I grew up in Northeast Ohio. I lived there for almost eighteen years, before I went back East to college, where I’ve stayed. Lately when I think about home, my mind’s eye serves up an image of cracked concrete with weeds growing through it. Consistently. And as best I can figure, this is because lately when I go back to Ohio, I’ll rent a car at Hopkins Airport and take surface roads into Cleveland, and that’s what I’ll see on the way: cracked concrete and weeds. It’s not to the point of Boston in The Last of Us, where the city is uninhabited and nature has reclaimed it. We haven’t come to that. But at any point, on any sightline when I’m making that drive into the West Side, I am penned in by markers of neglect and overgrowth.

Hence, cracked concrete and weeds.

I don’t like what my brain tells me to see when I think about home. I don’t like what it says about my home, and I don’t like what it says about me and how I think about my home. So whenever I see cracked concrete and weeds, I go to work. I try to substitute in other, more appealing images. Maybe not images, strictly speaking, because they have movement when I see them, so let’s instead call them .gifs:

.gif of lights splayed and twinkling across the Mahoning Valley, when you’re driving that bend on I-680 at night: streetlights, brake lights, headlights, lamplights, the lighted signs of businesses—all of these gathered together and burning off into the night.

.gif of green leaves rippling against the bright blue sky, as they did on so many spring days when I would lie on the grass in my yard and just look up at the trees.

.gif of my grandfather’s restaurant on a Friday night, packed to capacity—front room, back room, party room, lounge—bustling and loud, with wait staff and busboys scurrying in all directions between the tables, through clouds of cigarette smoke and bursts of laughter, and somehow not colliding.

The thing about the brain is, involuntary beats voluntary every time. You can force-substitute the memories you want for the thoughts you have, but your chosen defenders can only hold the line for so long. So when I close my eyes and try to place myself back in Ohio—back home—time and again I am greeted with cracked concrete and weeds. Overgrowth and neglect.

When Adam Smith spun up the concept of the invisible hand, he was talking specifically about the allocation of capital and the thumb That Hand puts on the scale for domestic trade. (I just looked this up: let it never be said that I don’t do research for these posts.) But by now we know that This Invisible Hand gets up to so much more mischief than that. It lifts economic focus and capital from one location and places it down in another, as it thinks is best for Overall Growth. It also moves labor toward capital, by which I mean to say it shoves people across the country and around the world, like so many pieces on a chessboard. We think we make these choices ourselves, but do we really? Somebody puts a university in New Jersey, a law school in Boston, and off we go to them. I wouldn’t expect that from up top, at the level where The Hand is operating, any of us look much different from, or are any more consequential than, lab rats, winding through a maze toward a hunk of cheese.

Used to be there was a lot of good cheese in Northeast Ohio. Cleveland, Akron, Canton, Youngstown. Shipping and manufacturing, rubber, cars, steel. There was a time when Cleveland proudly called itself “the Sixth City,” because it was in fact the sixth-most populous urban area in the United States. Ohio was a repository of opportunity, and therefore a destination—for immigrant families from Southern and Eastern Europe, for African Americans looking to leave behind Jim Crow bullshit in the rural South.

Terminal Tower, CWRU, Kent State, YSU, Goodyear, Firestone, Republic Steel, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, Higbee’s, May Company, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Playhouse Square, the Kenley Players, Cedar Point, the (then-) Cleveland Indians, the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Packard Electric, the Cleveland Clinic, University Hospital—hell, let’s even throw Abruzzi’s Café 422 into the mix. So many important institutions built up from scratch after labor met capital, a community was formed, and a region reached for the stars.

But history happens. The Hand picks winners, but winning isn’t forever. Social conditions change, technology advances, and industries diminish in importance. Other communities emerge and compete: maybe their labor is cheaper and more cooperative, maybe they throw money and subsidies in the air to attract capital, maybe they invest in infrastructure. There are a million reasons why communities prosper and decline relative to one another, and this post isn’t going to sort through them all. That work gets complicated and politically fraught and, ultimately, boring. My point is that whatever social and economic policies we might interpose to nudge it in one direction or another, The Hand giveth, and eventually it taketh away.

That second part is a real bitch. It leaves a city, a region, a state reeling and without answers. Time marches on, capital goes elsewhere, and people leave. Rats, all of us, flicked on our backsides by a merciless Olympian finger, ditching Warren for Cleveland, Cleveland for Boston, the Midwest for the Coasts, fanning out across the landscape, wondering what kind of dickhead would have moved the cheese, so that we had to leave home to find it.

And so many of us have left Ohio. We come back to visit, but you can’t go home again, you never step in the same Cuyahoga or Mahoning River … <insert applicable cliché here>. It’s an unremarkable truth of human psychology that when you revisit anything at all—an old record, a movie, a place that holds meaning for you—the delta between What You Remember and What You See Now is always jarring, particularly if it’s been a long time between visits. This is true even when you return to a place and find it thriving. When it’s not thriving and it was your home, that goddam delta is jarring and upsetting and heartbreaking.

Cracked concrete and weeds = Cuyahoga delta blues.

Chrissie Hynde grew up in Akron, and she left, too, in the early 1970s. She was on campus at Kent State when the shooting happened, and she was over it. Off to the U.K., then, where she ran with the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and Ray Davies with the Kinks, then formed a band of her own called the Pretenders. Chrissie always had Ohio on her mind. Side A, Track 1 of the Pretenders’ first, self-titled record is “Precious” (Apple Music, Spotify), is Exhibit A:

I like the way you cross the street, ’cause you’re precious. Moving through the Cleveland heat: how precious … East 55th and Euclid Avenue was real precious. Hotel Sterling coming into view: how precious.

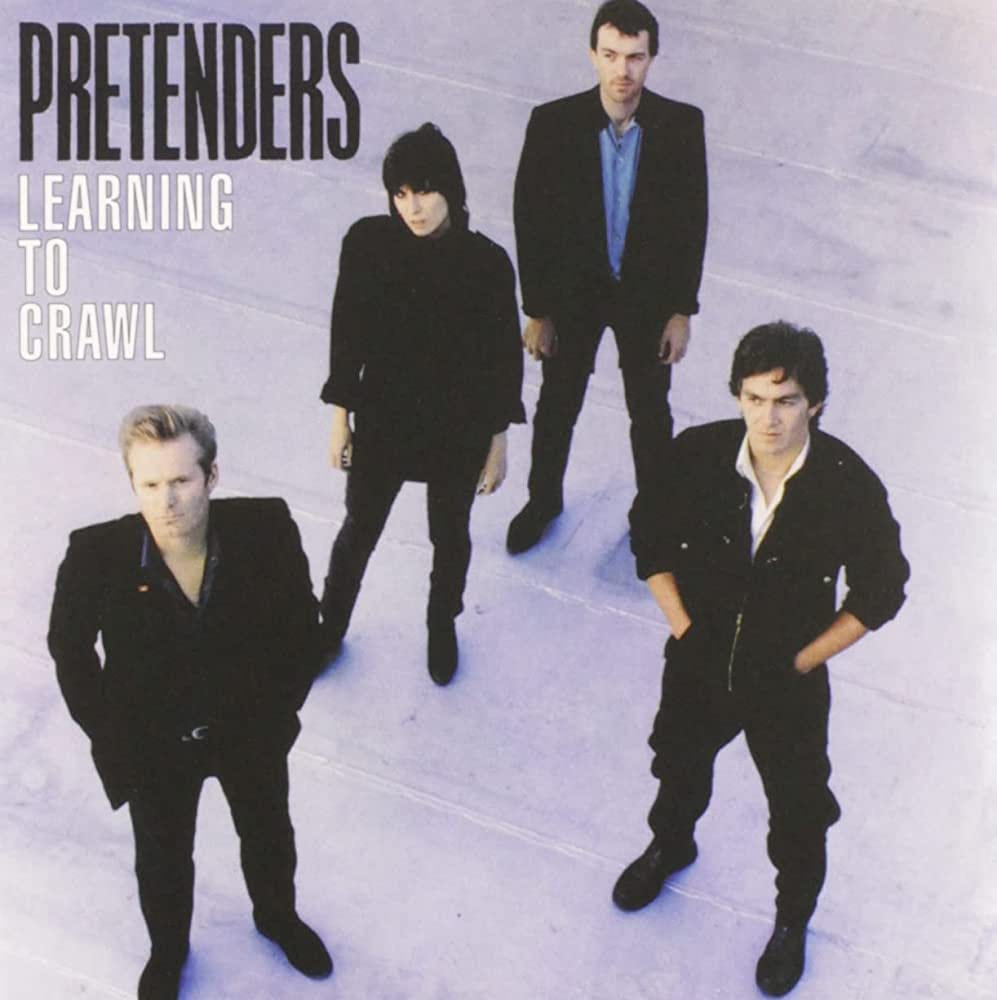

“Precious” is probably my favorite Pretenders song, but as much as I love it, the lines in it about The 216 are too oblique to get to the heart of the matter here. For that reason, I’m going instead with “My City Was Gone” (Apple Music, Spotify), from a later Pretenders record, Learning To Crawl. Chrissie’s Cuyahoga delta blues message here is clear enough:

I went back to Ohio, but my city was gone. There was no train station, there was no downtown. South Howard has disappeared—all my favorite places. My city had been pulled down, reduced to parking spaces.

Hey ho, way to go, Ohio.

I went back to Ohio, and my family was gone. I stood on the back porch: there was nobody home. I was stunned and amazed. My childhood memories slowly swirled past, like the wind through the trees.1

Hey ho, way to go, Ohio.

There were other possibilities here: R.E.M.’s “Cuyahoga” (Apple Music, Spotify), Springsteen’s “Youngstown” (Apple Music, Spotify). But I don’t need a guy from Asbury Park or Athens giving me my cues here. Chrissie Hynde is an Ohioan through and through. She feels my pain—of dislocation, disorientation, and, in the final analysis, loss—and I feel hers.

Chrissie’s inclined to hang that loss on “Ohio,” and more specifically, on the choices community leaders made after she left. My pretty countryside, she laments, had been paved down the middle by a government that had no pride.

That’s certainly a part of the problem. Build another strip mall? Sure. Frack my shale … please! There’s no high-level bargaining with The Hand, so you’re reduced to selling off scraps to keep the lights on. Short-sighted and heartbreaking, sure, but The Hand made you do it. Lesser dispensation is due to the criminals and con artists who come in from outside, promise deliverance by unspecified means, date and time TBD, in exchange for electoral votes and Senate seats.

Hey ho, way to go, Ohio.

Let’s be clear: some amount of the loss that transplanted Ohioans feel is owed to our leaving in the first place. We could have hung in and stuck it out, but we didn’t. It’s a tough look, faulting the folks who stayed behind for cashing out to developers and energy companies. We’ve all inflicted damage, just in different ways. We all share in the culpability here.

Or do we? Could the fairer reading be that there’s no fault to be assigned or apportioned here? At least not among the rats and humans down here all trying to do the best we can, but always subject to our own limitations: our biases, our venal natures, the moral and political certainties we hold as self-evident and screw you if you don’t agree, and the fact that sometimes we’re just too damn tired to keep on Defending the Land? We don’t create the conditions that wear a community down to the nub. That’s The Hand, moving money and people and hope and cheese around the world to optimize the allocation of capital—and waving the bird at you on the way out the door.

Or as Chrissie Hynde says in another of her perfect songs (Apple Music, Spotify):

The Powers That Be that force us to live like we do—they bring me to my knees, when I see what they’ve done to you.

Honest to God, I did not have this line from the song in mind, when I wrote up .gif #2. But when I typed out these lyrics just a moment ago, I felt a little closer to Chrissie Hynde, not just in how I feel about home now, but in what we saw there, when we were growing up. Pretty cool.

Beautifully written and emotionally charged depiction of our lost city. I am much older than you, I went back 2 yrs ago, it pained me and pained me even more when those who never left, defended the loss of the wonderful, vibrant town I grew up in, as being just as great now.

And yes, Abruzzi’s restaurant was a big part of what Warren was. The anniversaries, birthdays, and special occasion meals that we dressed up for and your Grandpa not only played the trumpet but made us feel like we were the most important person in the restaurant each and every time! Maybe The Hand caused the demise or maybe small minded people simply still refuse to believe that the way things were will never come back. Anything stagnant is bound to stink.

Sorry I rambled but ‘My city was gone’ brought out so many emotions of the amazing childhood I had and the sadness I felt 2 years ago.

June 7, 1911 - Warren, Ohio is the first city in the U.S. to have all of it's streets illuminated with incandescent lamps. Those lamps were manufactured in the city at the Superior Electric Co. on Summit St., right next to the Mahoningside power plant.

The city became known as "The Tungsten City" and "Lampville, U.S.A."

Warren was second, only to New York City in electric lamp production. By 1920 Warren had 20 electric lamp manufacturers and was the fastest growing city in Ohio.

So many missed opportunities from our town.....