Two weeks ago I wrote about the exceptional and eye-opening performance Gogol Bordello delivered as the Dresden Dolls’ primary opener, back on November 1. (See “Mishto.”) At some point early in the set—maybe a handful of songs deep—I texted several friends and said, Unless the Dolls do something drastic later, I’m kinda thinking this is the Gogol Bordello show.

Lawyers write qualifying clauses for all sorts of specific reasons, every one of which derives from the same general rule, which is You never know what could happen. And let’s just say that 90 minutes later, the Dolls did reclaim their sovereign sway over the night’s bill. Theirs was a very different vibe from Gogol Bordello’s, starting with the fact that it was just the two of them on stage: Amanda Palmer on vox and keys and Brian Viglione on drums and very occasionally acoustic guitar. Amanda’s setup consisted of a Kurzweil piano with custom mods amending the logo so it read KURTWEILL (haha). Brian was piloting what looked like a five-piece kit, but with two floor toms. Do I have that right? [goes online to check …] Yes, confirmed.

The two of them are spectacularly gifted and accomplished performers. Now adverbs of degree are a writer’s crutch, and I’m as guilty as anyone of using them. But I want to be clear: in this particular moment I didn’t mean spectacularly to mean very or exceedingly or extraordinarily or superlatively—I chose the word because in fact the Dolls’ performance leans heavily into spectacle. Hence their capacity to wrest an evening out of the greedy clutches of Gogol Bordello.

I always wonder at a drummer who can uncoil like Brian does, for hours on end, without (apparently) missing a single stroke. His aim is forever true, and he fires from a distance—a hurricane of arms spinning off precision bolts of lightning into drum heads and cymbals. The kit is masterfully miked, and the songs are self-evidently composed and arranged to foreground and feature his play. I.e., there are no rutted motorik rhythms here.1 Every bar supplies an opportunity for variation, and it seems every one of Amanda’s sung lines earns a retort or punctuation from his kit. Brian stands and sits, grabs cymbals, chucks his sticks, then pulls from nowhere another pair. Through all of this choreography he drums with authority and precision.

Likewise with Amanda on the piano. I’d say her play is effortless, except that the style of the Dolls’ music so often calls for maximum effort. The point is, she makes it look easy. She has a bench, but much like Brian’s drum stool it’s as much a launching pad as it is a seat. For considerable stretches of time Amanda will play from a half-crouch, I suppose because it affords her greater leverage to hammer at the keys. She flicks her wrists like the torsion springs of mousetraps. This is impressive work, especially when you consider the 1000+ new wave and industrial acts that tried so hard in the ’80s and ’90s to play bad-ass rock keyboards, yet never cracked the code. On his Downward Spiral tour Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor put several of his decks on swivels so he could swat them angrily out of his way before a drum break. They would swing out on their pivots and rebound back into place for him to play again. No such gimmickry here—and none is needed.

There was a dry ice effect running steadily through the show. The vapor no doubt enhances the Gothic cabaret aspect, but there came a point where I wondered if its primary purpose was to keep these two cool, given how hard they were working.

I could go on about the spectacle of a live Dolls show—or at least the one I have ever seen—but spectacle is only one essential element. The other is sentiment, and it is in this respect where the Dresden Dolls break meaningfully from the German cabaret tradition. The sentiment comes principally from Amanda, who has the advantage of owning the speaking role. Like Teller to Penn and Lowe to Tennant, Brian acts as a largely silent partner, but unlike these two he has—and takes—opportunities to express himself physically, which the mime paint on his face gives him license to do. Still, it is Amanda who sings the songs and speaks to the crowd at shows. And as I listened to her discharge these duties at the Roadrunner on November 1, I came to see that it is her honesty that makes the Dolls so very special as a live act. Because for all the stylistic indulgences embedded in the duo’s high concept, her prime directive at any given moment is to tell us who she is.

So much might be discerned from her song lyrics alone. So you go ahead and talk about your bad day. I want all the details of the pain and misery that you are inflicting on the others. I consider them my sisters and I want their numbers. Read these lines off liner notes or a web page, and you might have a notion that this isn’t songwriting by proxy or speculation. It seems personal. Then you hear the lyrics sung—on record, sure, but good God: live?—and you’re fully affirmed in your view what we have here is firsthand feeling, laid bare for all of us to examine and consider. I don’t think it is a stretch to say that the Dolls’ process of composition is to tap into the deepest well of the soul, extract its blackest and stickiest crude, and refine it into musical rocket fuel.

The effect of this work is to create real disclosure art: songs that confess, are revealing, and show vulnerability. This doesn’t sound exceptional, but in the context of, I dunno, the last hundred years?—really, it is. At bottom, art is communication, in that it necessarily consists of some form of messaging from the artist to their audience. But we know, too, that communication is not always genuine, and often as not it fails to establish any meaningful connection or rapport between the speaker and listener. This is an ongoing human failure that dates at least as far back as the moment some super-insightful antique bard was motivated to sit down and write the Tower of Babel story.

Art in particular can be oblique, alienating, off-putting. Its effect—perhaps even its purpose—may be to establish or increase distance from the artist. And for some time now this has seemed to be the very point of art, or at least art that any of us find sophisticated enough to make claims on our attention. In this respect art reflects life: modernity predisposes us to regard each other warily, across gulfs of difference and gaps in understanding. Yet a song like “Good Day” (Apple Music, Spotify), which I quoted in the last paragraph and which opened the Dolls’ set in Boston two weeks ago, invites us to consider our shared humanity with the singer—notwithstanding the cabaret style she has chosen that, certainly in its Weimar heyday, lifted the songstress miles above her admirers on the club floor.

The elevated stage was always an innovation rooted in practicality. It aimed to solve a problem of geometry: How do we give working sight lines to the people in the back? But it is a metaphor, too—and never so telling and apt as in the rock context. Rock stars exist at a level above ours. They appear from nowhere, hand down art to us, then withdraw. At no point in the process do their shoes touch the beer-sticky venue floor. Cued by my sister, who is lately digging deep into the Gallagher Brothers’ various misadventures—here’s Liam making himself tea; here’s Oasis taunting Blur at the Brit awards—I was just downstairs playing “Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” (Apple Music, Spotify) on the drums. Side A, Track 1 of the first Oasis record, whereon Liam crowns himself king and invites the rest of us to eat shit. You’re not down with who I am. Look at me now: you’re all in my hand tonight. That’s one obvious example of a rock song that puts the audience at a distance, but I also wrote a good 3000 words earlier about the sphinx-y lyrics Michael Stipe wrote to keep us all at bay. See “You Are the Everything/ “Swan Swan H.”

By contrast, here’s Amanda Palmer not only penning songs that lay it all on the line, but also taking time at her live shows, VH1 Storytellers-style, to explain to the crowd where they came from. Oh, for sure, there may be some stage trickery involved. She may just need to take a breath and cool down from the last barnburner of a number she and Brian just served up. And maybe an obscure upcoming proper noun warrants explanation: e.g., Whakanewha is a nature preserve near Auckland and one of her regular haunts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Amanda, her husband, and her son were traveling in New Zealand when its government announced a nationwide lockdown. For two years Amanda stayed put on the other side of the world from home; her husband did not. “Whakanewha” (Apple Music, Spotify) describes the collapse and dissolution of their marriage.

A fair number of the audience members might have been aware of this history. I wasn’t. Over dinner before the show I commented to friends that she was married to Neil Gaiman, only to check Wikipedia and find that this information was outdated. Amanda didn’t need to supply this back story for us, but she did nevertheless, and her performance was all the more powerful for it. Heart reaches out through song to other hearts. Strutting Liam would be appalled; Michael might have ducked down behind the bar.

Another new song—from 2022, anyway—was holiday-themed. Amanda described how she wrote it driving home alone from a prison in upstate New York, where she’d recently attended a restorative justice retreat. This song was at least one remove from autobiographical. There are no lyrics available online for me to consult, but I recall that it was sung from the perspective of a woman with a loved one (a partner? a son?) under lock and key. Leaking in around the edges of this backdrop was Amanda’s divorce and its attendant sadness. As she and Brian performed this song, it was hard not to feel her pain most acutely—or what is more important and to the point, to feel my own pain, both for the relatively few losses I’ve suffered to date and for the many that are forthcoming and unendurable, even from a distance.

All this is prelude to some further notions the Dolls put into my head at the show three Fridays ago, and that I want to explore a bit more before I wrap up this post. These are about Boston and, specifically, whether I might ever bring myself to describe it as home. But before that heel-turn, here’s a live clip of Dresden Dolls that I think epitomizes the combination of spectacle and sentiment I’ve tried so hard to describe with written text. On a first look, the balance of elements here might tip in favor of spectacle—but if that’s your conclusion I would urge you really to dig into what Amanda is expressing here.

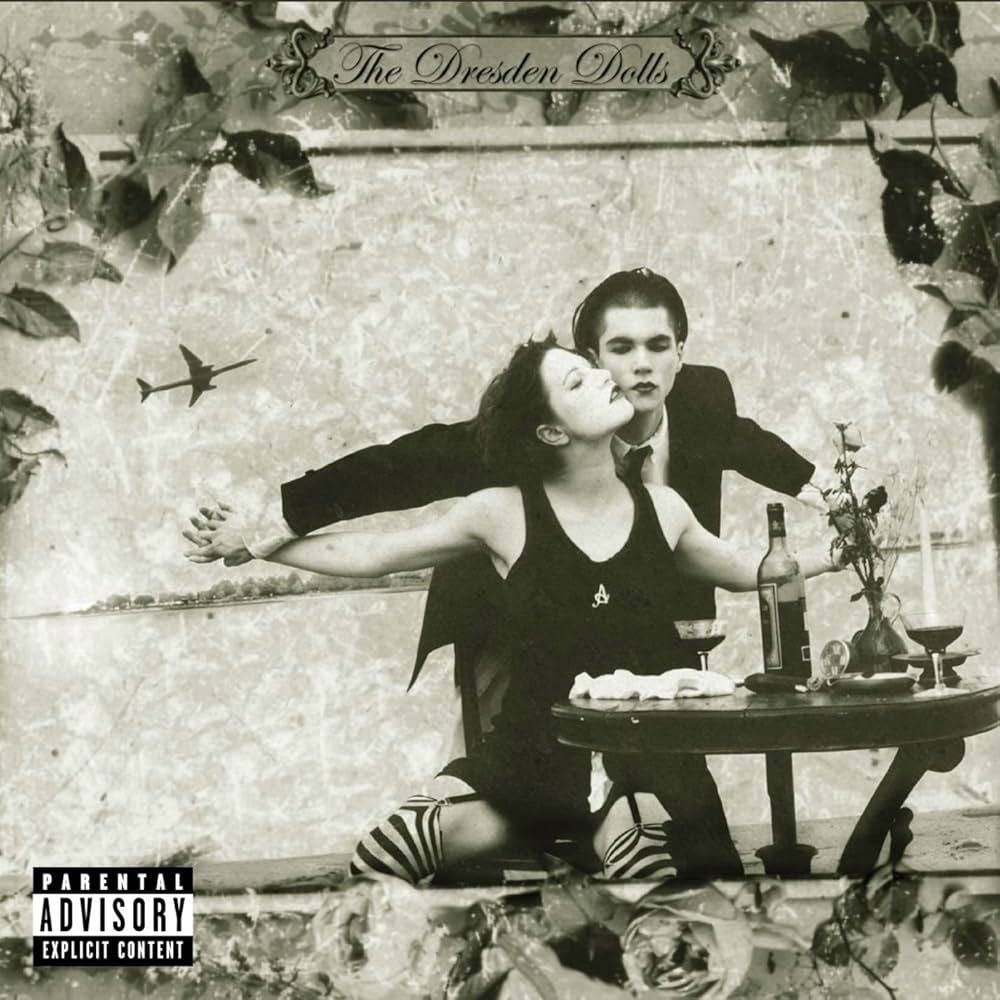

Now about Boston. The Dolls are a Boston band, through and through. They met in town (at a Halloween party Amanda hosted in 2000, we were told), burst onto the scene in the early oughts, and when the Hub couldn’t contain them anymore, they lit out to Brooklyn to record the first, self-titled record. Amanda told the gathered crowd at Roadrunner that at the time, she couldn’t wait to get free of the smothering Boston scene. Two decades later, she has moved back home and by her accounting couldn’t be happier for it. On the heels of this representation the Dresden Dolls played a “Boston trilogy” consisting of Palmer solo composition “Massachusetts Avenue” (Apple Music, Spotify) and the Dolls’ “Boston” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Half Jack” (Apple Music, Spotify).

As these songs played I took some time to reconsider my relationship to this city, where I’ve lived for 26 years now. I earlier wrote about The Sports Problem, about how essential Cleveland baseball and Ohio State football are to my identity (see “Hang on Sloopy”)—as cringey as it is to see those words in typed out in black and white—and how alienating it is to watch Sox and Pats and Bruins and Celtics fans who spend their days shivving each other in the ribs over parking spots come together on the regular as a unitary body, to lap up their championships. As I write this paragraph the Cleveland Cavaliers are closing out their 15th straight win to start the season. Will they crap out in the Garden Tuesday night against the Celtics? It’s a virtual certainty they will. But of course sports bitterness is just one aspect of my complex relationship to this city. By contrast, I feel a true affinity to Boston—very nearly ready to declare myself Bostonian—when I think of the music scene here.

Because let’s be clear: as far as rock history is concerned, Boston takes a back seat maybe to Manchester, and that’s about it. On Halloween night—the night before the Dolls show—my friend Joe texted a handful of us to say he’d been catching up on our Mixtape Diaries podcast, citing “Stand in the Place Where You Live” (Apple Podcasts, Spotify) as the particular episode he had on at the moment. I was back in my New York hotel room after dinner, and I cued up the episode to listen for myself. It has been more than three years since we laid this one down to tape. My zeal for Boston music was a running joke through the show. Each of the three us were tasked with picking and discussing three songs from musicians with ties to where we were presently living. I couldn’t help but horn in on my co-hosts’ presentations to call out their songs’ connections with Boston.

When it was finally my turn, I reeled off an exhausting-but-not-exhaustive list of Boston-area artists I wouldn’t be covering—including the Dresden Dolls. Playing the episode back on Halloween night I realized that, in stark contrast to my feelings toward the Red Sox or Celtics, I was proud of my city’s rock contributions. Proud enough even to call Boston my city, which is a phrase I would typically guard against ever letting slip out of my mouth. I should say that the songs I chose were the Modern Lovers’ “Roadrunner” (Apple Music, Spotify)—notably the eponym of the venue where the Dresden Dolls played last week—the Cars’ “Since You’re Gone” (Apple Music, Spotify), and “Not Too Soon” (Apple Music, Spotify) by Throwing Muses.

So. Many. Bands.

A completist would start with 1970s hard rock acts like Aerosmith and Boston, but I’m going to pull a Bartleby here and say, I would prefer not to. Still, the aforementioned Modern Lovers and Cars, along with the J. Geils Band, were Hub acts that festooned Rock’s Greatest Decade with their wry sensibilities and sweet pop hooks. (More than once I’ve seen Peter Wolf out and about in Harvard Square, but I’m always too slow on the draw with my phone to get a “Freeze-Frame” (Apple Music, Spotify) of him.) The early 1980s brought Mission of Burma and ’Til Tuesday. Can we take a moment to celebrate “That’s When I Reach for My Revolver?” (Apple Music, Spotify)?

Then came the 4AD acts—the Pixies, Throwing Muses, the Breeders, and Belly—who, recognizing they were partly responsible for inspiring 1990s grunge rock, did important ongoing work to deliver so many of us dissenters from its grip. I’ve written earlier about Tanya Donelly and Belly’s ringing, off-kilter Americana (see “Human Child”); in that same post I celebrated Tanya’s prior work with step-sister Kristen Hersh in the Muses. A decade ago I was fortunate to see a reformed Throwing Muses play the Sinclair in Cambridge. I don’t ever miss a Belly gig in town. Last time they played the Paradise, and Tanya made sure to tell her hometowners that we were the first to hear the new songs, aside from the neighbors she and the band had been subjecting to the rehearsals. Dunno what Mike and Glenn felt about this, but I thought first that Belly bestowed an honor on us, then second and swiftly, that we deserved this. We’re parked in the northeast corner of the Eastern time zone, and we live through 4 PM sunsets for months on end. We get new Belly first.

This is not to mention the Blake Babies, Juliana Hatfield’s solo work, the Lemonheads, Letters to Cleo, Morphine (see “Buena”), Galaxie 500 leading to Luna, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Dropkick Murphys, and the Sheila Divine. An August 2020 Boston Globe write-up looked into how it was that Boston sprung all this talent on the rockosphere. Reasonable rents and the Berklee College of Music attracted musicians to the city (though I would suggest that the area’s glut of universities played a role, too). They posted ads in The Boston Phoenix—BAND SEEKING DRUMMER, and so on—and when connections were forged and the chemistry worked, the Phoenix boosted the resulting bands’ prospects with its coverage of the scene. WBCN was a key player, too, not just for its influence, but for its willingness to air and showcase local talent.

I named a ton of accomplished and terrific acts here, and as varied as they are in their aims, sound, and thematic approach—compare the Dresden Dolls to the Bosstones, the Breeders to Galaxie 500—they all carry a similar Boston imprint in their DNA. Arty, intellectual, with a dash (sometimes more than dash) of dogmatic stubbornness and an underlying ferocity. That’s a uniquely Boston formula—just what you get when you come of age and create in a city founded by Puritans, shot up by Redcoats, settled by WASPs, unsettled by Irish (and some Italians), desegegrated by court order, colonized by hippies, and teeming today with pyschotic drivers, grad students, and torqued-up hockey fans.

Welcome back, Amanda. Now let’s fucking rawk.

Not that I harbor any grudges against motorik rhythms. See “Neuschnee.”

This was such a compelling read! I'm aware of the name Amanda Palmer but honestly she and the Dresden Dolls are an enormous blind spot for me.