There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar trying to make up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening.

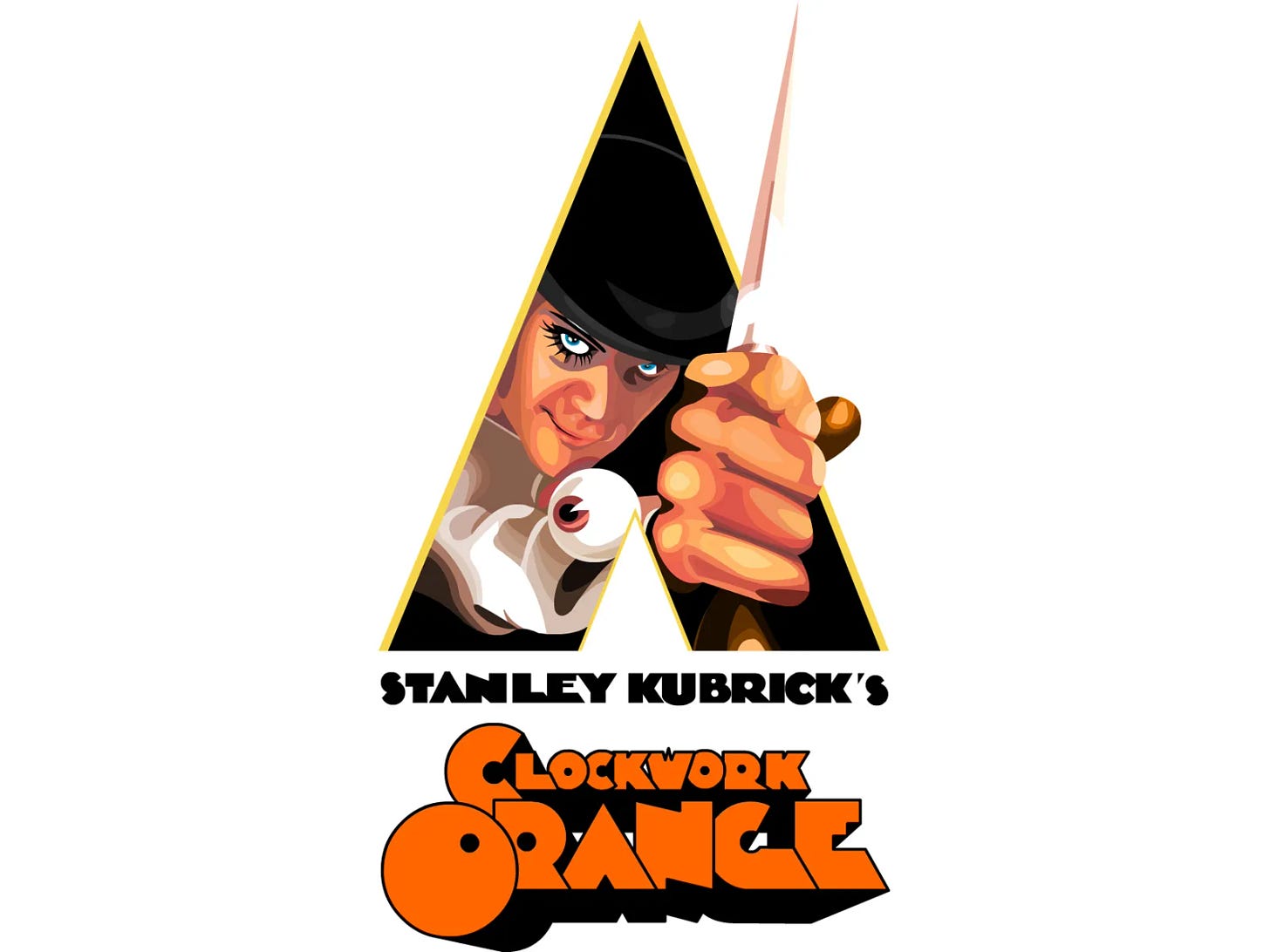

I explained in another post (see “You Are the Everything”/ “Swan Swan H”) that I wrote my senior thesis on A Clockwork Orange. The paper wasn’t per se about the Stanley Kubrick movie; I focused instead on the 1962 Anthony Burgess novella that Kubrick adapted. But let’s be clear: I would never have found my way to the book, were it not for the movie.

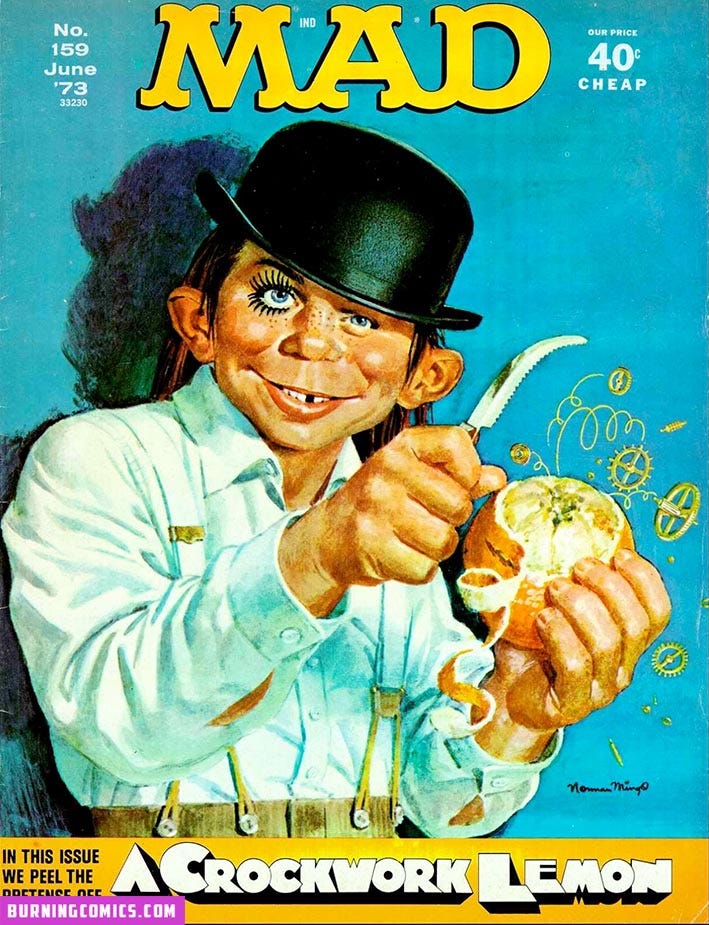

And my first exposure to A Clockwork Orange, the movie, was through the MAD Magazine parody, A Crockwork Lemon, which I read in reprint in 1984. This is how you experience culture, when you’re dropped into The Timeline midstream. The first time you hear “Born To Run” (Apple Music, Spotify), Frankie Goes to Hollywood is playing it (Apple Music, Spotify). Ten, twenty years removed from when a work of art first grabbed hold of the zeitgeist, you arrive checking your watch, and what’s left to you is to register its cultural reverberations and feel your way back from them to the original source material.

The MAD parody made me aware of A Clockwork Orange by title, character likenesses, plotline, and vibe. That is, it gave me enough to have me asking: What’s this all about? From time to time one or the other of HBO and Cinemax—let’s say Cinemax, they were the wilder sibling—would air the movie in the wee hours of the night, and I remember watching at least the first half hour of it a few times as a teenager, on the family room TV after my parents went to bed. Thirty minutes was about as far as it went, the Cinemax guide having warned that it featured adult content, nudity, violence, strong sexual content, and rape, and there was always a possibility Mom or Dad might wake up and bust me watching it.

Fast-forward to college. I had a TV and VCR in my dorm room, and in addition to buying CDs every other week, I was in the habit of spending down a share of my monthly allowance on VHS tapes: the Star Wars movies, of course, but also The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Bugs Bunny Classics, Reservoir Dogs, The Deer Hunter, Dr. Strangelove.

Periodically during the ’80s Dr. Strangelove would air on WUAB Channel 43, and they ran advance promos for it constantly during Indians games. Whenever they came on, my father always laughed out loud—not at the clips they were showing, necessarily, but more generally at the movie he had seen back in the day and remembered. That movie is hilarious, he would say to me, shaking his head. Peter Sellers. And George C. Scott is unbelievable. Channel 43 always referred to Dr. Strangelove by its full title, Dr. Strangelove … or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. As I had only recently learned, courtesy of the breathless hype around ABC’s The Day After TV event (YouTube), about how the “grown-ups” running the world had parked us firmly on the brink of nuclear annihilation for the past two decades—and with no end in sight—that subtitle hit me a bit sideways, so that I had this movie always close to front of mind.

Back then we only watched those commercials together, my father and I, and never the full movie. Not that he would have screened me out, necessarily, as he did whenever Porky’s was on, and Tia and I were pushed to the margins, peering around corners while he laughed raucously by himself in the family room. It was more the case that I was of an age where I was neurologically incapable of watching any black-and-white TV programming for more than an hour. Dick van Dyke Show reruns? Leave It to Beaver? Sure, but a feature-length movie was a bridge too far. So my first dozen viewings of Dr. Strangelove were a decade later, on VHS tape in the college dorms, with friends and hallmates. For all that, when I think of Dr. Strangelove I think first of my dad, then of Slim Pickens riding the bucking bronco of an A-bomb into Armageddon.

Dr. Strangelove was my foothold into Stanley Kubrick, which led me back around, during those college years, to A Clockwork Orange. Back when I was sneaking snippets of it on cable TV in junior high and high school, I did have inklings that this movie was aiming higher than your typical Skinemax flick, even if it was packaged with the same content warnings. The writing, the setting, the costuming, the music [ahem] all signaled in that direction. But it was in college when I first turned on to the idea of directors as auteurs. This was largely due to my friend Mike, who notwithstanding his infatuation with skeevy Southern rock (see “Go Your Own Way”) had exquisite taste in movies and, more importantly, knew something about them. As an example, it was Mike who got me into Martin Scorsese, so that he and I were among the hundreds of students climbing the walls to get into his 1992 campus lecture.1

So Dr. Strangelove made me aware of Stanley Kubrick, and from there Mike was identifying for me what other movies Kubrick had done, in that inimitable way he had and kinda still has: You mean to tell me you haven’t seen THE SHINING?, and so on. A Clockwork Orange was right up top of the Kubrick list, and it wasn’t long before we were all gathered around my TV watching it once a week. And off we went, hallmates and I, slinging quotes from this aggressive, morally challenging art film right alongside the usual fare from Fletch and A Fish Called Wanda.

There was me, that is Alex …

Great bolshy yarblockos to you!

Try the WIIIINE …

The film was so alien and original that it never occurred to me it might be an adaption. But then Professor Showalter assigned the Burgess novella in my Contemporary Fiction class. I was thrilled to find that the book was written in first-person perspective with Alex narrating and for that matter speaking in Nadsat, the Russian-inflected teen slang that Burgess had developed from scratch for this single book. I came to learn, for example, that when Alex and his gang use the term horrorshow to express enthusiasm, they’re borrowing from the Russian word kharasho, meaning good. It’s a brilliantly conceived double entendre.

Around this time I was fixated on the subjects of youth culture and rebellion in Britain. The Sex Pistols were never far from my CD tray, and I was reading up on all the fads and cliques that had sprung up around British music: mods, rockers, punks, rude boys. My senior thesis advisor in the English department a bit ham-handedly suggested I look into the Angry Young Men movement of the 1950s. But that wasn’t what I was looking for. Turned out I really just wanted to write about A Clockwork Orange.

Alex DeLarge was my introduction to the concept of The Anti-Hero, to rooting for the good bad guy. Many more would follow—Beatrix Kiddo, Tony Soprano, Walter White, Tommy Shelby—but Alex was my first. Sure, we all loved Boba Fett growing up, but only because he looked bad-ass and played hard-to-get, in the respect that you had to send away for his action figure. When finally put to the test, though, he misfired his jetpack, clanked into the side of Jabba’s frigate, and Benny-Hilled into the Sarlacc Pit. Pathetic. Alex lacked the Mandalorian bag of tricks, but his low cunning and high style more than compensated. And what was more, he was my age (in those days) and while I didn’t remotely identify with his predilection for gang rumbles, home invasion, and sexual assault, I certainly did share both his contempt for what my elders had made of the world and his earnest desire to transcend them both through art. Or at least artistic pretensions.

I felt all this acutely enough, and I was entranced enough by Kubrick’s production values, that when it came time to put together a costume for Charter Club’s 1994 Halloween event, there was no question I would show up as anyone other than Alex DeLarge. I really wanted a genuine bowler hat, but I didn’t have the money for one, and as we weren’t living in 1919 there were none to borrow around campus. So I went with a cheap plastic model from the costume store where I bought the (also plastic) police truncheon. I borrowed a pair of white sweatpants from my friend Jeff.2 And I got hold of a false eyelash and fumblingly attached it to the bottom lid of my right eye, where it hung by a thread for most of the night, requiring multiple visits to the bathroom to fix.

At some point during the party I ran into a kid from the junior class who was dressed like a West Coast Latino gang-banger, Cypress Hill being hot shit around this time. We stood eyeing each other, two archetypes of adolescent rebellion, and for a minute or two we exchanged threats with forced accents in our respective teen argots:

I’ll fix you real horrorshow. Slash you up with my britva, get the red red kroovy flowing.

Who you tryin’ to get crazy with ese? Don’t you know I’m loco?

And so on, until we realized this playacting was embarrassingly inauthentic and we gave up the project to go shoot pool.

The thesis I submitted in the spring of my senior year considered A Clockwork Orange alongside James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I wrote precious few foundational paragraphs on Burgess’s interest in Joyce3, then dug deep into the two texts to draw out parallels between them. I positioned Alex as a figure aspiring to present himself as unique and artistic, against social conventions and economic tides determined to grind and drag and numb him down into dullness and conformity. The core of his resistance is oppositionality: flout the norms, break the laws, and indulge the base instincts you’ve been taught for years to suppress. But society is no less determinative of your identity and life’s meaning when you choose to do the opposite of what it asks and expects. You’ve cut yourself loose of what, exactly?

And of course looking back on all this work, I realize I was writing as much about myself—about the dullness and conformity I was expecting to find in the wider world after graduation: workaday living, married with children, taxes and death—as I was about Alex or Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus. I couldn’t fully inhabit Alex’s headspace, nor would I ever want to. But I felt I could describe his predicament, his state of captivity, almost perfectly.

An interesting fact about the novella is it has two endings. The first editions published in the United States were truncated: that is, the book ends just as Kubrick’s movie does, with Alex pronouncing he is cured of the government’s experimental conditioning that sickened and debilitated him whenever he felt an urge toward the old ultraviolence. And accordingly, we can expect him to get right back at it. By contrast, in Burgess’s original framing, which at least his UK editors indulged, Alex begins to speak of a desire instead to accommodate himself to society and even fantasizes about settling down, having children, and speaking to them about all the blind alleys his teen self had been compelled to explore.

When I had my son I would explain all that to him when he was starry enough to like understand. But then I knew he would not understand or would not want to understand at all and would do all the vesches I had done … and I would not be able to really stop him.

Arriving suddenly, in the book’s final chapter, this is a real heel-turn. Given the trajectory of Alex’s narrative to that point, it doesn’t make any damn sense, and you can see why American editors and Kubrick in turn rejected it. The government’s behavioral interventions are at least grounded in scientific theory, and in any case, they don’t inside-out Alex’s psyche with the turn of a page. This last chapter smacks of bad writing, even if it’s essential to Burgess’s thesis that focusing on the “clockwork” drivers of human behavior over the “orange”—what is organic and beautiful and God-given4 to us—is morally wrong. It’s clear Burgess was philosophically impelled to tell a story wherein his broken protagonist’s built-in humanity flowers and fixes what the tinkering scientists could not. Points scored here for humanism at a pivotal mid-century moment, but as a literary matter, all this is just too much, too quickly.

Let me be clear, though: I don’t disagree with Burgess’s take. Angry young men do grow up, and if left well enough alone to process their anger, they will find their place and stake in society on their own. (We can put aside for the moment what steps are appropriate to manage the anger in the meantime.) And at least for me, fatherhood did play an important part in that growth. But none of this happens in the revelation of a moment: we shed our grievances over a period of years, like air leaching out of a knotted balloon. Recently on an airline flight I came back to A Clockwork Orange, the movie, for the first time in probably two decades. I think it was on our summer trip to Italy last year. Delta was carrying it in its on-demand movie listings—it turns out what premium cable relegated to the wee hours forty years ago is just fine to watch out in the open now, on your seatback screen. Yet when I fired it up and sat back to take it all in, I found Kubrick’s film, and Alex’s conduct in particular, to be too difficult to watch.

It’s not entirely clear to me what had changed, since I last sat down to watch the movie. Had I gone soft? Was I now so invested in The System that I couldn’t muster empathy with Alex sufficient to overcome my revulsion at his acts of ultraviolence? Or was it just that I was watching him through an altogether different lens: i.e., not as a disaffected youth myself anymore, but as middle-aged man and a father of teenagers? Let’s not dig too deep here. Let it suffice to say I have undergone the very transition and transformation that Alex described, in anticipation, in that last, artistically problematic chapter of Burgess’s UK first edition.

Thus far I’ve mentioned only in passing the movie soundtrack. It is of course incredible and innovative and powerful and played more than a bit role in drawing me in to the story. I mean, look: from the jump this movie grabs you by the lapels, the hair, and the testicles all at once. The first-scene visuals of the Korova Milkbar are something else. Black walls, floors, and ceiling with chaotic white letters on them, nude female mannequins twisted and splayed into service as coffee tables. But even before that, there’s just the opening shot on Alex’s face. Squarely front-facing, in what I appreciate now is the classic Stanley Kubrick style. Eyes rolled back to convey a sense of disturbance, of off-centeredness as Alex begins his voice-over, using Uncanny Valley words that, while strange to us, convey just enough meaning to have us on the edge of our seats.

But even before that, in the very-very-beginning of the film, there’s the title sequence. Twenty-five seconds on a blank blood-orange screen before the Warner Bros. logo appears. Then the screen goes blue, displaying Kubrick’s name on it, before toggling back to orange again to present the title. And played over this, from the first splash of orange, is Wendy Carlos’s apocalyptic arrangement of Henry Purcell’s Funeral March for Queen Mary. Vast, powerful stuff. Futuristic, if you can say that of a 300-year-old Baroque musical composition—and you can, when it’s played on a Moog III synthesizer in 1971.5

I mentioned Wendy Carlos last week (see “Vuh”), when I was writing about Popol Vuh and the Moog III synthesizer. At the time I meant to celebrate Florian Fricke’s application of the Moog to original music, and I’m worried now that in the process I didn’t give Wendy her due. Popol Vuh doesn’t happen without Switched-On Bach. And A Clockwork Orange isn’t what it is without Wendy turning her attention next to Beethoven and Purcell, substituting electronic synthesis for orchestral performance, and processing the chorus of the Glorious Ninth of Ludwig Van through vocoders.

It’s a masterful turn on dystopian projection, this trick. Take existing classical works and refract them through cutting-edge technology so that they, too, are parked in the Uncanny Valley, right alongside the Milkbar set and Alex’s vocabulary. This is a logical extension of our world at the point of the film’s release—our social structures, our philosophy, our science, and our arts. And it’s creepy as hell.

Or better yet: horrorshow.

Another memory glitch: I was convinced I had covered this event for the Princetonian, but the by-line on this article says otherwise, so I must have attended as a civilian. This would explain why I was in one of the overflow rooms watching Marty on closed-circuit TV.

Jeff doesn’t deserve to be remembered for having these in his wardrobe, but I’m not letting him off the hook, either. White sweatpants.

The reviewers’ note tucked in my bound volume, signed by Professors Showalter and Ordiway reads: “[T]his part of the thesis would be even more effective if it provided a fuller documentation and development of the idea that Burgess is ‘obsessed with honoring Joyce’s work.’” Sure. Fine.

Burgess was a devout Catholic.

I can’t remember when or where I saw this movie, but it definitely was in a real larger-than-life movie theater. It spurred me to watch every other Malcolm McDowell movie I could find. Thanks for the nostalgia.