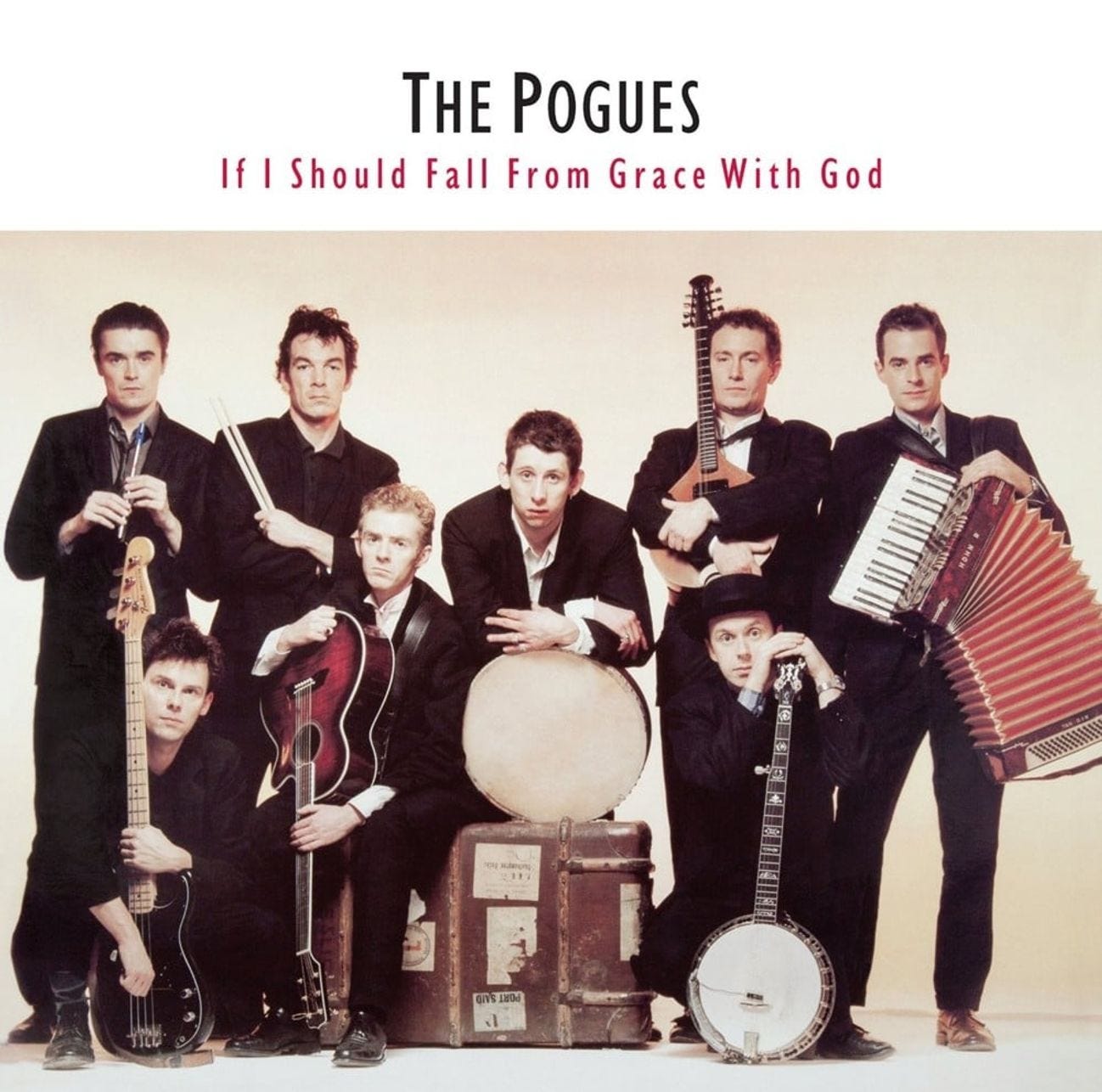

The Pogues, "If I Should Fall from Grace with God"

The old saw is these things happen in threes. They certainly did in Brazil this past year, when all of Gal Costa (Apple Music, Spotify), Rita Lee (see “Panis et Circenses”), and Astrud Gilberto (Apple Music, Spotify) left us over a period of six months. Now in July we lost Sinéad O’Connor, and just this past week Shane MacGowan.

Who’s next? you’re asking, and you’re absolutely terrified. Take heart, readers—I saw Bono just two days ago (!)—he’s in great health and feisty as ever. (More on this in another post.) No no no no no: it’s far more likely that in this particular sequence Our Dear Shane, the consummate survivor this side of Keith Himself, held out the longest and ran third.

And any number of departed musicians could round out the group for us. Paddy Moloney, chieftain of Chieftains, is the leader in Heaven’s Clubhouse, but he passed some time ago, in late 2021.1 Other, more recent deaths might as readily be joined to Sinéad and Shane’s. Anyone who loved their music surely loved the Specials, too—Terry Hall told similar stories and was a kindred spirit. Keith Levene, of Public Image Limited and briefly the Clash, was essential to the punk movement/ aesthetic that spun the Irish up in these two, even if ultimately they took their sounds in different directions.

The multiplicity of options here speaks volumes about how complex and multifaceted these two artists, Shane MacGowan and Sinéad O’Connor, really were. It was always too easy to reduce them to five-word summaries: on one hand staggering drunk, toothless, tuneless, broken; and on the other, too much, strident, hairless, damaged. But if you took the time to listen to their music, if you ever saw them on stage performing, then you know each of these two was so much more than this. And what ever should happen if they should work together?

My first impression of the Pogues centered, as expected, on Shane. He was the front-man, after all, growling and gurgling and gnashing what was left of his teeth. My takeaways from what I saw of the band’s mid-’80s MTV and Saturday Night Live appearances were Irish, played fast, rotting mouth. At that time I hadn’t tapped into punk rock, so I didn’t appreciate the dizzying singularity of what the Pogues were up to. Of course, these days Celtic folk-punk is a rock genre all its own. The Pogues blazed the trail for Black 47, Flogging Molly, Dropkick Murphys to follow—hell, you might even say Shane MacGowan drank, and drank, and fell, and bled from his head so that the Murphys could get the Key to the City of Boston decades later. But for a Midwestern kid in the mid-1980s, steeped in Duran Duran and in awe of Adam Ant, the look, feel, and sound of the Pogues wasn’t what I was looking for. At all.

Fast-forward to my college years. Shane is gone from the group, sent away because his bandmates simply couldn’t live with him anymore. Consider what this means: seven drunken rioters—and let’s be clear, that’s what they were—roust their front man, glue guy, essential spirit, and principal songwriter out of the band, because the delta between his drunken rioting and their drunken rioting had grown too vast and consequential for them to deal with. The Pogues keep their name and move on, releasing two Shane-less LPs. The first of these, Waiting for Herb, is the first Pogues album I’ll every buy.

And it’s a very good record. Its first track, “Tuesday Morning” (Apple Music, Spotify) is one of several nominees Kate and I have for our song. It played at our wedding. DJ Bart used to spin records—well, CDs—at Cedar’s in downtown Youngstown on weeknights, when I was home from school during the summer and holidays. “Tuesday Morning” was one of Bart’s favorites, and whenever he played it I’d lose track of the moment and slip into a funk. We were apart, Kate and I, and I missed her.

As much as that song is an all-timer for me, and as enjoyable as Waiting for Herb is overall, it’s watered-down Pogues. 40 proof. I didn’t spring for the strong stuff until the summer of 1998, when I was touring the UK and Ireland. The HMV in London had a discount section up front, with racks and racks of CDs priced at £9.99. If I Should Fall from Grace with God was one of those discounted albums. With the exchange rate what it was—around 1.7 USD per British pound—this wasn’t a deal at all. The problem was, the per-pound price of a CD in the UK was close enough to the per-dollar price in the US that you didn’t sweat the difference. So I bought easily a half-dozen of these “discounted” CDs, including IISFfGwG, to set spinning on my travels north and west. Crazy to think I’ve loved a band this much for 25 years, basically because I was too lazy to do the math on that June afternoon in London.

I remember exactly where I was when I first heard “Fairytale of New York” (Apple Music, Spotify). I was midway—or at least partway— through a train ride from King’s Cross to Edinburgh. I had got off the train in York, to spend a few hours walking the old medieval city, had just climbed two flights of stairs, and was walking on the top of York City Walls. I can picture in my mind’s eye exactly where I was standing—the trees off to my right, the slight leftward bend of the battlements ahead of me—when this song first played through. It sent chills down my spine. Track 4 on the CD, and I had enjoyed the first three well enough. But this here—this duet Shane sang with Kirsty MacColl, about down-and-out expatriate love in Manhattan—was something else entirely.

It was Christmas Eve, babe, in the drunk tank. An old man said to me, “Won’t see another one.” And then he sang a song: “The Rare Old Mountain Dew.” I turned my face away and dreamed about you.

As a poet and lyricist, Shane MacGowan had a great many masteries. He could put you literally anywhere on Earth—Siam, Spain, Soho, the Shannon River—and the destination would feel real to you. He had a gift for timing, too. He knew exactly when to lean into pathos, nostalgia, spitting anger, or raucous humor. Often, as in “Fairytale,” he would send you careening from one strong feeling to another, leaving you exhilarated by song’s end. And god damn could he spin a yarn—from a first, second, or third person perspective, in the form of tall tale, ghost story, urban realism … whatever would hit the hardest in a particular moment, that’s what Shane swung with.

But I want to talk here, specifically, about his mastery of character. The trick of writing characters is for them to be different (i.e., distinctive and therefore interesting) and the same (i.e., universal and therefore reachable). That’s a neat trick to pull off when you’re writing a novel, let’s say, and you’re unencumbered by rhyme, meter, or the limits of length. Try doing it in a song. Try delivering into the world this “Fairytale” couple, Shane and Kirsty, so sharply and completely, in two verses, chorus and bridge, over a crisp 4:46. We know exactly who these people are, we grasp the tragedy and comedy of their experience, and we bask in the specificity and generality of their good—no, great—story. I hope never to spend the holidays in the drunk tank, but I did spend several of them without Kate. I turned my face away and dreamed about you took me right back to DJ Bart and “Tuesday Morning.” Still does.

When a song like “Fairytale” grabs your attention, you can bet you’re going to give the rest of the record a close going-over, just to see what else you’ve been missing. Now here’s “Bottle of Smoke” (Apple Music, Spotify), in which the narrator boasts about a big win at the track—Twenty-fuckin’-five to one!—and considers how he’ll spend the money. And “Fiesta” (Apple Music, Spotify), which kindasorta chronicles the band’s time in Spain shooting scenes for Straight To Hell, Alex Cox’s indie Spaghetti (Paella?) Western. Shane sings bitterly about British justice in “Birmingham Six” (Apple Music, Spotify): for more on this, see Daniel Day-Lewis’s In the Name of the Father. The capper here is “The Broad Majestic Shannon” (Apple Music, Spotify), similar to “Fairytale” in its instrumentation, and every bit as glorious. “Shannon” also played at our wedding, per our instructions to the DJ: a fitting anthem for a couple pledging to grow old together.

Take my hand, and dry your tears, babe. Take my hand, forget your fears, babe. There’s no more pain, there’s no more sorrow. They’re all gone—gone in the years, babe.

Upon returning from the UK and Ireland, I picked up another four Pogues CDs, then two more by Shane MacGowan and the Popes, his post-expulsion project. I enjoy all of these, but the first three Pogues records, Red Roses for Me, Rum Sodomy & the Lash, and If I Should Fall from Grace with God, stand above the others.

For most of my first two years in law school I listened to the Pogues … I won’t say non-stop, but certainly more than any other band in my music collection. And as this period coincided with the Napster Window (kids, Google it), I also happen to have a ton of single tracks—non-album singles, B-sides, live recordings—loaded on this very computer in an .mp3 format. I wouldn’t expect the Pogues to fault me for looting all those songs; these depredations were undertaken in the anarchistic spirit of “The Boys from the County Hell” (Apple Music, Spotify) and “The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn” (Apple Music, Spotify), after all. As for the record companies, those miserable bollocks and bitch’s bastard’s whores weren’t making these songs available anywhere for me to buy, anyway.

Shane rejoined the Pogues for some tour dates in early 2006. They played the Orpheum in Boston right around St. Patrick’s Day. Of course I was going to be there. And of course I was going to stay for the duration of the show, notwithstanding that the band played so loud that Kate, seven months pregnant with Florian at the time, began to fear that the kid was going to have hearing damage through the soundproofing of her uterine wall and amniotic fluid. I gave her cab fare home four songs into the performance. She didn’t sweat it, but still I felt just a little bit wrong about sending her off by herself—wrong enough, at least, that this story is parked front of mind when I sit down to write about the Pogues.

A word or two now about the other band members. They were steeped in punk themselves, and they carried its ferocity forward in their folk adaptations. Yet they had the good sense, too, to blend traditional and modern sounds together in equal parts. The Pogues had the musical chops to deliver a gorgeous, multi-tracked ballad, then turn on a dime and play in a hurry. Chevron, Fearnley, Finer, Hunt, O’Riordan, Rankin, Stacy, and Woods variously on guitar, bass, drums, accordion, banjo, fiddle, and tin whistle, with harmonica, hurdy-gurdy, saxophone, congas, sitar, and horn section thrown in, from time to time, because why the hell not?

The Pogues’ oeuvre is thick and rich and bursting with life. The albums Shane did with the Popes brought much of the same vitality. It’s not hard to imagine an immersive, Second Life-style digitally simulated world constructed entirely out of MacGowan’s imagination, and filled to the brim with characters pulled from his songs—dramatis personae/ NPCs drawn from all walks of life and all corners of the world, if especially England and Ireland. Come on down to Leicester Square, where the hopeless romantic of “A Rainy Night in Soho” (Apple Music, Spotify) might flip 50p into the wet cap of a dying rent boy (Apple Music, Spotify). You and thousands more can sail across the Western Ocean (Apple Music, Spotify) to wake Big Jim Dwyer with the Tinker Boys (Apple Music, Spotify)!

All well and good, this idea I have, but Shane would never have stood for it. He did his work in the old style—with words, not bits and bytes. Even before he died, critics were calling him the last, or at least the latest, Great Irish Poet. Writing as he did with Behan and Lorca in front of mind (among others), this is the tradition that a pogoing London punk found, felt, and lived his way back to join. Like all the greats, he broke ranks and pushed forward, but always with a learned eye on the past and the treasures it bestows. And now he, too, is one of those treasures.

If we didn’t know what we do about Mr. MacGowan’s hard living, an argument could be made that his health failed because he poured out so much of himself—too much of the life that was in him—into his life’s work. Now that the vessel is empty, there’s nothing for it but for us to gulp down all that life and call, in vain, for another round.

The song I chose for today—“Fairytale” being all too easy, especially with the holidays upon us—is the title track from that record I bought at the London HMV a quarter-century ago. It’s Track 1 on the CD, and so the first song I heard as I was climbing the steps up the walls of York:

If I should fall from grace with God, where no doctor can relieve me, if I’m buried ’neath the sod, so the angels won’t receive me, let me go, boys. Let me go, boys. Let me go down in the mud where the rivers all run dry.

Bury me at sea, where no murdered ghost can haunt me. If I rock upon the waves, no corpse shall lie upon me. Coming up threes, boys. Coming up threes, boys.

Years ago, at the height of my fascination with the Pogues, I rented a VHS tape of the band playing live. In the video Joe Strummer gives an interview, and he raves about this Coming up threes line:

When I get a group together I’m definitely gonna cover “If I Should Fall from Grace with God,” because playing that number in America, I have to restrain myself from rushing on-stage. It’s not the playing of it I want to join in on, it’s the singing of it, you know? Coming up threes, boys. Coming up threes, boys …

Fine, Joe, but what does it mean? Just now I went to look, and I found a Google Groups post where a user asks the same question. In the discussion that follows, certainty is elusive, but possibilities abound. The phrase could refer to a string of bad luck: i.e., repeated throws of three in a craps game. Or it’s describing the phenomenon whereby a dead body, thrown into the sea, rises three times before sinking—at least, according to legend. It’s suggested, too, that Shane might be misheard here, and he’s in fact singing the words coming up trees: feeding the trees, pushing up daisies. Finally, one of the contributors suggests that “deaths come in threes.”

I’m writing this on the flight east from Vegas, where I played craps (badly) last night. I sat down in this seat a few hours ago, opened a new post page and started with the words these things happen in threes. Now, improbably, I’ve wound my way back around to that first proposition, and the pilot has just announced we’re beginning our final descent.

Rest in peace, Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan. Your river never ran dry.

It’s widely believed Paddy died of a broken heart—that the cancelation of so many performances because of COVID-19 sapped him of his will to live. For sure, we had tickets to see the Chieftains in Boston in March 2020.

Your post is always great timing. I love this break from analyzing collateral packages and calling title companies on errors. And another great read.

I got out to our company Christmas party on Saturday, main event was The Chainsmokers, pretty good and had 6,000 Mortgage employees engaged.

Looking forward to next weeks!