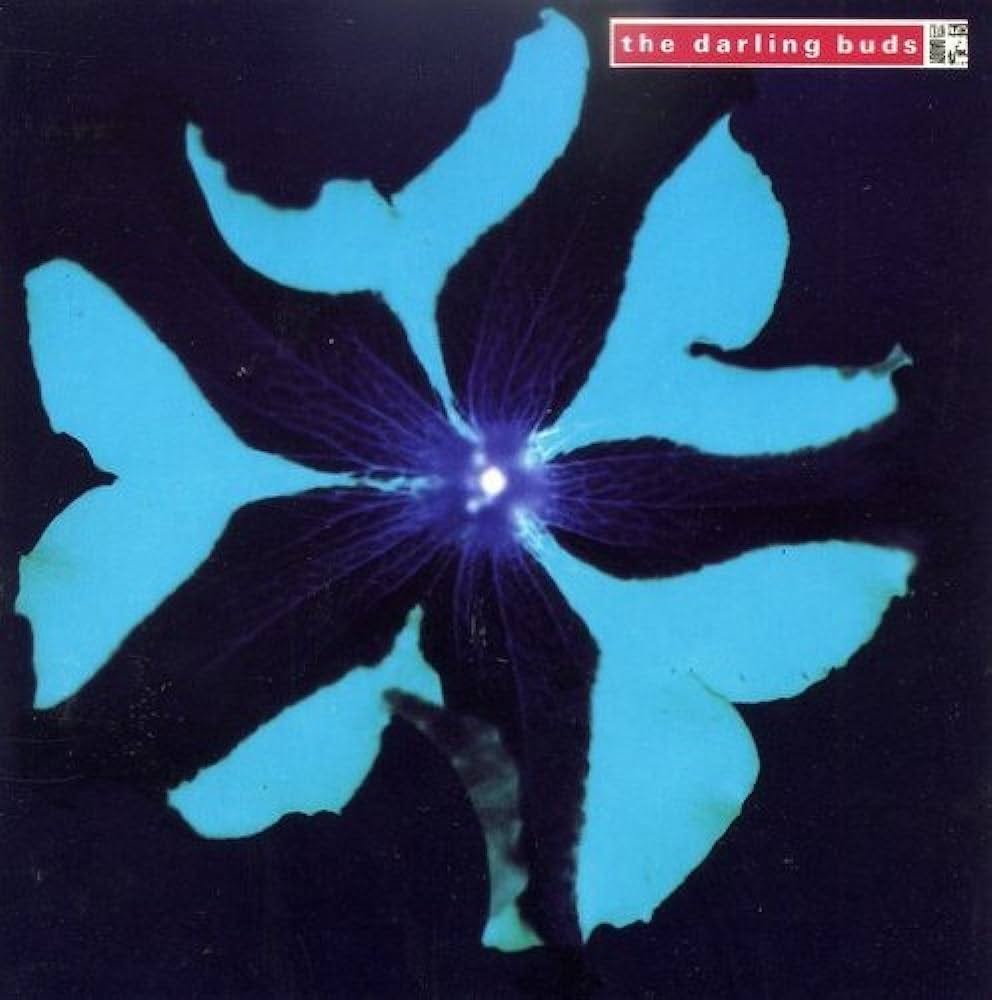

The Darling Buds, "The End of the Beginning"

This weekend my older child, Florian, graduated from high school. Well, strictly speaking he “walked” earlier today, in a custom one-off commencement ceremony that his principal was generous enough to offer our family. Turns out every year the state ultimate frisbee tournament is held in Western Mass. on the same day that Belmont High School holds its graduation exercises. As captain of the top-seeded team in Division 2, he opted for one last hurrah on the field, slinging a disc instead of a mortarboard. He did a family dinner Friday night, played in the tournament on Saturday, and got his diploma from Mr. O’Brien Monday morning.

With all this happening, plus the college applications, visits, and decisions preceding it, I’ve been taking time to think back on my own senior year. It’s a strategy I use to keep from being overcome by the current moment, and the savage acceleration of time that carried me here. When my knees are about to give out, I reflect on my last dance with Howland High School.

1990-1991 was a different kind of academic year for me. I had banked some high school credits in 8th grade—enough that four years later the administration allowed me to skip the first three periods of school each day, provided I could show I was enrolled in an early morning course down the road at Youngstown State University.

In the mornings I got up, showered, and drove off down Route 11 in my apple-red 1989 Chevy Blazer to the Belmont Avenue exit, then cut across town toward the University for an 8 AM start time. I checked in and out of the lectures without speaking to any of the other students. Headphones on, volume maxed out, eyes on my shoes. I felt like it was obvious I was too young to be there, and I didn’t especially want to be seen. Kind of silly, in retrospect, to think my Poli Sci and Intro to Philosophy classmates were aware of the fact I was one or two years younger than they were. But when you’re in high school, even—and maybe especially—as a senior, the gap between your stage of life and a college student’s feels all but insuperable, at least in part because it’s out there just ahead of you and is downright terrifying.

Pulling into the Howland High parking lot at 10:20 AM was a different story. My two best friends Mark and Brad1 sat together by the window of Mr. Potashnik’s classroom, which fronted on my walk in from the parking lot. Without fail they were turned toward the window to greet me as I passed by toward the school doors. They would wave, flash hand signals, occasionally even shout to me, and on first sight of them I instantly felt like a part of something again, after a morning spent in abstraction while in class at YSU and in solitude during the commute.

My college classes didn’t meet every day, so at least once a week I was able to sleep late, roll out of bed around 10 AM, and still get to school in time for fourth period. Somehow word got to my German teacher Frau Hrabowy that I had these mornings free. There was no more German for me to take, because I’d completed German IV as a junior, after starting German I in eighth grade: one of those banked credits I mentioned earlier. Maybe the Frau (as we called her) missed having me in class—or maybe she just saw an opportunity—but sometime in the fall of 1990 she decided she and I would both be better served if on my day off from YSU each week I reported to her classroom and graded papers for her.

So it was that every Thursday morning—or was it Tuesday?—the phone would ring four times, I’d roll over in bed as the answering machine clicked on in my parent’s bedroom, and from across the hall I’d hear the Frau calling out:

Richard! (Pronounced REE-kard, this was my assigned German name.) Are you sleeping? Wake up, Richard! You are needed at school! And so on. At all other times Frau Hrabowy and her Austrian accent were adorable—just not so much on these mornings.

Even on the days when I had class in Youngstown, I had enough time each day to drive back to Springwood Trace and hang for 30 or 40 minutes at home before dropping in on the high school. I treasured this quiet time. But I shouldn’t call it quiet time: usually I was down in the basement, shooting pool with the stereo playing at levels my parents wouldn’t have tolerated if they were home. Around that time of day the sun had an angle on the basement windows and fired gorgeous shafts of light into the room. On the day in mid-March when I got my college acceptance letter, I was able to receive and open it during this grace period at home. With the verdict in hand, I set the Stone Roses to play on repeat:

This is the one. This is the one. This is the one—this is the one I’ve waited for. (Apple Music, Spotify)

Hopeless with girls, I swore off going to my senior prom. A couple of the girls who had earlier dated and dumped me (presumably for good reason) sent word through proxies that they were available. I was too proud to accept that kind of charity. It turned out the Februarys were playing downtown on prom night, so a handful of us went to the Penguin Pub to see them. (See “Any Wednesday.”) We were underage, but my influential sister got us through the door. Problem was that show wouldn’t finish until 2 AM, which was well past curfew for me. I called home from a pay phone, and I told Dick and Jeanine I was down the road at Hans’s house waiting for our prom-going friends to get back, so we could, um, ask them how it went. The live music and crowd noise in the background made this a most implausible lie. Even so, they said I could stay out. Maybe they understood I needed a night away.

I had Sean with me that night. We had become friends a year or two earlier, at our mutual friend Chris’s birthday party. We talked for hours that night by the fire pit in Chris’s backyard. Another of the invitees, Dennis Kirsch, had sworn that he could “beat the motion sensors” Chris’s family had installed behind their house. Dennis’ challenge was to cross the yard from where we sat by the fire to Chris’s back porch, without the lights coming on. Deep into the night Sean and I were talking about life, the universe, and everything. From time to time we cast our eyes over in the direction of the lump on the lawn that was Dennis, taking note that he’d advanced five yards further from when we’d last looked. Then when we were really in the middle of something, the porch lights would flash on, and Dennis would spring up from the grass, curse out loud, and walk back to the starting line.

Dennis died of cancer last year. I didn’t know him very well, but any friend of Chris and Sean’s has high marks in my book. And I specifically remember him wearing Jane’s Addiction T-shirts in the halls of Howland High, four years at least before I understood how amazing that band was. Here’s to you, Dennis Kirsch.

There were maybe eight to ten of us in our gang back in those days, all of whom mean the world to me today, because we were in the shit together. Those days were full of microdramas, tiffs, and petty betrayals, all of which carried the weight of Shakespearean tragedy at the time … and Act V stuff at that. Whenever I couldn’t take it anymore, Sean was always the one standing by to listen and empathize. We’d drive for hours on end in my car, talking through the many indignities and injustices of being teenage boys in the Midwest. I’m not sure where the others were when the clock struck midnight on January 1, 1991, but Sean and I were in my car, lamenting the fact that we had nothing to do and nowhere to go. Happy frickin’ New Year, Sean. Yeah, right: Happy New Year. Pfft. I think our plan was to ride around town looking for signs of a house party we could crash. But our classmates were always steps ahead of us. Not only did they not affirmatively invite us to these events—they practiced a strict code of silence re what was happening, where, and when.

All this to say it made perfect sense that Sean and I rode out to Youngstown together instead of going to prom.

There are a million more stories I could tell about this year, and I’ve already told some of them. Often as not, though, when I want to remember not what happened senior year but what it felt like, I put myself on Route 11 on a weekday winter morning, driving back from YSU, with the sun sparking and chipping off the snow and ice. And I’m listening to the Darling Buds.

My car’s front console had an open shelf that ran from the steering column to the passenger’s side door. It had enough of a lip on it that the cassettes I had skating around on that shelf didn’t spill out on the floor every time I hit the gas. Still, it happened often enough that I was constantly bent over the shotgun seat at red lights, grasping at a tape just out of arm’s reach, when I wanted to change the music in my cassette player. At any given time I had a dozen or more C90s in the car, usually with a full album dubbed on each side. Sonys and Maxells and TDKs. One of those cassettes had the Darling Buds’ Crawdaddy on one side and Cake by the Trash Can Sinatras on the other. That tape was as much a part of the soundtrack of my senior year as any of my hallowed Smiths records or the Stone Roses album.

The Darling Buds had a lot going for them in 1990, including but not limited to:

They were British (which counted for a lot in those days);

They had a lovely and charismatic singer in Andrea Lewis (also very important); and

They had great pop hooks.

I just read online that the band took its name from The Darling Buds of May, a novel by H.E. Bates, and not the celebrated sonnet by Shakespeare that actually coined the phrase. I don’t love this—it reminds me of the time I played the Subways’ cover of “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away” (Apple Music, Spotify) for a friend and he said he always loved the Pearl Jam original. Come on.

Anyway, my sister turned me on to them. Taking recommendations from Tia was a new development, because she’d always had more pop-oriented tastes. But around this time the Samantha Fox posters were coming down from her bedroom walls, and she’d just bought a leather jacket. I don’t know where she found the Darling Buds, but at some point right after Crawdaddy came out, she pulled me aside and played “It Makes No Difference” (Apple Music, Spotify) for me. Yeah, okay. It was good enough—actually, it was excellent—but it didn’t have those funky Mancunian beats I was especially craving at the time.

At some later date Tia had the record on and I heard “A Little Bit of Heaven” (Apple Music, Spotify). That did it: “Heaven” did bring those dropped snare strokes I was playing on my drums, and it had some great chucking wah-wah guitars on it, too. Somebody at Epic must have thought the Darling Buds had the chance to make it big, because not only was Crawdaddy well stocked in the largely desolate racks of the Musicland and National Record Mart at the Eastwood Mall, but the price point in both stores was $7.99 for the compact disc. Naturally all of us bought a copy of it right away.

It wasn’t the trendiest sound. Straight-up pop-punk rockers like “Do You Have To Break My Heart?” (Apple Music, Spotify) and “Honeysuckle” (Apple Music, Spotify) were riding the coattails of the Primitives and Transvision Vamp. I read just now that these three bands formed the core of a mid-’80s “blonde pop” scene in Britain that was swiftly rolled over and left in the dust by the Madchester scene up North.2 Adapt or die, as they say, and in several of Crawdaddy’s tracks you can see the Buds making a modest effort to shoehorn psych and dance elements into the mix. “A Little Bit of Heaven,” obviously, and “Crystal Clear” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Tiny Machine” (Apple Music, Spotify), too. But never so much as to be super-obvious about it, or to lose sight of who they were.

With the Buds and the Sinatras playing round and round in my car, on the regular, I quickly came to love each and every song on the Crawdaddy record, whatever scene or sound a given track might seem to be leaning toward or away from. Perfectly crafted and tuneful, these songs, and fun to sing along to—most especially because the lyrical themes were right in the wheelhouse of the vulnerable and shy teenage boy.

My future doesn’t seem bright. I can’t eat, can’t sleep tonight. Do you have to break my heart? If I could, I’d turn back the time. Close my eyes, pretend you were mine. Do you have to break my heart—again and again and again?

I see people in the distance. But they don’t know of my existence. If I could step in someone else and change the way that I feel … ’cause I’ve been thinking, and sometimes I might wonder why. But you won’t make me die. (Apple Music, Spotify)

On those morning drives to Youngstown and back, I didn’t have Sean around to unburden myself to. Shouting out lines from Darling Buds songs would have to suffice, and most of the time it did.

As between the LPs on either side of that dubbed cassette, over the decades I’ve certainly played the Trash Can Sinatras’ Cake more than Crawdaddy. But that’s not to say, either, that I haven’t carried the Darling Buds down through the years. I certainly had them in front of mind 18 years ago, in the wee hours of the morning when I had Florian tucked under my arm, first feeding him his bottle and then rocking him to sleep. One of the songs I would sing to him in the soft light of the butterfly lamp in his nursery was “Fall” (Apple Music, Spotify):

Love you like I wanna love you, wrap you up in cotton wool. Every thing you see—you’ll have it all. And if you every should break down, desperately going down: I’ll be there to catch you when you fall.

Going forward from today, likely as not Florian will be the one catching me.

Any of the Crawdaddy songs I’ve listed thus far—and I’ve hit almost all of them—could have served for this week. Funny enough, though: there’s a song on the record called “The End of the Beginning” (Apple Music, Spotify), and I can’t think of a better title for this post.

Already much discussed in this Substack, these two. See, e.g., “Radioland,” “2 am,” “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas,” “Always Ascending,” “I Know It’s Over.”

For more on Madchester, see “One Million Billionth of a Millisecond on a Sunday Morning.”