There’s a two-character dialogue I wrote into New Jersey’s Famous Turnpike Witch, about what traditions mean. Djinn, very much an unsentimental sort, is asking his business partner and friend Virgil what Christmas traditions he will carry over from his childhood, once he’s married with children … and what others he plans to discard.

“What would I discard? Nothing — these are traditions.”

“A tradition becomes a tradition because, on its own merits, it’s worth repeating,” Djinn said. “Traditions lapse when they’re no longer worth repeating.”

“But if you’re constantly reevaluating a tradition, to decide whether you want to keep doing it, then it’s not really a tradition, is it? It’s just like anything else you decide to do.”

“Or not to do.”

This dialogue has its origin in a kind-of-argument my family had one December back in Ohio 25 or more years ago, when my sister asked my father when he was going to decorate the tree in the back yard. My father and Tia had identified a squat little tree on the mound behind our back deck, which they called—I’m writing this phonetically, because I don’t think it’s actually a word—the Chubetta Tree. The Chubetta Tree lived an undignified existence for eleven months of the year. But come December, the Abruzzis strung lights on it, and for at least the Christmas season it took pride of place among its taller, trimmer, unlighted peers.

Confronted with the prospect of sprucing up Chubetta on that particular day, Richard Abruzzi demurred. He was tired, it was cold outside, and he just didn’t feeling like slogging out there through the snow to string lights on Chubetta. “But it’s a TRADITION,” Tia insisted. Ultimately, after some amount of grumbling and muttering to himself, Dad did go out back and light up Chubetta, averting the crisis.

This exchange had me thinking: Aren’t the traditions here to serve us? Do we have to do them if we’re not feeling up to it? And not so long after that, I Djinned up a character to represent that unsentimental side of Twentysomething Me that was asking these questions. And so Djinn made his argument to Virgil, who now I think of it probably stood for another, equally questioning, side of His Author.

It’s been something like 18 years since I’ve celebrated Christmas in Ohio. Since the kids were born, we’ve tried hard to make sure our nuclear family is here at Pearl Street on the 25th. Kate and I want Christmas and home to be tied together in their minds, just as they are for us. We love our traditions here, and as I sit here writing on Friday with so many of them up ahead waiting for me, I am beyond excited. Still, there comes a point every Christmas Day when the dust and packing peanuts settle, I have time and tranquility to think about the holiday, and I ache for those nights and days in Warren, Ohio.

Because it’s not as simple a framing as Djinn makes of it. Traditions aren’t continued only when they’re perfectly enjoyable and easy. I appreciate this now, at age 50, as one of two in the household principally charged with putting in the considerable prep work to deliver on these yearly promises. But it’s important, too, to consider that traditions aren’t discontinued because they necessarily weren’t worth sustaining. Sometimes life just changes out from under the old standards—you get old, you fall in love with someone from out of town, you marry and settle elsewhere (see “My City Was Gone”). I.e., you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife, and you may ask yourself: What happened to those golden days of yore?

My parents—once Mom and Dad, now Grammy and Bappo—winter in Florida now, where my sister lives. We’re of course in New England, and in alternate years we will travel to see Kate’s father in Utah or my family in Bradenton over the holidays, but not until the 27th. Christmas in Ohio is entirely off the table, and if we did take it up again, it would of course feel different, and not year-upon-year incrementally different. Big-time different.

So what I have on the table here with Christmas are experiences that can’t be recast, replicated, or even approximated. I can only try to conjure them up from memory. These memories are precious enough to me that I do iterative, time-set-aside work every year to curate and protect them. I conscript my mind’s eye into service recalling specific sights, sounds, smells, and tastes. I restore entire settings—our kitchen and family room, my grandmother’s house on Wainwood, the sanctuary in Howland Community Church, Cedar’s Lounge—and I place characters in them and move them around, like toy dolls or, which may be more on point for this post, Star Wars figures. By revisiting those times at least once a year, I can make sure that their imprints do not fade from memory.

Our traditions provide a framework and organizational structure for this retention work. If Christmas is a body, traditions are the skeleton, and the experiences are the flesh. Without first attending to and recalling the traditions, any attempt to reconstruct those olden days would leave you lost and confused with piled-up cuts of meat on the floor. I appreciate that this is a grotesque analogy. You could have used a Christmas tree instead, you’re thinking. The traditions are the branches, and the experiences are the ornaments. The truth is I did consider that metaphor, but I rejected it because it assigns too much significance to the yearly agenda and too little to how we lived its bullet points. In any case, I’m not here to bicker with you about analogies.

[ahem]

We always hosted Christmas Eve at our house. Generally speaking we served beef tenderloin, augmented with pasta and fried smelts carried out from the family restaurant. My mom procured the tenderloin from the West Point Market in Akron, an upscale grocery with delicacies unavailable in Trumbull County, a great many of which were on offer as free samples in the store. My friend Brad rode down with us once, and every year after that I made sure to wangle him an invite to come along. We stalked the aisles of that place and ate like kings, one toothpicked bite at a time. Within walking distance of West Point Market was a record store called the Quonset Hut. I found a copy of James’s Stutter (Apple Music, Spotify) there one December, which in the moment was a Christmas miracle not quite at the level of the Christ Child Himself, but it felt close.

My mom used to make a raspberry trifle for Christmas Eve that to this day is my all-time favorite dessert. Not sure if on the merits it’s actually the best dessert I’ve ever had, or if instead its associations with so many treasured nights have boosted it up the ladder past, say, Locke-Ober’s baked Alaska—another bygone delight. One year Mom summarily decided to discontinue the trifle and serve tiramisu instead. She said she wanted to change things up, and that was the end of raspberry trifle. I haven’t had it in probably three decades, so yeah: I certainly have built it up in my mind.

In the ’90s my parents got on a Three Tenors kick, and they had the Christmas CD. It, um, wasn’t my favorite. I still have to laugh when I think of Pavarotti (or whichever one it was) stringing out mee-sull-a-TOE to four syllables over five ridiculous seconds. For better or for worse, the Three Tenors’s Christmas LP is the music I associate with Christmas Eve—along with Brenda Lee’s “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” (Apple Music, Spotify), which was an obsession for my cousin Marlene one year. She grabbed onto me like the Ancient Mariner that night, fire in her eyes, and pulled me into the den to play it on dad’s stereo. Yeah, okay. But it’s not “Merry Christmas (I Don’t Want To Fight Tonight)” by the Ramones.

In attendance on Christmas Eve were grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. I can place my Grandma Helen in our beige reclining chair, smiling sweetly. My Uncle Bob always arrived late, once he was able to break free of the restaurant. Abruzzi’s Café 422 was closed only one day of the year, and that was Christmas Day. On the 24th he was still needed for the dinner shift.

At some point every year, someone—probably Zio—dug our VHS copy of White Christmas out of the cabinet and put it on. Around this time I tended to wander off. I wasn’t into old movies, and especially not old-timey musicals. White Christmas played in our house on December 24 every year for at least a decade, maybe two, during the ’80s and ’90s, and I don’t think I watched more than a half hour of it until a few years ago, when I sat down here and played it all the way through. Mutual, I’m sure was the line that always brought the house down at Springwood Trace on Christmas Eve. I didn’t get any of this. Now I do. But that’s true of literally everything in this life.

We—that is, my parents, Tia, and I—always had to leave our own party early, to go to the 11 PM service at church. The Catholics in the family had Midnight Mass, if they were going, so they had a longer time to laugh and schmooze and tell old stories. I always felt like I was going to my doom, being pulled away from Christmas Eve, before I could eat my eleventh slice of tenderloin. Tia complained, too. The complaints never took. The meaning of Christmas has deeper roots than Danny Kaye and fried smelts, and we needed reminding of that.

That said, as early as we had to leave our Christmas Eve festivities, we were always ten minutes late to church, at least. This was a running joke with the rest of the congregation. Always a grin and a wink from the usher handing us the Christmas service program and our unlit candles. The 11 PM Christmas service was really, really long. I have heard from the Catholic side that Mass—and specifically the walk-up communion—is an efficient enterprise, lean and mean. You get in, get saved, get out. To be fair, they had a fifteen-century head start to work out the kinks. By contrast, our Protestant church served in-pew communion every Sunday, which meant that minister and congregation alike didn’t quite have the walk-up version down to a science, and the Body and Blood took forever to parcel out on Christmas Eve.

No matter: this meant more time for the extended vocal solo, which was assigned every year to the choirmaster’s wife. This instance of small-town nepotism could have been ripped straight from Lake Wobegon, and it played out just like Garrison Keillor would have scripted it. Every year as our soloist trilled and warbled through a vocal arrangement not miles, necessarily, but certainly a yard or two beyond the reach of her talents, my sister would at some point make eye contact with my Dad. They would start to laugh—fighting hard not to, but of course the fighting made it all the harder not to crack up completely. In these moments I always tried to keep my eyes fixed on the horizon, like one does on a ship, when the seasickness is coming. Focus on the pink advent candle behind the altar. Try to melt it with your mind. But at least half the time the situation got the better of me, too. In later years, the settled practice was to put my mother and me in the pew between my Dad and Tia, because having them next to each other was a recipe for disaster during the musical program.

Although the service was long, all of us were worn out, and church was the last significant hurdle to clear before we could access our respective hauls on Christmas morning—a fact that made it feel like even more of a slog—there was an important payoff here. We got to sing Christmas carols, in a group, backed by an organ. The program didn’t include the same songs every year, but “Joy to the World” was posted on the regular, and my all-time fave “O Come All Ye Faithful” cropped up a lot, too. “Silent Night” did feature every Christmas Eve, at the very end of the service. We sang it holding lit candles, our flames drawn from the Christ Candle up front and now passed through the congregation, one to another. That was pretty terrific.

When we got home well after midnight, we would turn on the TV—we were and still are an all-waking-hours TV family—and the Pope would be conducting the sunrise service at the Vatican. Tia and I would finally get to sleep, while more packages materialized under and around our already jam-packed tree.

I always tried to sleep as late as I could Christmas morning, because there was a significant last gating item to opening the presents that I couldn’t control. My mother had—and still has—a strict morning beauty routine. Corners aren’t cut, ever: not even on Christmas. In fact, because cameras are out Christmas morning, it’s as or even more important that all the steps are followed. Every year I would tell her: You’re never more beautiful than when you get up in the morning. I actually believed that—and still do. The problem was I was always making this case for natural beauty at 9 AM on December 25, when she might reasonably have suspected I had an ulterior motive for telling her just how swell she looked, with bedhead and without makeup.

While we waited on Mom, one of us would drive over and pick up my Grandma Helen, and sooner or later we’d have everyone finally in place to start unwrapping presents. By this time I would have eaten about two dozen of the stash of pizzelles my Aunt Lena would have dropped with us earlier in the week. I can’t imagine how many pizzelles Aunt Lena made over the holidays, because we were just one of presumably dozens of recipients and we had stacks and stacks of ’em.

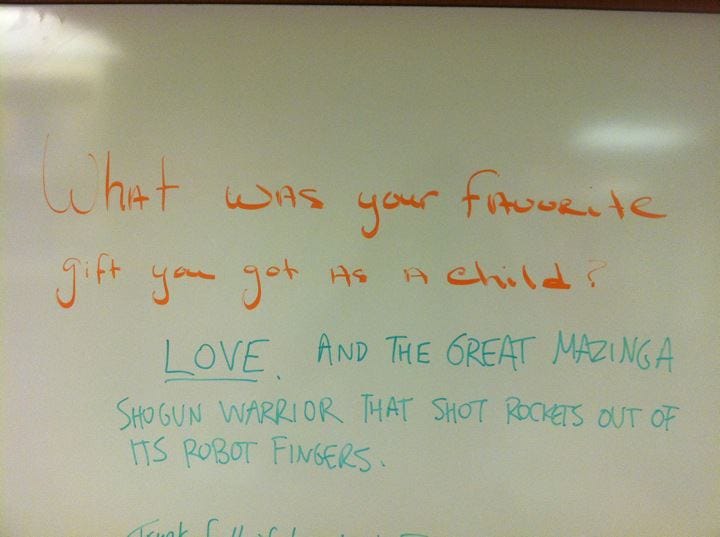

Everyone has their favorite childhood Christmas gift—their official Red Ryder carbine-action, 200-shot, range model air rifle with a compass in the stock and this thing that tells time. Amid the many Transformers, Star Wars figures, GI Joes, and Nintendo and Intellivision games that rocked my Christmas mornings, one gift stands out over all the others. Sure, that first NES system was a prize—so much so that I prevailed upon my parents to let me bring it to my grandparents’ house later that day, because I couldn’t spare a minute of time away from Super Mario Bros. It was fun as hell, too, to get the stereo that one year—all-in-one AM/FM radio, tape deck, and turntable with speakers attached—especially when my sister turned on my parents and said, You got HIM a stereo?, so that I could then say, What is she talking about? It says here this came from SANTA, and then my parents shut her down in a hurry and I ran a big, long, Christmas victory lap in my mind for the rest of the day.

But my all-time favorite Christmas gift from childhood was without doubt the Great Mazinga Shogun Warrior I found under the tree, back in our house on Red Oak Drive, when I was six.

This was before some asshole lawyer (or two) brought a lawsuit and the toy companies took all the springs out of their shooting toys for a six-year period in the 1980s. The rockets actually shot out of Mazinga’s knuckles. And he had a brain condor—a bird-shaped spaceship that nested in his head. Other kids had Raydeen, who if you turned him sideways looked kind of like a hawk. Raydeen is to the Transformers as the Velvet Underground is to punk rock. But the Great Mazinga was the top-brass: the leader of all the Shogun Warriors, or at least of the two I could name then (and now).

Mazinga was the best.

Christmas mornings in the house were busy affairs, for sure, but we always had choral music playing in the background, to set the tone and keep us grounded. As far back as I can remember, the Harry Simeone Chorale’s Little Drummer Boy LP was the soundtrack of the morning. While space-age plastics and high-tech AV equipment blasted out from under wraps into our hands, soothing songs like “O Bambino (One Cold and Blessed Winter)” (Apple Music, Spotify), “Mary’s Little Boy Chile (Calypso Christmas)” (Apple Music, Spotify), and the title track (Apple Music, Spotify)—which is to me the definitive version of “The Little Drummer Boy”—tied our 1980s Christmases back to the 1950s celebrations my parents remembered.

My father has always been an excellent whistler. It may have been the trumpet training. I can’t whistle worth a damn, but I took drum lessons and can hand-drum like I’m Buddy Rich—so there you go. In any case, when I think back on those Christmas mornings, I can always hear Bappo whistling along with the woodwinds on Harry Simeone’s masterful arrangement of “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” (Apple Music, Spotify). Last year the Boston Pops played it, for the first time in the ten-plus years we’ve been going. What a treat. That’s the song I’ve selected for this Monday post, which just so happens to land on Christmas Day.

I can’t (and won’t) sign off without mentioning Christmas breakfast, which my Aunt Marilyn and Uncle Bob hosted at their house every year. We were always last to arrive. The time slippage started with my Mom’s beauty routine, as earlier discussed, but was compounded by the extra time we took together at our place unwrapping presents and exchanging hugs. We were always thrilled to join the extended family for fresh waffles and strawberries on Marwood, and to pluck from a variety of Christmas cookies arranged on Aunt Marilyn’s tiered platter in her kitchen. I always especially liked the mint-flavored brownie things with the green icing. I just asked my Mom and sister what they were called—grasshopper cookies, they told me. We lost my Aunt Marilyn a month ago, so I am holding these mornings at her home especially close in my heart this year.

Then later in the evening, turkey and stuffing and Asti spumante (but not for me—where are the Cokes?) at the Abruzzi-side Grandparents’ place, just around the corner on Wainwood. This was where it always got the loudest, with dance routines from the younger cousins, screenings of home movies shot by my grandfather from the 1960s, and there’s our Zio, poised again over the VHS player, this time to queue up the Band Aid video he had recorded off of VH1. And why not let the tape keep playing, so we can watch the video for “West End Girls” (Apple Music, Spotify) as well?

Round about 10 PM—in the college years, at least—My Gang would crash the party on Wainwood. Brad, Bob, Mark, and Mark arriving to fish me out of my family time so we could go downtown to see the Februarys play. Maybe we’d veer off down Halsey Drive and pick up Sammy on the way. Alli would meet us there, and of course Tia, too. But we’ve already covered this. (See “Any Wednesday,” again.) I’m holding those times with friends close to me as well.

Traditions, traditions, traditions. Memories, memories, memories. It’s Sunday night, and I’m only just now wrapping this up. The Christmas Eve Party on Pearl Street is due to start in just under 2 hours. Time to drop the laptop and get hopping. This party isn’t going to prep itself. Quoting Clement Clarke Moore then, by way of The Chorale:

Merry Christmas to all—and to all a good night.

A tender wrap-up of our Christmases past. Way before your time, our Christmas Eves were spent one block away from our Patchen Ave home, at Uncle Buff and Aunt Vi’s on Edgehill. Around 10 -10:30, someone would say, “Are we gonna call Michigan?” A call to Aunt Elsie’s in Dearborn would quickly ensue, and we’d spend the next 15 minutes or so passing the phone around to our relatives, who were passing the phone around on their end. Traditions.

I know .. there are volumes, right?