Cable TV didn’t come to Red Oak Drive until I was eight or nine years old. Before that we could reliably pick up three VHF channels out of Cleveland: WEWS, WJW, and WKYC for ABC, CBS, and NBC programming respectively. I don’t remember much about these channels, except that I was terrified of Dorothy Fuldheim. By the time I was watching she was 90 years old and barely upright at the news desk. But still, from that slumped-over position she was getting off shots at any- and everybody, all of whom seemed to have it coming. I read just now that back in the day she interviewed Hitler. My sister used to joke that she looked like E.T. in a red wig.

The Youngstown network affiliates were on the UHF band, which was an order of magnitude more difficult to fine-tune into our living room. The baseball games came through over WUAB Channel 43, an independent station out of Cleveland that was marginally easier to reel in than the others on UHF. Channel 43 had the Indians and Superhost, a local TV personality who appeared on Saturday afternoons wearing an overstretched Superman outfit and blush on his nose. Superhost cued up monster movies and brought the broadcast feed in and out of commercial breaks. And now, back to … GODZILLA VS. MECHAGODZILLA! I remember the night in 1981 Lenny Barker threw his perfect game. Rick Manning caught the Blue Jays’ final out in center field. Now he calls Guardians games on (for now) Bally’s Great Lakes.

We had a TV antenna mounted on the roof of our house. On top of the TV console in our family room was a panel with a dial on it that you could use to reposition the antenna. The dial had stickers on its face marking the best position for each channel. If I recall correctly—and I’m not sure I do—the TV console was made of green-stained wood. The console was at floor-level, dropped down on the olive shag carpet. It doubled as a piece of furniture. We had framed photographs on top of it, arrayed around the dial tuner.

My grandparents got cable television before we did. When we first visited after the installation Grandma Helen showed me how to operate the slide-channel remote box, and she steered me toward Nickelodeon. Then she left the room to make a batch of her signature macaroni and cheese, to be served with bread, butter, and boysenberry jam—or so I like to think, when I remember this day and all others at Old Orchard Drive. In the moment, I was pretty jazzed about Nickelodeon. A channel entirely for kids! And not just for three hours on a Saturday morning, or an hour on Sunday night if the football games didn’t run long, but all day long. This was promising.

Forty years later I couldn’t tell you anything about Nickelodeon’s programming, other than that Alanis Morissette was an early regular on You Can’t Do That on Television, and if at any point she or another cast member uttered the words I don’t know in the main studio, they’d get a bucket of green slime poured over them. What else Nickelodeon aired all damn day, I have no idea. But I could describe to you easily a hundred videos—audio and visuals—that ran on MTV during the same time period.

I don’t exactly recall finding my way to MTV, but it’s not hard to imagine how it could have happened: Nickelodeon cuts to commercial, and I start channel-surfing. Down at that end of the slider box was TNN, the country-music station. Moving right along from that in a hurry, I would have found ESPN, a channel devoted to sports, but still lean and mean in those days and capitalized at a level that could only afford the broadcast rights for stuff like Mesquite Rodeo and Aussie Rules Football. These were fun as hell to watch—possibly on the merits, and possibly, too, because they pointed to a world outside the NBC/ CBS/ ABC monoculture. And there was the TBS Super Station, which ran Looney Tunes, Tom & Jerry, and The Andy Griffith Show during the day.

It seems likely I would have landed on MTV during one of the rocket-launch promos. That would have grabbed me by my kiddie lapels and shaken me silly. The blastoff, the astronauts on the moon, the dazzling colors cycling through the MTV logo—count me in. Forget the green slime and the calf-roping and Road Runner and Opie. I wanted my MTV.

As best I can remember, the first music video I ever saw, in that TV room on Old Orchard where I go so often in my dreams these days, was “I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)” by Hall & Oates (Apple Music, Spotify). Not one of the ’80s new wave classics—not “Our House” (YouTube) by Madness or “New Song” (YouTube) by Howard Jones or even “Fish Heads” (YouTube) by Barnes & Barnes. Alas, my first introduction to the music television concept was Hall & Oates. Yet as I watch that video on YouTube now, for the first time in probably four decades, I’m thinking Yeah: I probably COULD go for that.

Not long after I got hooked on MTV at my grandmother’s house, arcane symbols began to appear four miles away on the streets of our neighborhood. Garbled letters and arrows, spray-painted orange on the asphalt, communicating unintelligible messages. We never saw who left them; we just came home from school one afternoon and they were there—like something out of an H.P. Lovecraft story, or the Toynbee tiles I saw stamped into streets across Manhattan in the late 1990s. But these inscriptions weren’t forecasting rebirths on Jupiter, nor were they markings made by, for, or heralding Cthulhu. My dad explained over dinner that the dig crews had made them, because Community Access Television—that is, cable TV—was finally coming to our subdivision.

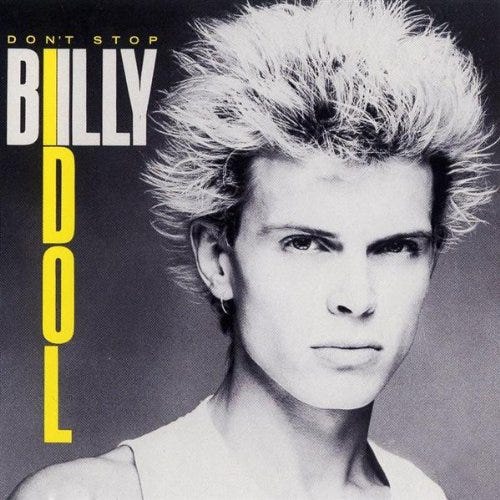

I’ve written a bunch already about MTV in this Substack, and I’ll have loads more to say on the subject before I’m done. Hell, I could probably give you 10,000 words on Martha Quinn today, advancing and proving the proposition that she was the single most adorable and necessary person on Planet Earth between 1981 and 1986. I could write about the contests: Asia in Asia, People really win on MTV!, and so on. But today I want to talk about a particular music video that, at least for me, defined the arrival of cable TV, and that’s Billy Idol’s “Dancing with Myself” (Apple Music, Spotify).

Billy’s been lurking around this site for a while now, having earned mentions in my Februarys and Siouxsie posts. (See “Any Wednesday” and “Helter Skelter,” respectively.) I suppose this is because arriving when he did, with the splash and splendor he did, Billy Idol became a kind of archetypal figure for me. Of the thousand characters MTV surfaced in that split-level family room on Red Oak Drive, I thought his (and Adam Ant’s) were the coolest. The way he spiked his hair, curled his lips, punched the air—bad-ass, all of it. And let’s be clear: everything I’m not. The other day I was out for a run listening to the Tony James interview on Rockonteurs (Apple Podcasts, Spotify). Tony and Billy were of course founding members of Generation X, and Tony recalls pre-punk Billy as a bookish university student, scrawny and bespectacled and reading philosophy.

It turns out there was hope for me to take a hard left turn and become a rock star. Why am I only finding this out now?

The first time I saw or heard Billy Idol was in his “White Wedding” video (YouTube). At the time, I thought he was a metal act. All the dark imagery—nails hammered into a coffin, Billy singing among lit candles, crosses everywhere, the wedding band tearing the skin off the bride’s knuckle. And that’s not to speak of the ending, where said bride is entombed in a spider’s web, with Billy dominating the foreground. Gothic, certainly—and the song sounds more like Judas Priest than punk rock. Not that I knew what punk rock or Judas Priest sounded like, at the time.

“Dancing with Myself” was an earlier recording, co-written with Tony James and originally released under the Gen X banner. The Generation X version is the copy I own, from their Perfect Hits compilation, which I bought on CD fifteen, twenty years ago. The Billy Idol and Gen X versions sound super-similar but not quite the same, and it took me a minute this week to get to the bottom of what happened. Turned out they’re mixed from the same session recordings, with the Sex Pistols’ Steve Jones on guitar. The recording credited to Billy Idol was released on an EP called Don’t Stop, after the Generation X single failed to perform as expected in the UK charts.

For the life of me I can’t see why “Dancing with Myself” wasn’t a global #1. If you’re not in on this song after the first ten seconds with the drums, the guitar alarums, and then the stuttering monotonic bass … well, I don’t know what to tell you. You’re in the remedial class: go back to the beginning of this Substack, and I’ll see you again in fourteen months. I’m jamming this over my computer speakers as I type, and while at first I couldn’t find the Steve Jones in the mix, boy, oh boy am I hearing him now. Starting at 1:10, and kicking into second gear with the solo at 1:30, it’s the Pistols all over again, but dished out with a sharpened pop professionalism neither Marketing Malcolm nor Rotten John would ever have stood for.

But let’s talk about Billy, and how he nails the vocals here. His voice is most definitely a baritone, but with just a touch of South East London and a sneering edge to it. I wonder if Oh! Oh! Uh-oh! featured in the song as written or he developed it in the studio. However it made its way into the mix, there was nothing more essential to early MTV—and to a certain 9-year-old kid slack-jawed on shag carpet watching it—than that non-verbal mantra.

The video is 1980s excellence, in so many ways. It has the rudiments of a story: Billy is on top of a building in a wrecked, post-apocalyptic city. He’s rocking out by himself—dancing, and singing, too. Gathered at the base of the building are a dozen or more unwashed dancers. Their hair, makeup, and moves would have placed them at any of the several New Romantic clubs dotting London in 1980. Blitz Kids, before the bombs rained down. Now they’re filthy and their clothes are in tatters, but they still have spirit. They claw and scrape up the side of the building, at which point Billy—who thus far has been declaiming about how he would ask the world to dance, if he only had the chance—grabs hold of two electric coils and zaps each and every one of them off the building with his eyes.

Down, down, down the Blitzed Kids fall to the rubble below. They survive the landing, climb right back up again, whereupon Billy honors their stick-to-it-iveness and allows them to dance the night away with him, up to and through the fadeout. It’s really an ode to perseverance, this video. You, too, can hang with Billy Idol, so long as you’re able to overcome 10,000 volts to the face and a hundred-story drop onto hard pavement. Or it could be the battery charging those coils only had one round of zaps in it. In any case, it’s a happy ending for all concerned. Except …

There’s all this other stuff dropped into this video—none of which, as far as I can tell, has anything to do with the main plotline. We’re afforded a glimpse inside the living room of a family of four: the two kids are practicing kung fu moves, and the father is dancing gleefully behind his wife (seated on the couch) with a sledgehammer in his hands. Oof. How does that end? Well, you’ll never know, because that’s the last we see of these people.

In another room, we see the silhouette of a woman in chains, and in the foreground a Lou Reed/ Lou Ferrigno-looking guy is sharpening some kind of tool on a strop. Now here’s the thing: I’ve watched this video at least a hundred times over the course of my life and I have no memory of ever seeing this man before. I do remember the girl, because I’ve wondered: is she the woman in the tattoo on Billy’s left bicep? If not, why the cut from the woman to the tattoo? Why the cut from the tattoo back to the woman later in the video? And where did Lou/Lou go? Is he still menacing the woman?

This is to say nothing of the animatronic skeleton and papier-mâché duo yukking it up in the parlor room in the next cutaway. Talk about freaky. Really: what’s happening here? What do these three comically disturbing inserts have to do with anything else that’s happening in this video?

But hold on: on closer examination I think I just figured this out. Billy doesn’t start out on the roof. The video opens with an exterior shot of the building, and with the first stroke of the snare drum, a light flashes on in a window several floors below the roof deck. Then it cuts to Billy walking into what I understand now to be an open-door elevator. Now he’s going up, but slooooowly—it takes all the first verse to get there—to the roof. You can tell he’s on the climb because the background behind him is slooooowly dropping down. These three seemingly disconnected tableaux are what he sees through the metal grating on the way up. It’s only at 0:55 that Billy steps out onto the roof deck, and yet I’d carried in my mind that he was always there.

Kinda wild that I’m only piecing this together now, but in a way it makes sense. So much of early MTV was random striking images, thrown together without rhyme or reason—you took it all as it came. A Billy Idol video came on, and 3 minutes and 23 seconds later it was over. You couldn’t run it back for close, careful examination of its narrative arc—well, you could, if you managed to catch it on VHS tape, but good luck1—and so you tended to let it wash right over you. And for that matter, if the song had you up off the couch doing the pogo and singing along, you certainly weren’t going to pick up minute details about the overall composition.

But hold on again: I just watched the video downstairs with Lila. I’d explained to her I had just cracked the code and Billy Idol was riding an elevator past a bunch of psychos in his apartment building, and I wanted to show her. We sat down and I cued up the video on YouTube, and she instantly pegged the rabble-rousers at street level as zombies. Well that just threw me for a double loop: was Billy justified in zapping them off the rooftop patio? Did they mean him harm in the first instance? And if that’s the case, did Electric Billy charge them up with better intentions, so that after they made their second dogged climb to his level, they opted to party with him rather than, I dunno, eat his brains?

Oh, and now I just caught this: the pullback shot at the end of the video reveals a billboard, on the roof, showing the girl in Billy’s tattoo. The plot thickens further still.

With every rewatch I feel like I’m getting closer and closer to the bottom of this story. And with every rewatch I get completely jacked watching Billy jump-punch that swinging lamp (time-stamp: 2:39). This song and this video make me want to run up Pearl Street overturning cars with my bare hands. That’s what Billy would do, for sure. As for a guy like me in middle age, with rickety limbs and a generally conservative attitude about public order offenses, it should be enough just to rock out here in the guest room, in my wheely desk chair.

If I had the chance, I’d ask the world to dance—and not be dancing with myself. When there’s nothing to lose, then there’s nothing to prove, and now I’m dancing with myself.

Oh! Oh! Uh-oh!

For a brief discussion of the complexity of real-time recording select content in live broadcasts, see “You Spin Me Round.”