I Want Candy,” Icicle Works’ “Understanding Jane,” “Angels” by the Bodeans, the Afghan Whigs’ “Rebirth of the Cool.”

But I picked “Any Wednesday,” because it was the song the Febs always played last at their shows, and I want to go back to Cedars, ca. 1992, one more time.

It’s ten to two in the morning. My gang is a sweaty mess. We’ve been bopping around in the pit for a solid eighty minutes. We’re all stripped down to T-shirts. There’s beer in my hair, my legs are cramping, and my airways all but closed up (asthma), and all I’m thinking is I don’t want this to end. Tia is up ahead of me in the front row with her crew, in her VIP slot away from the mosh. Standing just over her, on the left side of the stage, is Brent. His head is dropped down, looking over his several effects pedals. He plays the guitar with care and confidence. He is not overly animated, but now and again he’ll look up and make eye contact with Joe, who is out on the right side, with Scott standing in between them. Joe rambles around the stage a bit more, and when he sees Brent, they both smile, as if they’re asking each other: Can you believe we’re doing this?

The band finishes “I Want Candy.” Tommy flips a switch behind the bar, and the lights come on. Scott banters with us a little. There is time for one more song, which is just about right, because this crowd is wiped and we have only one more burst of energy to give back. Mark and Jimmy start yelling for “Green Like Me,” like they always do. We’re half-laughing and half-annoyed, because the answer here has always been, is now, and forever shall be “Any Wednesday.”

Alan does a four-count with his sticks. In comes Our Guitar Hero to play the opening. And the Februarys lift us off the ground—together— one last time.

* * *

Nothing here is going to put words to what Brent meant to my sister, or to Joe or Scott or anyone else who was so much closer to him than folks like me in the Howland Contingent. But to us he still meant a whole hell of a lot. We love and miss you, Brother.

So wonderfully told! I wish I had known Brent.

Awesome homage to Brent. I too was a member of the sweaty youth at cedars but also had the privilege of living with Brent for a number of years and working on a number of band projects with him. I feel honored to have been able to spend time with him and speak with him briefly before he passed. I’ve watched that video a number of times recently and loved “Any Wednesday” encores. (BTW @ 6:17 into the video I might know the guy behind Brent 😏”