I’m writing this post before and after a Depeche Mode concert I saw/ will see Friday night at Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse, in downtown Cleveland.

My first “without parents” concert was a Depeche Mode show at Blossom Music Center in May 1988, during the spring term of my ninth-grade year. Mode was touring on their Music for the Masses record, but because I was super-cool even in those days, I was actually attracted to Blossom that night for the opening act, which was Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. Like most anyone else Stateside, I had discovered OMD through the “If You Leave” (Apple Music, Spotify) single they recorded for the Pretty in Pink soundtrack two years earlier. I’d since gone out and bought their latest studio LP, The Pacific Age, on cassette and eagerly snatched up a greatest hits comp they released shortly after that. Over a six-month period I wore that Best of OMD cassette down to the nubs. I was not going to miss an OMD show.

Some 35 years later I would learn, from Andy McCluskey himself at an OMD show here in Boston, that Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark are at least partly responsible for the formation of Depeche Mode. Vince Clarke had told Andy that after first hearing “Almost” (Apple Music, Spotify), the B-side to OMD’s first single, he decided to sharpen his musical focus and use synthesizers exclusively. Not long after that he had recruited Martin Gore, Andy Fletcher, and David Gahan into the project.1

I was already aware of Depeche Mode, because of “People Are People” (Apple Music, Spotify), which was their U.S. breakthrough hit and “If You Leave” equivalent. I used to carpool with a girl named Cheri from Warren to Youngstown for school (see “Your Time Will Come”), and she had an older sister who was into alternative rock before any of us knew what it was. Cheri had played “People Are People” in the car for me. I remembered liking the music, but the sentiment expressed in the lyrics turned me off. It was preachy and simplistic. I can’t understand what makes a man hate another man—help me understand. I hadn’t appreciated that the singer’s naïvete was a put-on and rhetorical flourish of its own, not unlike what John Lennon did with “Imagine” (Apple Music, Spotify), but with an uptempo industrial pipe-banging beat tacked on, so you could dance to it.

Three, maybe four years later I would first hear the album version of this track (Apple Music, Spotify), on DM’s Some Great Reward. Attached to that mix of the song is a coda that changes everything. The beat drops out, and the synths decelerate into a minor-key slog toward a final, despondent chord. It’s as though Dave and Martin’s sparking lyrics—their urgent, repeated asks that someone, anyone show cause why human beings can’t live together in peace—hit the open air, push forward as long and as far as they can, and are finally extinguished. Cynicism wins, in what amounts to a first-round TKO.

In any case, we were all familiar with the radio edit of “People Are People,” but that song’s radio play was the beginning and end of what we knew about Depeche Mode. One of my friends—Hans or Steve, as I remember—was advised that our best bet for getting quickly up to speed for the show was to grab a copy of their then-current hits compilation, which was Catching Up with Depeche Mode. It turned out that DM would play comparatively few tracks from Catching Up at Blossom. Nevertheless, that show was eye-opening.

OMD were terrific. They played the entirety of the Best of record, starting with “Tesla Girls” (Apple Music, Spotify), which we could hear from a distance while the ticket takers were processing us through the turnstiles. After their set we roamed around the venue site, people-watching. Northeast Ohio’s Goths were out in full force. There were couples promenading in Victorian formal wear: black suits and yellowing bridal gowns. Lots of black lipstick and eye liner. The sun went down, a suitable amount of time passed, and the venue turned down the lights, drawing our attention to the as-yet empty stage.

The intro music for that tour was “Pimpf” (Apple Music, Spotify), a haunting instrumental in 6/8 time that gathers tracks and builds to a massive crescendo over the course of its five-plus minutes. Two minutes into the piece, a chorus joins the mix chanting unintelligible Crowley-esque syllables. It’s a real occult ritual freakshow. If any of us had bought Music for the Masses before the concert, we’d have recognized “Pimpf” as the last track on the record. As we hadn’t, this processional took us completely by surprise and was all the more impactful.

(As I wrote that last paragraph it occurred to me for the very first time that the title “Music for the Masses” might have been intended as a double entendre. A song like “Sacred” (Apple Music, Spotify), with its religious overtones, certainly fits within this designation, whereas “Pimpf” is very much music for a black mass. I’ll have to ask Martin Gore about this next time I see him.)

On the record, “Pimpf” swells louder and louder and louder, into a wall of sound, and at its climax, the bottom just drops out of the song, leaving the listeners in dead silence. When this happened at the show, five massive banners unfurled from the rigging over the stage, and as if by magic the band members were just … there. A snare drum was struck twice—loud as thunderclaps—and the driving synth-bass line for “Behind the Wheel” (Apple Music, Spotify) kicked in. You can hear this sequence on the soundtrack to 101 (Apple Music, Spotify), the concert film Anton Corbijn directed for the Masses tour. But to get the full effect of it, you need to have heard it (1) outside, (2) just after sunset, (3) at 120 decibels, (4) standing with your three best friends (5) in a sold-out crowd of 4500, (6) some 30% of whom were or were dressed as vampires.

This was the day I first learned what a rock star was. Don’t get me wrong: I had been watching MTV for years. I’d seen Joe Elliott in his leather pants and Union Jack T-shirt belting out “Photograph” (Apple Music, Spotify), and I’d seen Angus Young duck-walking in his red velvet schoolboy outfit. But it wasn’t until that DM show that I understood what rock stars are, which is bigger than life, and what they do, which is to leave you completely in awe.

I get how that sounds. On rock’s family tree, Depeche Mode are Kraftwerk’s grandchildren. It would be at least another year before Martin Gore finally reached for a guitar, to write and record “Personal Jesus” (Apple Music, Spotify). At this point they were still three men with short hair standing at synths, with a lone roving vocalist. The metal heads back at school (see “Fairies Wear Boots”) always had choice words for synth-pop acts, and they may have had a point: Depeche Mode started out with strong boy-band tendencies. Watch this clip, and see if you can guess where Rick Astley copped his moves (and haircut):

But even in those early days, for every pop song like “Just Can’t Get Enough” (Apple Music, Spotify), “See You” (Apple Music, Spotify), or “Everything Counts” (Apple Music, Spotify), there were moodier and more challenging tracks like “Photographic” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Leave in Silence” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Pipeline” (Apple Music, Spotify). You wouldn’t have heard any of the latter from the Wahlbergs or New Edition. And shit got darker still as time wore on.

By the time my gang and I looked in on Depeche Mode at Blossom, I was already neck-deep in the aforementioned OMD, along with Pet Shop Boys, U2, and INXS. Please, The Swing, War, and The Joshua Tree were every bit as regular in my Walkman as my OMD cassettes. But ultimately it was Depeche Mode that really accelerated me—all of us, really—down the alt-rock path. And in contrast to these other stalwarts, Depeche Mode felt just a bit illicit at the time. Like they were bad influences: forbidden fruit I should be careful biting into. Of course this is laughable now, but for a kid in the suburbs in Ohio who was scared as hell about ever putting a foot wrong, songs like “Blasphemous Rumours” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Master and Servant” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Fly on the Windscreen” (Apple Music, Spotify)—all singles on the Catching Up compilation—broached mature subjects that I didn’t expect my mother would want on the docket. E.g.:

I think that God’s got a sick sense of humour, and when I die I expect to find him laughing.

Domination’s the name of the game—in bed or in life, they’re both just the same. But in one you’re fulfilled at the end of the day.

Death is everywhere. There are lambs for the slaughter, waiting to die. And I can sense the hours slipping by.

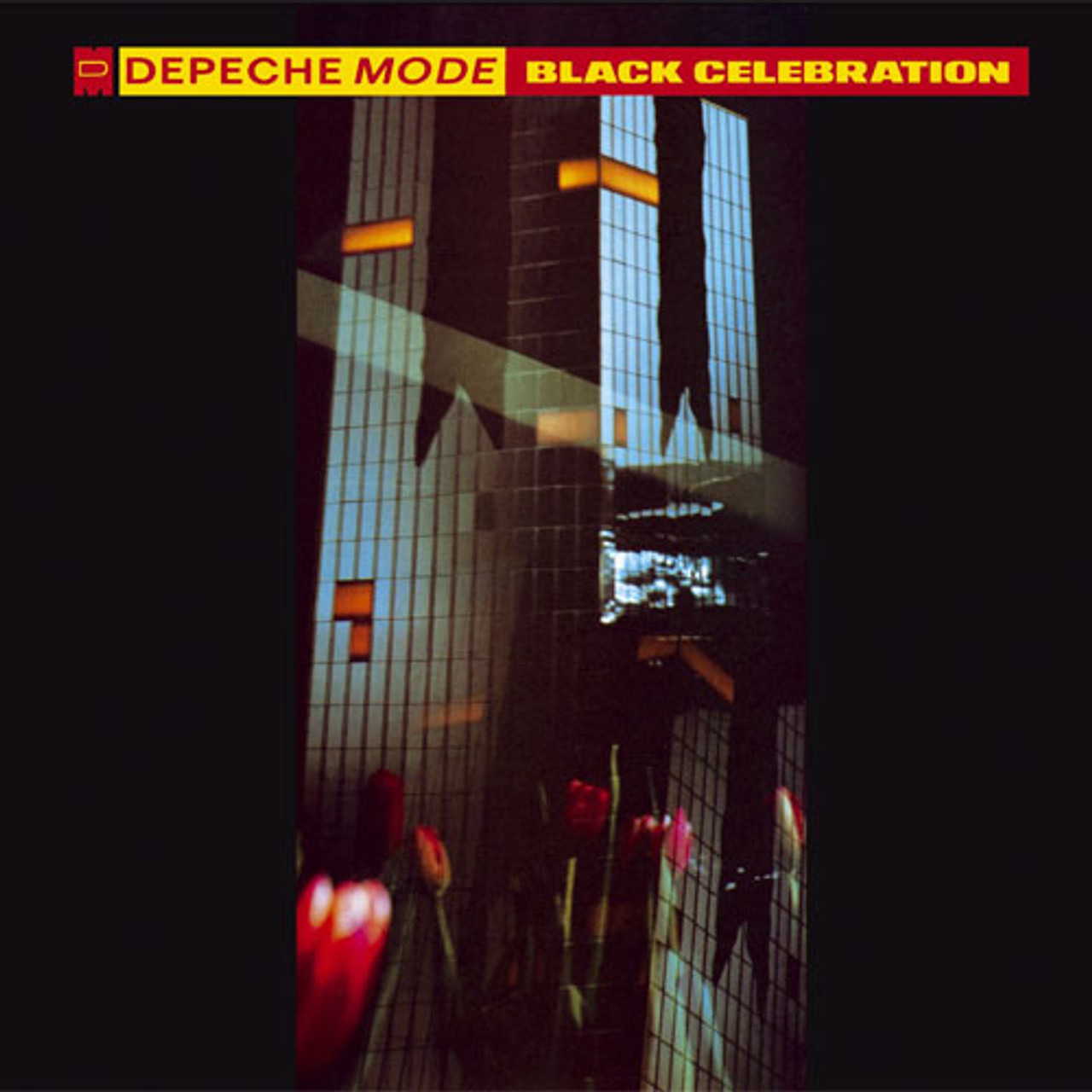

None of this would have sent Tipper Gore to DefCom One, but still I was careful to drop the volume when my parents were home and these tracks were playing in my room. Depeche Mode were sexually ambiguous, wore bondage gear, and a critical mass of their fans were at least Goth-adjacent. To be sure, they were on the Goth 101 syllabus, whereas mid-career Cure were reserved for the 301 class and Siousxie, the Sisters of Mercy, and Bauhaus were the stuff of graduate-level study. You couldn’t even find Bauhaus in any of the record stores within our reach. Yet for several years after the 1988 show I held off buying the record called Black Celebration. I was self-policing, slow-rolling my progress down the path to rock ‘n’ roll perdition. If I weren’t careful, it could be me dressed like a Dickensian London undertaker the next time Mode came through Cleveland.

As I look back on those days now, this apprehension I carried around with me—should I or shouldn’t I get in deeper with Depeche Mode?—reads as at least overwrought and possibly cracked. But it’s important to remember the environment we were living in. In the 1980s, everything worth doing was cast as the thin end of some terrifying wedge or another, and America’s children were out on the front lines. The Satanic panic was on, and public officials were warning, without irony, that rock music led to occult fascinations that in turn led to ritualistic homicide. And if anyone over 14 gave you a temporary tattoo shaped like a blue star, it had un-fully-metabolizable LSD in it that you would carry in your brain for the rest of your life.

We all watched the After School Specials. The take-home from each and every one was that it took no time at all to get in too deep. In this particular case, 27 minutes was enough:

This terrifying shit was on broadcast TV before dinner. I watched it when I was seven years old and I had nightmares for weeks. Presumably other Gen Exers weren’t as scarred by this as I was, but I write today with virtual certainty that Dana Hill’s voodoo blood pool planted the seed in my mind that had me asking ten years later, as I plunked down $15 of lawn mowing money at National Record Mart for a copy of Black Celebration:

What slippery slope am I getting on here?

It turns out we covered this already, in “Four Score in Seven.” Five years after that concert at Blossom, I was screaming FUCK YOU I WON’T DO WHAT YOU TELL ME over and over and over in a Columbus nightclub. By that time I wasn’t looking back: rock ‘n’ roll forever. [throws devil horns] And by “rock ‘n’ roll” I mean teeny-bopper bleep-blip synthesizer music played by quiffed Brits and drum machines, with just the slightest bit of a licentious edge to it.

The song I chose for today is the title track of Black Celebration (Apple Music, Spotify), which for me was the highlight of the show this weekend. The slow-build intro filled the arena to the brim, and my only complaint was that the amps weren’t ten—one hundred—one thousand times louder.

Dave Gahan’s vocals in this song broke my heart when I first heard them in the late 1980s:

I look to you, how you carry on—when all hope is gone. Can’t you see? Your optimistic eyes seem like paradise to someone like me. I want to take you in my arms, forgetting all I couldn’t do today.

Through the decades those cracks have filled in, but sure enough I felt more than a few twinges in my chest, just up under the scars, when Dave—a much older man now, with facial features converging on Eugene Levy’s—went back over this same territory with me.

I don’t listen to Depeche Mode a ton anymore. Sometimes I’ll go months without them, and there are a few albums I’ve set aside for years, so that certain of the deep cuts I’ve all but forgotten. What I will never forget is the hold so much of their music had on me and how deeply embedded they are in who I am, to this day. The early returns on Facebook show that quite a lot of folks I know from the old days made their way to Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse for the Mode show Friday—and some traveled long distances to get there. For those of us chasing memories, old scraps of feeling, and maybe even the traces of a lost sense of community, this was a Black Celebration we couldn’t miss.

Clarke would leave Depeche Mode after their first record, to form Yazoo (in the U.S., “Yaz”) with Alison Moyet. Two LPs later, he departed yet again, this time to form Erasure.

I wish I would have been up to seeing Depeche Mode at Little Ceasers Arena in Detroit, I had tickets in the suite. But, health issues get in the way. It was going there or not going to work next morning. And when the CEO invites, not a good look to miss work for a concert!