The Violent Femmes, "Add It Up"

On April 23, 1993, I got to spend an afternoon with the Violent Femmes.

Back in our freshman year, my very good friend Glenn1 had joined the USG Social Committee. USG was our Undergraduate Student Government, which I tended to associate with irksome petitioners banging on my dorm room door all day during “election season,” asking me to sign some document or other so they could get on a ballot. It was a kind of hostage taking. You’d answer their knocks, and they’d start in with these interminable canned recitations on matters of University administration you weren’t previously aware of and couldn’t care less about once you were.

Yeah yeah yeah just give me the pen. Whatever. I’m in the middle of a Tecmo Bowl game.

USG was for tools.

When we landed back on campus as rising sophomores, Glenn urged me to join him on the Social Committee. This was low-level committee work, and you didn’t need to run for office to get involved. I.e., no door-to-door petitioning. Still, I thought. These government kids: TOOLS. But then Glenn explained that it was the Social Committee that chose the bands USG invited to campus. Turns out I did have an interest in at least some of this government work.

The Social Committee had a yearly budget to spend down on hired-in entertainment. And if I remember correctly, we had a list of available acts. Sort of like a catalogue. For the most part we brought in music groups, but on occasion we’d invite a comedian. In December 1993 Adam Sandler came down from New York to perform in Dillon Gym, where most of these events were held.2 I don’t remember if Glenn and I played any kind of role in this decision, but I can say we were true believers at the time. We had a dubbed-to-cassette copy of Sandler’s comedy record They’re All Going To Laugh at You floating around the dorms, and we played the hell out of it. We had most of the sketches committed to memory and were constantly reciting lines from them. “Tollbooth Willy” (YouTube), “The Buffoon and the Dean of Admissions” (YouTube), and so on.

There are two things I remember about the Adam Sandler show, neither of which have anything to do with him performing. First, I remember Adam killing time on the gym floor in the hours before the performance, while USG members and select friends looked on. Someone had found him a basketball, and he was strutting around the court, dribbling and shooting, while girls (women?) from my class positioned themselves at half-court with their hips swung out, trying to make claims on his attention. Self-evidently a mating ritual, from which all of us men (boys?) were self-evidently excluded. Barf.

Second, Adam brought Norm MacDonald with him to open. Norm had just joined Saturday Night Live as a writer, and we didn’t know who he was. The Social Committee hadn’t negotiated for this and didn’t know he was coming. Sandler just brought him along. And Norm killed. He was unbelievably funny. He did a bit about a woman with multiple personalities—Can I talk to the whore?—that had us floored. Turns out that bit morphed into this Season 20 sketch a year later. Honestly, it played much better in Dillon Gym.

Bands we brought to campus while I was on the Social Committee included Live, the Spin Doctors, the Connells, the Samples, Toad the Wet Sprocket, and Rusted Root. As I look back over that list, I don’t see that I was a very influential member of this Committee at all.

In my (and the Committee’s) defense, the range of options was limited. There was a very narrow sliver of the market available for us to consider. Bands had to be (1) within reach of our budget, and (2) not too big or too proud to play in a college gym. They probably had to be (3) American, too, now that I think of it. Canadian might have worked, but the British bands I so adored then and now weren’t going to be on hand. If they were in the U.S. they were already touring, jumping city to city on tight itineraries with no room to add stops at private colleges.

Looking back on these days now, with a much better understanding of how life, markets, the music industry—hell, even immigration law—work, I get it. Live, the Spin Doctors, the Connells, the Samples, Toad, and Rusted Root were exactly the sort of bands to pull for P-Party in Dillon Gym. Standard-bearers for the ’90s, footnotes to history, not the worst acts in the world but certainly not the best, either. If you wanted to see the Sundays, Morrissey, Oasis, the Ramones—you needed to take the train to Manhattan. If you wanted U2, REM, or the Cure, you were bound for the Meadowlands or Nassau Coliseum.

Still, we did bring in the Violent Femmes. And I don’t know how we got to that result. For sure the Femmes checked all three boxes, in terms of availability, price, and band interest. What I can’t remember is how or why our colleagues on the Committee got their heads around choosing them over, say, the Posies or Gin Blossoms. It’s possible I rose and gave a stirring and forceful Henry-Fonda-in-Twelve-Angry-Men disquisition that swung the rump of the Committee behind the proposition of inviting the World’s Finest Acoustic Pop-Punk Power Trio to Princeton. That’s good theater, and I’ll certainly keep it in mind for the screenplay adaptation of this Substack. But it doesn’t sound like 19-year-old me. Maybe I lobbied Glenn, and he spoke in favor of them? However it happened, the Committee did reach this uncharacteristically insightful answer, and for that I’m prepared to claim at least a modicum of credit.

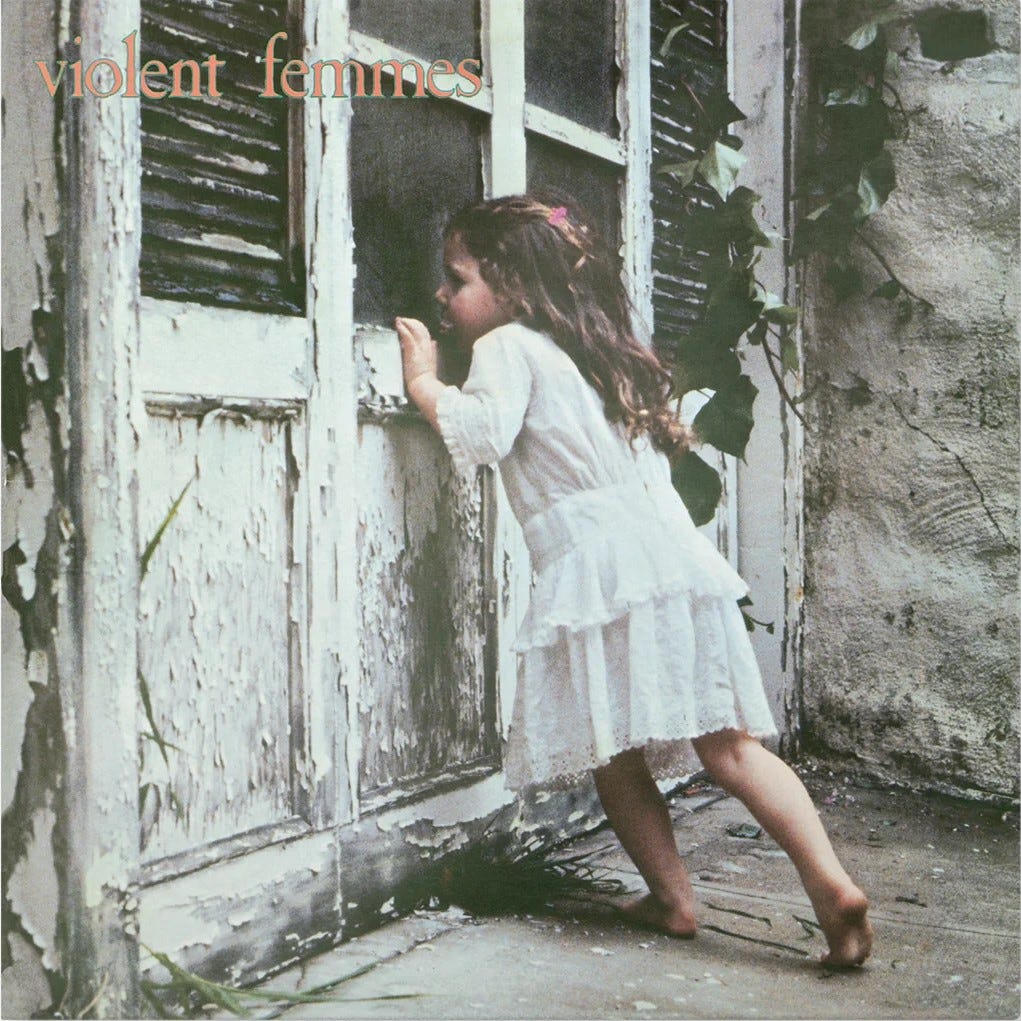

For so many of us who came of age in Ohio in the mid- to late 1980s, the Violent Femmes were old friends. I should be more specific: The Violent Femmes, their self-titled debut album, was the old friend. We didn’t know the first thing about the band itself. Turns out they did appear in a video, for “Gone Daddy Gone” (YouTube), but it never earned significant airplay on MTV, and I don’t think I saw it until I was in college. That album, though: whew. Like denim jackets, lip gloss, and AC/DC graffiti on desks, the ten tracks on The Violent Femmes were silk threads in the rich tapestry of Rust Belt teen culture, ca. 1983 to 1991. This notwithstanding that if the Femmes walked into our school and down the hall, not a single one of us would have pegged those three guys for delivering unto us a most treasured artifact of our age.

I was nine years old when The Violent Femmes came out in April 1983. Up to and through my high school graduation, that self-titled LP was everywhere but on the radio, and in all that time I don’t think I ever saw a store-bought copy of it. Seemed like everyone we knew had a copy of a copy of a copy on a Maxell, Memorex, or TDK cassette. Some of those hand-me-down tapes were so old they were BASFs. The songs on The Violent Femmes were passed down to you from your older brother or sister. If you didn’t have an older sibling, you got them from your friend who got them from his brother or sister. And passed down, along, and around with these songs and the battered tapes that played them was an authoritative and complete read of adolescence: the power and the glory, and the abject misery, of growing up.

Side A: “Blister in the Sun” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Kiss Off” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Please Do Not Go” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Add It Up” (Apple Music, Spotify), and Confessions (Apple Music, Spotify). This is probably the bangin’-est, most satisfying, all-highs/ no-lows side of a record ever produced. And were it not for Side A, Side B might have a claim on all those superlatives.

The sound was unique. It still is, really, because no one would dare to imitate it. Guitars, acoustic bass, brushes on drums—from time to time a xylophone—with Gordon Gano’s nasal vocals slashing across it all like a scythe. Most all of the songs are played fast, with rhythm guitar, too. Unplugged punk with a splash of Americana and the occasional excursion into reggae or swing. The messaging was spot-on, too: if you were lonely, desperate, alienated, defiant, vengeful, pleading, snarky, profane, and not especially concerned about your permanent record, then Gano’s lyrics had a red telephone direct-line connection with your soul.

I think I got my copy from my sister. Or some friend or acquaintance left the cassette tape in my car. A dubbed cassette with The Violent Femmes on it generally wasn’t labeled, because the person who made it couldn’t be troubled with this sort of detail. Or if they had, that label peeled off and into the guts of somebody’s car radio years before the tape ever landed in your hands. This was real samizdat hand-to-hand business, some of which probably had to do with the “adult content” of the songs. Tame, by today’s standards, but for many of us “Add It Up” was the first song we would ever hear with an F-bomb in it.

Nowadays fucks are sprinkled into song lyrics like salt and pepper. Shaken out of the fuck dispenser, they land here, there, and everywhere. In 1983 you had to build up to your fucks. You had to ask, first, Why can’t I get just one kiss? And you had to let that rhetorical question simmer for eight bars before proceeding to a second, intermediate question—Why can’t I get just one screw? That was another eight bars, and after that an eight-bar bass solo was in order, while you went looking for a glass of water or something stiffer to steel your nerves, so you could put it all down on the line, as Gordon did:

Why can’t I get just one fuck? Why can’t I get just one fuck? I guess it’s got something to do with luck, but I’ve waited all my life for JUST ONE—

And off you went from there into the chorus, which while expletive-free was still super-satisfying for all us kids to shout-sing in our bedrooms when we were home alone, or rumbling down Howland-Wilson Road in the car with all our friends. DAAAAAAY AFTER DAAAAAAY, I GET ANGRY, AND I WILL SAY … And not just “Add It Up,” but all the other tracks, too, loud as you could sing them. You can all just KISS OFF INTO THE AIR. That bitch took my money and she went to Chicago, if I’m not already enough SICK AND ALONE. I’M GONNA HACK-ACK-ACK IT APART. And so on.

For sure the Smiths had their place in teenage life—there was no better choice for your tape deck, if you were in a wallowing sort of mood. But if you wanted to hit rock bottom out and rebound up the ladder, then Gordon Gano was your vibe. Make no mistake, Gen Z: we suffered microaggressions, too, on the regular. But we countered with microrebellions. Our model of pain management was Every day a small catharsis. And that first Femmes record was just what the doctor ordered.

Let’s jump back to 1993. Promptly upon learning that the Violent Femmes had accepted our invitation to P-Party, I applied for University Van Driver Training. The reason for this was the Femmes would be staying in a hotel down by Route 1, so that they’d need a ride to and from the show on campus. And I wanted to drive them.

Van Driver Training was a tedious process that, as far as I can remember, consisted of a three-hour classroom session wherein you were told umpteen different ways that you could not, must not, and shall not have drugs or alcohol in a University Van. I passed the test and signed all the required pledges. Duly certified now to reserve and drive a Princeton Van, I waited excitedly for the late-April concert date to arrive.

When it came, I picked up the Femmes at their hotel in the early afternoon, to drive them and their tour bus driver to Dillon for the sound check. Gordon was about five-foot-six and slight of build. He wore a black jacket and black-rimmed hipster glasses. He was super-polite and spoke quietly, when he spoke at all. Seated in between the bus driver and Gordon was his polar opposite, Brian Ritchie, a Sasquatch of a man in a Packers jacket whose booming voice and Wisconsin accent could peel the paint off your walls. I feel like he had an unlit stogie between his teeth for the duration of the drive to campus. The third Femme in those days was Guy Hoffman, who had just joined the band after years drumming for the BoDeans. Guy rode shotgun and was super-friendly, if also soft-spoken.

At some point on the ride over, Brian broke in on my conversation with Guy to declare that the tour bus driver was only a so-so driver of buses, and what made him a most valuable asset for the band was that he knew his way around a liquor store better than anyone in America. Accordingly, Brian said, once I dropped the band off for the sound check, I needed to take the bus driver to Varsity Liquors, so he could spend down their expense allowance on top-line hooch for the road. (The University administration strictly prohibited USG from procuring alcohol for the bands, so the loophole we’d crafted was to write a $600 expense allowance into the contract for them to spend at their discretion.)

I pulled up outside Dillon, handed the Femmes three shitty-looking laminated backstage passes we’d picked up at Kinko’s print shop earlier in the day, and pointed the way toward the gymnasium. Then I drove the bus driver to Varsity Liquors. Now I had absorbed the Van Driver Training deeply enough to understand that I was courting real trouble if I parked a University Van in front of the liquor store. So instead I drove around the block ten times while the driver dropped half a G on the finest booze in The 08544. I did have three minutes of exposure helping the driver load multiple crates of contraband into the back of the van, which had blinkers on in the middle of Nassau Street. We motored off back to the hotel to unload the haul, then doubled back to the gym to pick up the Femmes after the sound check.

Later in the evening I picked up the band and brought them to the show. We had a green room set up for them in the rear of Dillon Gym. Food spread and all that. My freshman roommate Dave was working the front door. Dave was a big guy, a defensive lineman. The Princeton football players had established a student agency, called “Safeguard,” that the eating clubs could hire to provide security at their parties. Given that most of the rabble-rousing around campus on a Thursday, Friday, or Saturday night involved drunken football players, many of us felt that Safeguard was more of a protection racket than a legitimate business. That said, I always felt better at a party when Dave was around (and sober), wearing his white collared Safeguard polo.

Word was out around town that the Violent Femmes were playing on campus, and townies were showing up. This was a students-only event, and Dave was under strict instructions to keep the locals out. He was asking for Princeton IDs, and if a kid couldn’t produced one, he turned them away.

There was a group of no-hope Femmes fans loitering just outside the door. Most of these kids were of high-school age, and as I was only two years removed from those days, I knew exactly why they were so desperate to come see the Violent Femmes. So Dave and I worked out a deal: from time to time he would come up with a reason to turn his back on the door, and during the brief window of opportunity this presented, Glenn and I would motion the locals to slip in, crawl through under the table where the ticket-takers were sitting, and get lost in the crowd inside the gymnasium.

We smuggled a couple dozen kids into the show that way, and I wandered off into the gym. About a half hour before the show started, I was called back to deal with a “situation” at the doors. When I arrived, I found Gordon Gano standing in front of Dave, with his arms folded. Gordon would later explain that he’d slipped out a side door of the building to get some fresh air. That door had locked behind him, so he had walked around front to gain reentry to the building. Dave’s take on the situation: This clown just showed up. No Princeton ID, and he’s showing me this ridiculous fake credential he could have made at Kinko’s.

I told Dave that yes, I could confirm that credential was printed at Kinko’s—because USG had placed the order for it. And the clown he was holding out of the venue was the Femmes’ lead singer and guitarist.

You’re shitting me, Dave said. I’m not, I told him. Gordon let all this play out without saying a word, though he did have a big ol’ grin on his face. Dave let him pass. This led to a fresh burst of complaints from the backed-up locals waiting outside for the next opportunity to crawl in under the ticket table. Why does THAT GUY just get to walk right in? Like I said before: in those days, if the Violent Femmes passed you on the street, you’d have no idea who they were.

One final note, before I close—probably the best summation of my character and identity at age 19 is this: I was the kid who wore the oversized orange Polo rugby shirt into the mosh pit. Turns out that was a lousy decision—for the shirt, anyway.

Known these days to Krautrock fans the world over as “Pink Floyd Glenn” (Apple Podcasts, Spotify).

Here’s a list of acts that performed at Dillon Gym over the years.

Another fantastic blast to the past. I wonder what was in it for Brad and Glenn in letting some “locals” slip through. Was it a selfless act of improving “town gown” relations? Or was there more to the story? Enquiring minds want to know…