Supergrass, "Alright"

I’ve spent the last half hour trying to find my twelfth-grade English teacher online, with no luck. It probably doesn’t help that his name is the Hungarian equivalent of John Smith. Laszlo Farkas taught at Howland High for just one year, as part of an international exchange program. This was the 1990–1991 academic year, not very long after Hungarians ditched Soviet-supported communist rule for democracy, a development that I assume made the teacher exchange possible. Bald with a black beard and a paunch, Mr. Farkas was a lovely man and a lively storyteller. His side stories about life behind the Iron Curtain were eye-opening—probably more important to us, in the long run, than any of the course content he taught. And that’s not to knock him as a teacher.

The reading for that English class was intensive. The syllabus called for us to finish a novel every two to three weeks. We weren’t deep into the year before we learned that Mr. Farkas was a serious film enthusiast. He was desperate to show us the Buck Henry/ Mike Nichols production of Catch-22, which we had been required to read over the summer. He wasn’t wrong. An ensemble cast with Orson Welles, Anthony Perkins, Bob Newhart, Martin Balsam, Art Garfunkel, Martin Sheen, Charles Grodin, and Alan Arkin as Yossarian—that was a terrific watch.

The problem was, we were a class of opportunists, and afflicted with senioritis on top of that. Upon learning of Farkas’s abiding love for The Cinema, we pounced. We took turns making runs to the several video rental shops around town, pulling VHS copies of movies to watch during class. Could be my memory is embellishing this, but I think we even had signup sheets for this. Ideally we could find a straight film adaptation of the book we’d been assigned to read—easy to get Farkas to buy in to playing it, and the movies were better than Cliff’s Notes, if you hadn’t finished the book (or started it). But in a pinch, when we could find no Heart of Darkness movie on the Blockbuster shelves, we were even able to talk Farkas into screening Apocalypse Now. We wrung at least three full class periods out of that one.

One day Mr. Farkas started talking about a book called Tristram Shandy. The first of the English novels, he said. Brilliantly conceived, a forerunner of late 20th century post-modernism, and incredibly funny—so much so that he cracked himself up just thinking about it. Filling the room with his own booming laughter, when none of the rest of us were in on the joke(s). He identified the author as Laurence Sterne, an 18th-century Yorkish parson. Mr. Farkas said he hoped we’d be able to read Tristram Shandy in college.

Looking back, I don’t know how Farkas got on this subject. It’s hard to see how the class discussion could have turned him in the direction of Tristram Shandy. Could be he was at home the night before, his eyes passed over the the spine of his copy of the book, and he made a mental note to recommend it to his students the next day. And come to think of it, that does sounds like him: always looking for cultural treasures he could share with the few dozen American teenagers—knuckleheads for sure, but with the potential to grow into art-loving human beings—who populated his English Lit classes.

I liked Mr. Farkas a lot, and I respected both his taste and his sense of humor. If he dug the Tristram Shandy book so much, then I expected I would, too. So off I went looking for a copy. It took some time, but in the end I was able to find a Penguin Classic paperback edition. It turned out the complete title was The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (Amazon, Project Gutenberg). I remember sitting on our back deck on Springwood Trace, reading with a finger in the back of the book, so I could check each of the many annotations as I went along. There were dozens and dozens of these footnotes,1 dropped by the editors to explain long-lost references. Tristram Shandy was very much of its time, packed to bursting with shout-outs to then-popular and -influential writers, works, and schools of thought. Most of these are now relegated to obscurity, and others Sterne made up from whole cloth. There are discursions on junk science—the Homunculus!—passages in Latin and French (which I might have been able to translate) and Greek (which I couldn’t). As I pressed deeper into the work I realized I had in my hands an amusement park of a book, a museum of antique oddities, chaos on paper.

I’m going to try now—[deep breath]—to describe this book in two paragraphs. The narrator’s objective is made plain in the title: writing in the first person, Tristram aims both to tell the story of his life and to state his opinions. Over the work’s nine volumes, little progress is made on the autobiography. He makes a good start of it, opening Volume I on the night he was conceived. Yet going forward, few of the stories told involve Tristram at all, and when he does appear, he’s more of an acted-upon prop than a protagonist with real agency. Offhand, I can recount four essential facts about Tristram Shandy: (1) that his parents weren’t sufficiently concentrating at the moment of his conception; (2) that his nose was smashed by the doctor’s forceps when he was delivered; (3) that he was christened with the wrong name; and (4) that as a small boy, a broken window sash slammed down on his penis.

The vast majority of the narrative—if you can call it that—is given over to the comic and moving relationship between Tristram’s father Walter and uncle Toby, two country gentlemen with few responsibilities. Tristram reports that his father was recently retired from the import/ export business, whereas Uncle Toby was on a program of indefinite recuperation from a grievous wound to the groin during the Nine Years’ War. Walter is a voracious reader and determined scholar, but perhaps not discerning enough about his sources, which leads to his embrace of peculiar ideas, more than a few of which are given a full airing in the text. Unable—or unwilling—to set the war aside, Uncle Toby spends his days building miniature siegeworks for reenacting the Battle of Namur in Flanders and, thereafter, several skirmishes in the ongoing War of Spanish Succession. Some additional attention is given to the town parson, Yorick, who appears to be a stand-in for Sterne, and his fraternal order of clerical peers from nearby villages, one of whom is called Phutatorius. We’ll get to him later.

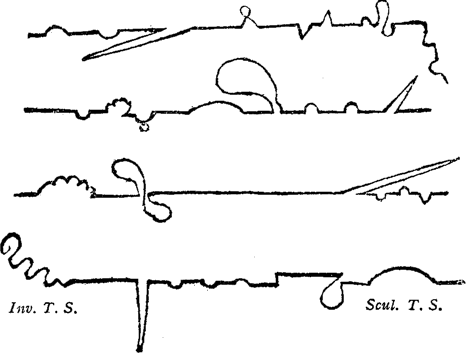

There comes a point—I’d say midway through the book—where a certain incredulity sets in for the reader. You’ve read a sermon by Yorick; a “tale” from Slawkenbergius, the world’s foremost authority, so we’re told, on noses; a Latin curse tablet; and countless disconnected accounts of domestic misadventures from the Shandy family lore, with a hundred-plus stream-of-consciousness digressions scattered in between. In the sixth volume Tristram will offer you a freehand map of the narrative flow of the work thus far, and it looks like this:

So you’re midway through the “story,” with no doubt more of the flabby same awaiting you, and like any reasonable person would, you ask—possibly out loud—the burning question: What’s happening here? Answer: Everything and nothing. Not sure what to do with that, you try another angle: Where is this going? Answer: All over the place and absolutely nowhere. [sigh] One last try: What is all this story about? Here we can draw our answer from the last lines of the book: “A Cock and a Bull, said Yorick—And one of the best of its kind, I ever heard.”

I’m not sure why I like this book as much as I do. Sometimes I wonder if I willed myself to like it, so that I could be the sort of person who could talk enthusiastically about literature with a tastemaker like Laszlo Farkas. And if I did have to put time and effort in to understand, then appreciate, then love Tristram Shandy, how much can I fairly claim really to love it? But I’m going to settle myself down on this point. Love doesn’t always come on at first sight, and to insist that it must is to assign a narrative trope too much authority over how we perceive, and therefore live, our lives. More on this in a moment. The truth is, some works of art are so sprawling, complex, esoteric, and experimental that they don’t flip the switch on first contact. Here’s looking at you, Krautrock.

And in any case, there was a lot to like in Tristram Shandy, straight from the jump. From page one I loved the tone and constitution of the first-person narrator. Tristram is flighty, sentimental, and pathetic, but at the same time glib, witty, and wry. There is no fourth wall here, as Tristram is continually addressing his readers directly. His digressions, his unapologetic apologies for the digressions, his utter disregard of precepts and principles for how storytelling should work—in the first volume he promises, then delivers a chapter upon chapters—all of this is refreshing and fun and, to me, real-feeling. Moby-Dick follows a similarly meandering track, with chapters given over to Cetology and a Wheelbarrow and the Try-Works whaling ships use for boiling down blubber into oil. And of course Melville’s genius floored me, too, because Sterne primed the pump.

It took more time for me, as a 20th-century reader, to understand some of the finer points. There is commentary in here about overlearning, about fake erudition. As narrator, Tristram himself never misses an opportunity to cite obscure texts and name-drop natural philosophers. He most certainly inherited this tendency from his father. Sterne wrote these volumes as the Neoclassical Age was dawning, at a time when not all ideas were equal, and what passed for learning wasn’t necessarily enduring, correct, or even sensible. Hence all the necessary annotations in my Penguin edition. Early on in Volume I, Tristram references Tully and Puffendorf in the same sentence as great ethick writers. Tully—that is, Marcus Tullius Cicero—never goes out of style; his genius, his insights, his poetics are celebrated to this day. But who has ever heard of Puffendorf? Or for that matter Hermes Trismegistus, the fully mystical, quasi-mythical figure regarded by Walter Shandy as the font of all wisdom, after whom he sought and tragically failed to name his son?

There is a certain courageous iconoclasm in suggesting that book-bound arcana are not, in fact, invested with meaning or insight, much less occult powers, and that when thrown open to the world for honest critical review, they may well be revealed to be stuff and nonsense, or Cock and Bull Stories. Or maybe it’s not courageous at all—it’s just we’ve all been ground into dust by Dan Brown books. In any case, I came to admire Sterne’s steady resolve to take nothing seriously. But maybe not nothing, because certain values do shine through in Tristram Shandy—namely: fraternity, generosity, and service. Down whatever blind alleys Walter’s library and Toby’s war games take them, with the other’s help each is always able to find his way back to equipoise. For Sterne, sanity begins, and often ends, at home.

Perhaps more than anything else, I treasure Tristram Shandy for the way it didn’t just disregard narrative form—it destroyed it. Sterne may have been freer to do this, because long prose forms weren’t well-established when he set pen to paper. As examples he had whom? Cervantes had broken through, and Tristram mentions him, but Don Quixote wasn’t, either, a streamlined work with ever-forward momentum. There was no set-in-stone understanding of the shape a novel was supposed to take. No Procrustean beginning-middle-end protagonist undergoes a transformation narrative arc, and no obligation to adhere to Aristotelian dramatic unities. Anything went.

And unencumbered by any existing convention, Sterne went here with Tristram Shandy, with the result that the book reads like life—or better yet, like conversation. The narrative shifts with the winds; it bends toward this attractive notion, then snaps back sharply toward another. You can almost feel the neurons sparking in Tristram’s head as he chases the nearest available distraction. And isn’t that a fair encapsulation of real life, where try as we might to organize our actions and experiences into coherent plot arcs, we’re kidding ourselves thinking there’s any kind of story to tell here? Too often and too unfairly we punish ourselves for failing to mark or chart, much less design and follow, some forward vector toward resolution of our story. So stubbornly committed we are to these narrative conventions that when we can’t make sense of what we see, we suggest a Higher Power is moving the chess pieces, and we’re just too thickly human to grasp The Plan.

I blame Shakespeare for this. And Homer and Virgil and Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. They made us captives of narrative structure. And along came Laurence Sterne to suggest a different, altogether liberating view of the world, where there is no beginning, middle, or end. We slip in and we slip out, and in between we think and talk and laugh and curse in a million different directions, nearly all of which we can find to be rewarding, if we look closely enough. Tristram Shandy could have been the model for prose fiction from the mid-18th century onward, which result in turn might have coaxed us toward a healthier, more attainable and defensible model for living.

Now, instead, we’re trapped. We’re in a literary and artistic space that exalts meaning and economy over all else: where every uttered word and every moment needs to propel a story inexorably forward to its answer. But when I think of a time when a new literary form was emerging, when writers had the option of importing the old poetic and dramatic constraints into it or not—and one of the very first decided he would not—well, that feels exciting for me. Even as I sit here in 2024, in my writer’s chains.

And certainly, too, in the 1990s, when I first read Sterne. I took notes—I thought about the written word and what it could be or stand for. I thought writing like Laurence Sterne might be something I could enjoy and be proud of. And in the popular culture, I did see certain Shandean2 signposts: The Breakfast Club, Seinfeld’s “show about nothing,” the dialogue excursions of early Tarantino movies, in which hard-boiled gangsters rated Madonna records over breakfast. These digressions from the beaten path were exciting, because they chipped out flecks of diamond from mundane experiences accessible to all of us—e.g., what the hell you talk about when you’re sitting in a coffee shop, and how it might be the most urgent and important thing your brain does in any given month.

So yes: I wanted badly to write like Sterne, but in the 20th, then the 21st century. Maybe I never quite got there. Maybe I didn’t have the guts to actually try or the scatterbrained genius to deliver the goods if I had. Certainly today’s world of publishing is not at all hospitable to writing in this style. Now and again a Shandean monograph will slip past the keeper, and a raft of critics will celebrate the goal with songs about the writer’s gifts, nerve, and perseverance. Then it’s back to business as usual: the well-worn tropes and themes—the young woman trying to make it in the big city, the historian drawn into a centuries-old conspiracy, anything with vampires. It’s not literature, we half-apologize, but it’s a good beach read. Because anymore we read fiction exclusively on cabana chairs with fruity drinks in our hands, and good God we can’t be expected to challenge ourselves in that kind of setting. As another prized acolyte of Sterne is wont to say: So it goes.

One thing is clear: my predilection for using the em-dash—for inserting elaborative set-off phrases or even unrelated ideas in mid-sentence, often between subject and verb—is most certainly a result of Sterne’s influence. And again, try as I might to master the art of its use, I am nothing close to the Em-Dash Ninja Laurence Sterne is. There’s no need to run the numbers—Sterne is the most dashing writer in English. He’ll place three of them end-to-end, if he wants—he’ll riddle a sentence, a paragraph, a page with em-dash fire, emptying the cartridge, saturating his own already masterfully composed text with argumentative and stream-of-consciousness dead ends, break beats, and stage dives—and not even the most pedantic Strunk & White stick-in-the-mud critic would dare question the practice. Dash away, Dr. Sterne. Dash away, dash away all.

Some further thoughts about my relationship with this book:

My wife bought me a hardback copy back when we were in college. The inscription reads:

Bradley Abruzzi 1995. Thank you for the thesis help! K.

Hardy and portable, this is my go-to volume, carried around in a backpack on many a long summer vacation—just in case I might need a dose of Captain Shandy and Corporal Trim, or a bit of sophisticated-meets-scatological humor.

My bar trivia gang—we call our team the “Fellowship of the Wing”—bought me a glorious, limited, numbered Folio Society edition for my 50th birthday last September. This from the guys I meet with on Wednesday nights to scarf down pulled pork nachos and two double orders of bone-in buffalo wings, while talking sports and politics and answering questions asked over a PA that not once, to my memory, have touched upon 18th-century English literature. There is always room in this life for surprises. Bill, Glenn, Mike, and Tim: you’re the best.

The 2006 film adaptation, Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story, with Steve Coogan as Steve Coogan playing both Tristram and Walter Shandy, went full meta, departing a good ways from the book to tell the story of a hapless attempt to shoot a feature film about a novel with no discernible plot. A Cock and Bull Story does to film adaptations what Life and Opinions does to narrative prose, and in that respect it earns five stars. It’s also hugely important because it put Coogan and Rob Brydon in opposition, not for the first time ever (they interact briefly in 24 Hour Party People), but certainly for the first time at the center of a film. Cock and Bull set the stage for The Trip and its several sequels, again with Coogan and Brydon playing fictitious and delicious versions of themselves. Possibly my all-time favorite comic duo, and Tristram Shandy (arguably) brought them together.

And finally, there’s Phutatorius, my online persona, my avatar and username on every platform where someone else—and there are others, damn them—didn’t get there first. I took the name from one of Yorick’s consulting clerics, who in Chapter XXVII of Volume IV blurts out a violent oath during a theological discussion on the subject of unraveling Tristram’s christening. Is he upset about the direction of the conversation? No: a piping hot chestnut just fell out of a snack bowl into his open fly.3 Or as Tristram puts it:

[I]t fell perpendicularly into that particular aperture of Phutatorius’s breeches for which, to the shame and indelicacy of our language be it spoke, there is no chaste word throughout all of Johnson’s dictionary——let it suffice to say——it was that particular aperture which, in all good societies, the laws of decorum do strictly require, like the temple of Janus (in peace at least) to be universally shut up.

It’s the best single chapter in all of English literature.

Three thousand words to this point about a book, when my assignment here is to write about a song. Let’s go with “Alright” by Supergrass (Apple Music, Spotify). I’ll own that the song has nothing thematically to do with Tristram Shandy, nor for that matter are they similar in style. “Alright” is short, simple, and to the point—the very opposite of a Shandean work. Moreover, Supergrass are from Oxford, and Sterne studied at Cambridge.

I picked “Alright” because I first heard it in June 1995, days before I made my first pilgrimage to Coxwold, the tiny village—arguably just a crossroads—where Laurence Sterne lived, worked, wrote, died, and is buried. This was part of a three-week tour of the British Isles,4 the first stage of which I spent traveling with Kate. I had flown into Paris on a heavily-discounted US Airways pass, courtesy of my uncle, taking the brand-new Eurostar train through the newly-dug Channel Tunnel to London, where Kate’s parents had rented a flat. After a few days getting my bearings, Kate and I struck out north, to Oxford, the Lake District, and Edinburgh.

It was either in Oxford or Edinburgh that we went out dancing. I can remember what the street, the block, the building looked like; I just don’t remember in which city. In those days, local DJs would rent out big rooms to play the latest indie hits. Or this at least seemed like a common practice, based on the fliers we saw posted around town as we walked. The handbills stated a place and time, alongside a list of the artists you could expect to hear if you showed. I was floored by these lists: name after name after name of bands I loved and that no night-out DJ would ever play Stateside, much less write into an advertisement as an attraction.

The Stone Roses * Pulp* Oasis * Primal Scream * Happy Mondays * Blur * Saint Etienne * Elastica * Suede * Sleeper * Lush * James * The La’s * Keane * Manic Street Preachers * The Chemical Brothers * The Beautiful South

There came a saturation point where I decided I had seen enough of these fliers—we needed to go to one of the gigs. Which we did, later that night. The venue was, as I said earlier, just a big room. Not a pub or a concert hall. Thirty years later I couldn’t tell you if they were allowed to serve drinks. I just remember loud music, a lot of people, and a pretty good light show, given the profile of the event. I knew many, but not all, of the songs the DJ played. Toward the end of the set, he put on “Alright,” and the crowd went nuts. Arms in the air, singing along:

We are young! We run green! Keep our teeth nice and clean! See our friends, see the sights! Feel alright!

Kate and I hadn’t heard this song, and we certainly didn’t know who sang it, but it was the kind of song you could hear and fall in love with on the first listen (again, not Shandean). And fall in love we did.

Got some cash! Bought some wheels! Took it out, ’cross the fields. Lost control, hit a wall! But we’re alright!

I’m decidedly not the kind of person to walk up to any of the hundred punters rocking out to a song and ask them what it is, so I can buy it. That’s not me, first because I’m shy, and second because I’d be admitting that my girlfriend and I are the only people in the room who aren’t plugged in to this essential part of the scene. I’ll do my own research, thanks very much (see “Your Time Will Come”)—these days I can use Shazam, look up lyrics on Google, or in the worst case do the trial-and-error thing on the streamers. None of these resources was available in the moment. I spent at least the next week, maybe longer, going in and out of record stores, rooting through the Featured/ New Release/ Top 20 Album racks, reviewing the track listings for That Song We Heard in the Dance Hall—what could it be called? “We Are Young?” “We’re All right?”

What I wouldn’t have given for an indie-rock Laszlo Farkas to buttonhole me on a Manchester sidewalk and ask me if I’ve heard the new single by Supergrass. It’s delightful. An effervescent, howling update of mid-’60s pop. And oh, those rhythm pianos.

Eventually I did find my way to the right answer. I may just have relented and, with eyes cast down to the floor in disgrace, asked a record store clerk.

Kate and I parted ways in Edinburgh, and I went off on my own further north, to Inverness, Loch Ness, and the Orkney Islands. A week, maybe ten days later I took the train south to York City and hopped a series of buses to the intersection of Thirsk Bank and Husthwaite Road in the Hambleton District of North Yorkshire.5 This crossroads is, for all intents and purposes, “Coxwold.”

There was a village hall, a church—the very church where Sterne presided—maybe a B&B or two. Up Thirsk Bank a few hundred yards from the bus stop stood Shandy Hall, once Laurence Sterne’s house, now still a house, but also a museum featuring a collection of Sterne-related artwork and artifacts, which at least in the 1990s was operated by the residents. Looks like that may still be the case, as the Laurence Sterne Trust website describes Shandy Hall as a “lived-in museum.”

When I knocked on the door of Shandy Hall in June 1995, there was nobody home and the museum was closed. A posted note said the proprietors had gone into town for groceries, and they would be back in a few hours. Their projected return time was after the last bus back in the general direction of York. Imagine undertaking a genuine pilgrimage—to Canterbury, to Mecca—and finding nobody home when you got there. Dejected, I loped back down the country road to the church. I went inside, took some pictures, tried to envision Parson Sterne at the pulpit, giving a sermon. Outside in the churchyard, I found his grave. I sat beside it for a while and listened to the birds—plenty of time to kill before the next bus.

It may have been that same day, or the next, when I found the Supergrass CD. I distinctly remember shopping at an HMV in York. Or maybe I’d bought it earlier in the trip, and I played “Alright” on my Discman while plodding down Thirsk Bank back toward the bus stop. Or I still hadn’t identified and bought a copy of That Damned Song in My Head. However the timing works out, I was either listening to or wracking my brains to find and buy “Alright” by Supergrass during that 1995 trip6 to Coxwold, when I first paid my respects and gave all due props to the genius behind Tristram Shandy.

That’ll be why “Alright” is my Laurence Sterne song, going forward.7

In honor of Laurence Sterne, this will be my most-footnoted post.

This is, in fact, a word (Oxford English Dictionary, Wikipedia). And I will use it more than once here, so suck it up, readers.

That’s three shots to the groin now, if you’re counting.

Could these place names be more English?

I made another run at this in ’98, calling ahead to Shandy Hall before I departed York City for Coxwold. The house was open for touring when I got there, and the visit was worth making two trips to accomplish. Now I just need to get back.

Also, if you squint just right and really think hard about it, that verse about driving off road into a wall is a passable metaphor for my fave author’s writing style.

Love this commentary - (-!) may have to add Tristram Shandy to my reading list.

ps “Fellowship of the Wing” men are awesome!